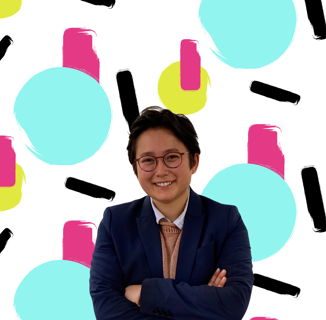

As a lifelong ballet dancer, Ashton Edwards has always strived to give audiences the best version of themselves. In so doing, they’ve challenged gender roles at the professional level as a proud, nonbinary performer. And if the gender-blind standards that have followed from their efforts are anything to go by, they’re already succeeding at shifting the landscape.

Edwards grew up in Flint, Michigan, where they first enrolled in Flint School of Performing Arts at the age of four, shortly after watching a production of The Nutcracker. Their dancing showed promise right away, with teachers praising their serious dedication to the craft. At the same time, barriers intrinsic to the art of ballet were also becoming apparent.

For one, ballet is a highly gendered art form, especially in the case of classical productions based on fairy tales. Male and female dancers are often set off one another in implied romances on stage. There are even certain maneuvers that are restricted by gender—for instance, cis men traditionally do not dance on pointe (on their tiptoes with reinforced shoes) and cis women traditionally do not perform lifts.

For a nonbinary dancer like Edwards, this revelation was devastating. “I would search and search for footage of ‘Swan Lake’ with Baryshnikov as the swan. And it didn’t exist,” they told The New York Times.

Gender is far from the only concern in ballet: Ashton is also a person of color, often going up against a legion of white dancers for scarce roles. “I’ve had to be 12 times better than everyone else my whole life,” Ashton told Dance Spirit last June. “We have no choice but to be the best if we want to be treated equally.”

Edwards persisted in their dance education in spite of these challenges. They spent twelve years at the Flint School of Performing Arts, and by the time they turned eleven, they started pursuing their craft even more seriously, seeking training out-of-state during the off months of school. At sixteen, they auditioned for a summer intensive at the Pacific Northwest Ballet (PNB) company, where they were noticed by director Peter Boal. “There are dancers that you just look at them, and they have their own special spotlight,” Boal told DS.

By 2020, Edwards had become an advanced student at PNB, the same year that COVID forced the theater to temporarily close its doors. Ever the dedicated learner, Edwards continued to train. But the shutdown also afforded them a moment of self-reflection. They made the decision to disregard gender restrictions in ballet—come what may—and trained themself to dance en pointe.

After six months, they approached Boal to request formal on pointe training at the school. Boal quickly agreed, astounded at what they had accomplished in such a short amount of time compared to the many cis female students who are trained en pointe for years.

“I definitely want to be an activist for the next generation, and I also want to be a light for them, to show them that it gets easier on the other side.”

Since then, Edwards has become an official apprentice with the company, performing in The Nutcracker and Cinderella en pointe. Consequently, genderblind dance training has become standard practice at PNB: Edwards’s simple request was the spark for a new nonbinary normal at a company now celebrating its 50th anniversary. “Ashton led us there,” Boal told NPR. “Ballet can be a little bit slow [in terms of progress]. We said, ‘Why not? Lead us and we will work with you.'”

Edwards is not the first nonbinary ballet dancer to ever perform traditionally feminine roles. Often, cis men will play the roles of women for comedic effect. A famous example of genderbending ballet is the Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, a drag troupe that was founded in the wake of the Stonewall riots. But Edwards is not performing in drag—they are performing proudly as themselves.

Doing so has not always gone well for other dancers. A veteran performer at PNB, Joshua Grant, recalled to DS being told in 2006 that performing on pointe would be “career suicide.” And as late as 2018, Chase Johnsey performed a female role in a production of Sleeping Beauty and summarily found his career in ballet stunted. “Every ballet company that I tried to go to? Nothing happened,” he told The New York Times.

Edwards’s success is owing to their own merit, thanks to rigorous training and dedication throughout their life. They are also standing on the shoulders of those who came before, and they are doing so en pointe.

Ashton Edwards has been an apprentice at PNB since 2021, and they have since been awarded the Princess Grace Award in recognition for their emergent career. Outside of PNB, they perform with Ballet22, a studio opened by a former Trockadero member dedicated to gender inclusivity.

For the future, Edwards envisions their career as a way of opening doors for others. They told The New York Times, “I definitely want to be an activist for the next generation, and I also want to be a light for them, to show them that it gets easier on the other side.”

They are also seeking to change the nature of ballet itself. “I want to be part of changing, evolving those traditions to modern day life,” Edwards told DS. “We can preserve those ballets, those classic works, but also make them reflect our modern world.”♦

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in 20 Under 20

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox