When the first trailer dropped for Bohemian Rhapsody, there was much ado about its supposed “straight-washing” of Freddie Mercury, the late, legendary queer lead singer of Queen. The marketing team followed up rather quickly with a trailer that showed some glances and arm grazing between Freddie Mercury and other men. It’s the kind of passable moment that straight audiences wouldn’t take offense at and gay viewers could feel like they had some semblance of representation.

Queen has always been readily accepted by straight audiences, and Mercury is a byproduct of that acceptance. The band’s music is great, often mimicked and performed at karaoke bars all around the world, and their lead singer was an unstoppable charismatic force. Mercury took camp culture and costumes put them on stage for millions to see and revel in, that ornate persona becoming a recognizable part of him and his artistry.

“Queen made music that appealed to everyone, no matter who you were,” star Rami Malek said before the screening. But does a film like Bohemian Rhapsody, which claims to iconize the story of Freddie Mercury and Queen, help or hurt the way audiences view Mercury? And is the goal of a queer icon to make art that anyone can identify with, or should we expect our icons to openly embrace the lives they led?

However much people like to lump an individual’s private life and their public persona together, to break down Freddie Mercury, we have to explore them as separate, just as he would have preferred. “I change when I walk out on stage. I totally transform into this ‘ultimate showman,’” he is quoted saying in Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. “I say that because that’s what I must be. I can’t be second best, I would rather give up. I know I have to strut. I know I have to hold the mic stand a certain way. And I love it.”

Writer Lesley-Ann Jones captures a very intimate moment in her opening of Mercury, one in which he explains the monster he’s created and the struggle of this dual persona: “Of course it’s a drug, a stimulant. But it gets tough when people spot me in the street, and want him up there. The big Freddie. I’m not him, I’m quieter than that. You try to separate your private life from the public performer, because it’s a schizophrenic existence. I guess that’s the price I pay.”

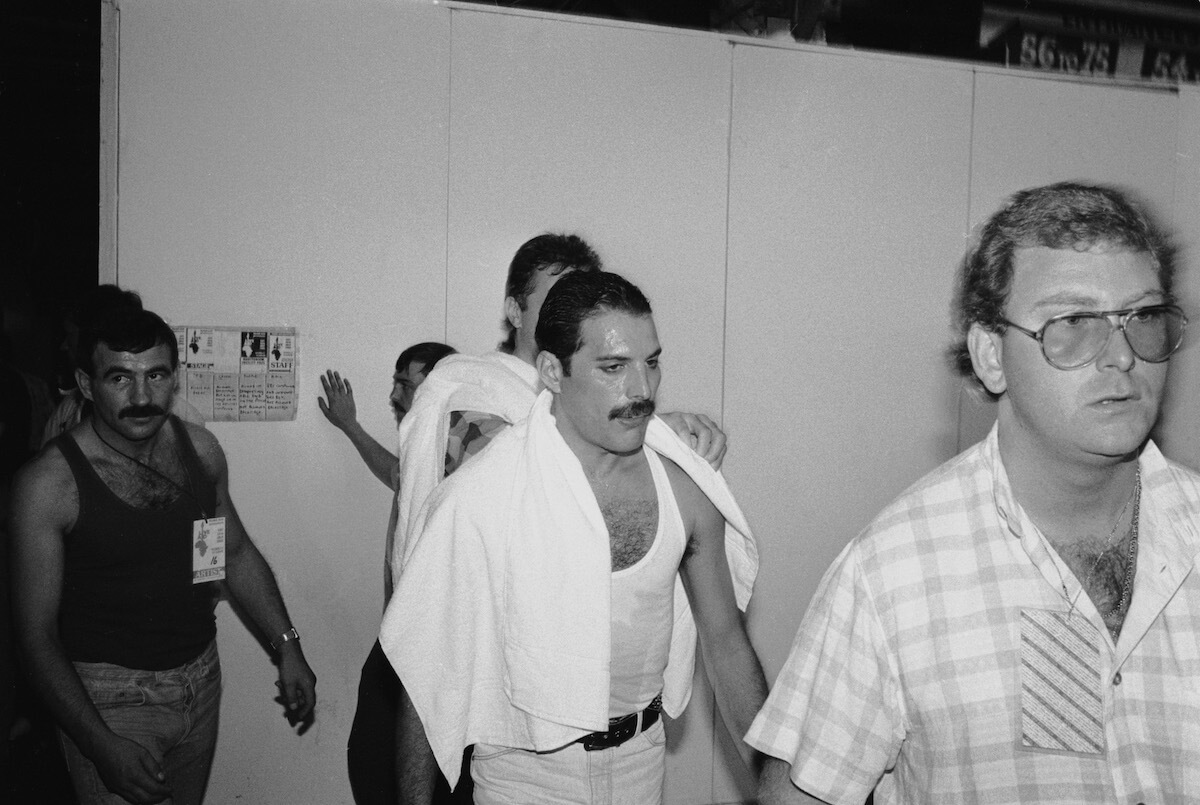

Freddie Mercury would never come out officially in his life, but he certainly lived his life as though openly queer; his friends all knew about his sexuality, there are more than enough pictures of him with men and women, and there’s even speculation as to how he slipped it into Queen’s music. Tim Rice, co-creator of Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita, as well as a collaborator of Mercury’s, once said, “It’s fairly obvious to me that [‘Bohemian Rhapsody’] was Freddie’s coming-out song.”

This sentiment has prompted many to wonder whether or not an “official” coming out on Freddie Mercury’s part would have changed his relationship with his audiences. As Jones believed, “Freddie was resisting the inevitable: having to end his relationship with Mary [Austin, his partner for many years] to start a new life as a homosexual. But the thought of doing so terrified him, so he kept putting it off – not least because he dreaded the effect it would have on his parents.”

She went on to speculate that “coming out could have made his life so much easier in the long run, as it had for Kenny Everett [a close friend of Freddie’s and the DJ who first played ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’], who alienated neither his fans nor his wife with his honesty.”

English record producer and manager Simon Napier-Bell deduced that Mercury coming out would have been groundbreaking. “It wouldn’t have been like George Michael, who only came out when he was forced to,” he explains. “Had Freddie come out, he would have rubbed homophobe noses in their own hypocrisy, and it would have been a smaller step than he thought — because to all his friends he was already out, and outrageous.”

“When he said he was different in his private life from the performer he was on stage, what he really meant was that he was forced to retire into his shell because of the fear his Parsee family would have had of him coming out,” Napier-Bell continued. “Had he come out from the beginning, his long, slow death would have been something that the gay community could have thanked him for. They would have used it to their advantage, turned it into something wonderfully, tragically show business, and made him the new Judy Garland. He might even have found himself enjoying it!”

All that said, it’s hard to deny that Freddie Mercury was a queer icon. His flamboyant stage persona, his leather aesthetic, his “gay clone” look (which consisted of “closely-cropped hair, bristly moustache, a muscular upper body, and tight denim jeans”), the open secret of his bisexuality (regardless of remaining officially closeted), and a mountain of songs — from “Somebody to Love” to “Under Pressure” — solidify that.

The problem, then, lies in the way history has chosen to remember him, simply as a flaming frontman or as a gay man, bisexuality erased and deeper looks into his life left in the shadows. Bohemian Rhapsody shamefully reinforces these things in its revisionism, a problem that stems from both its PG-13 rating and the fact that the surviving straight members of Queen had too much of a hand in telling a dead queer man’s tale.

Anthony McCarten, writer of Bohemian Rhapsody and other Oscar-bait biopics like The Theory of Everything and Darkest Hour, positions Mercury’s queerness and indulgences as something inherently negative. The only route to happiness is heteronormativity, or something akin to it. While it is true that Mercury only had two steady partners that he cared deeply about — Mary Austin and Jim Hutton — the implication that the nightlife was what ruined him is misguided at best, homophobic at worst.

The romance between Freddie Mercury and Mary Austin is at the core of Bohemian, something that both Rami Malek (Mercury) and Lucy Boynton (Austin) convey beautifully. They offer two shining performances in a film full of shallow characterization, even for the other members of the band (mostly reduced to comic relief with the occasional dramatic flair).

McCarten, in partnership with director Bryan Singer (and uncredited director Dexter Fletcher, who took over after months of shooting and Singer’s firing), presents their relationship as the apex of Mercury’s happiness. Every queer person introduced prior to our meeting of Jim Hutton serves as a distraction, a fling, or an outright villain; always proving more important than his straight compatriots and leading him into drug use.

On screen, a recording of the song “Another One Bites the Dust” is accompanied with deep red lighting and the most tame imagery of a leather bar ever caught on film. It is meant to be a sign of the sinful, and deadly, depths Mercury was crawling into to get off; a very uncomfortable visual wink and nod that equates the song to AIDS.

Mercury acknowledges he is bisexual to Mary Austin and is promptly corrected: “Freddie, you’re gay.” This marks a moment in the film where a rift builds between Mercury and Austin that is only fixed years later, a stark contrast to the close friendship they maintained over the years. Not only was she involved with taking care of Freddie late in life, but she toured with Queen after their break-up as secretary to the band’s publishing business, and he even left Mary the better part of his wealth.

Worse than a simple misrepresentation of their relationship, it is an outright denial of who Mercury was. The film addressing bi erasure with a scene like the one described could have been a powerful statement. Instead, it confirms this dismissal of his sexuality by never allowing Mercury to date or sleep with another woman, even though it is well-documented that he had.

Take, for instance, actress Barbara Valentin, who worked with Rainer Werner Fassbinder for much of his career and took Freddie Mercury on as a lover for quite some time. She would become “Freddie’s live-in lover and almost constant companion — bizarrely sharing him with both Winnie Kirchberger and Jim Hutton, who were also his lovers,” Jones explains. Polyamory and bisexuality? A PG-13 movie could never. Even after she realized Mercury was HIV+, she continued dating him. And after a rough break-up, a friendship blossomed between the two later in life.

In the film, Jim Hutton is reduced to a sexless being, initially rejecting Mercury, chastising him for being sexual, and offering friendship above all else. He tosses in a “Call me when you find yourself” before walking out. His only other presence in the film is as accompaniment to Live Aid, staring in wonder at the singer performing, before the credits note that he was with Mercury until his death. He lacks any personality in his minor screen time, a stark contrast to the deep characterization that Mary Austin got. This simplification of their romance couldn’t be further from the truth.

Mercury first hit on Hutton in 1985, while dating both Valentin and Kirchberger, at the Copacabana with his usual pick-up line: “How big’s your dick?” They spent the night together. Hutton didn’t hear from Mercury for months (due to his tax exile in Munich), and then got a call out of the blue inviting him to a dinner party. The start of their relationship was long-distance: Freddie flying to London one week, Jim flying to Munich the next. When his exile in Munich had come to an end, it was Jim — not Barbara — that Freddie chose as his live-in partner. Jim, who discovered he was HIV+ himself, did not leave Freddie’s side until his death (though the two lived with numerous others, some former lovers, in their home together).

In Bohemian Rhapsody, DJ Kenny Everett is reduced to being a gay friend that Mary suspects Freddie is cheating on her with, instead of a man that maintained a lengthy friendship with the lead singer and helped his career by debuting and playing “Bohemian Rhapsody” 14 times over one weekend. Their friendship was actually only fractured by the expose that one of Mercury’s supposed close friends gave the world. That man was Paul Prenter.

On screen, Mercury’s personal manager and friend Paul Prenter spends the entirety of his time with Freddie leading him down the wrong roads, making bad decisions, and encouraging his drug use and sexual proclivities, only to sell him out after their split. The film posits that by bringing him all the sex, drugs, and alcohol that Mercury wanted, he was corrupting the man until he was cut off. The truth is that this is what Mercury wanted, until he didn’t, and he wasn’t manipulated into this. Often times, Paul and Barbara even competed for his attention by seeing who could provide the grander spectacle.

Prenter’s genuine villainy lies in how he sold out Mercury, revealing every little detail he could about the man to the News of the World for £32,000. Bohemian Rhapsody frames this betrayal as being prompted by the way Prenter was cut off by Mercury when he decided to clean up before Live Aid. The truth is that it happened later down the road, and many have speculated it was actually prompted by Prenter’s resentment of Mercury and Hutton’s relationship.

There is no denying this was a man who took advantage of Mercury, but the way the film places him as a force of pure evil — cutting him off from his bandmates, encouraging hedonism, and pushing him toward isolation — is bullshit and an easy way to imply that queerness was Mercury’s downfall.

To think about how much is missing from Bohemian Rhapsody hurts, not simply because it doesn’t paint a full picture of the man we know as Freddie Mercury, but because it paints something that doesn’t feel honest. It feels like a film made by the remaining members of Queen, for an audience that isn’t actually queer; a film made for some, not all. Freddie can be treated as someone who needs forgiveness, as someone less than good, because he left the band for a short time, because he was too busy being seduced by a queer lifestyle of sex, drugs, and alcohol, because he wasn’t like the rest of them.

But not being like the rest of them is exactly why Freddie Mercury was so iconic. Freddie Mercury was as messy as he was amazing. He made music that made him feel good and made the audience feel good. He lived his life rather shamelessly, for better or worse, and there’s something beautiful and queer about the way he existed. He was a “fuck you” to what the lead of a band was supposed to look like, was supposed to act like. He was, in every way, queer. And he is, undoubtedly, an icon who deserves to be remembered as he was.

Illustration by Bronwyn Lundberg

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox