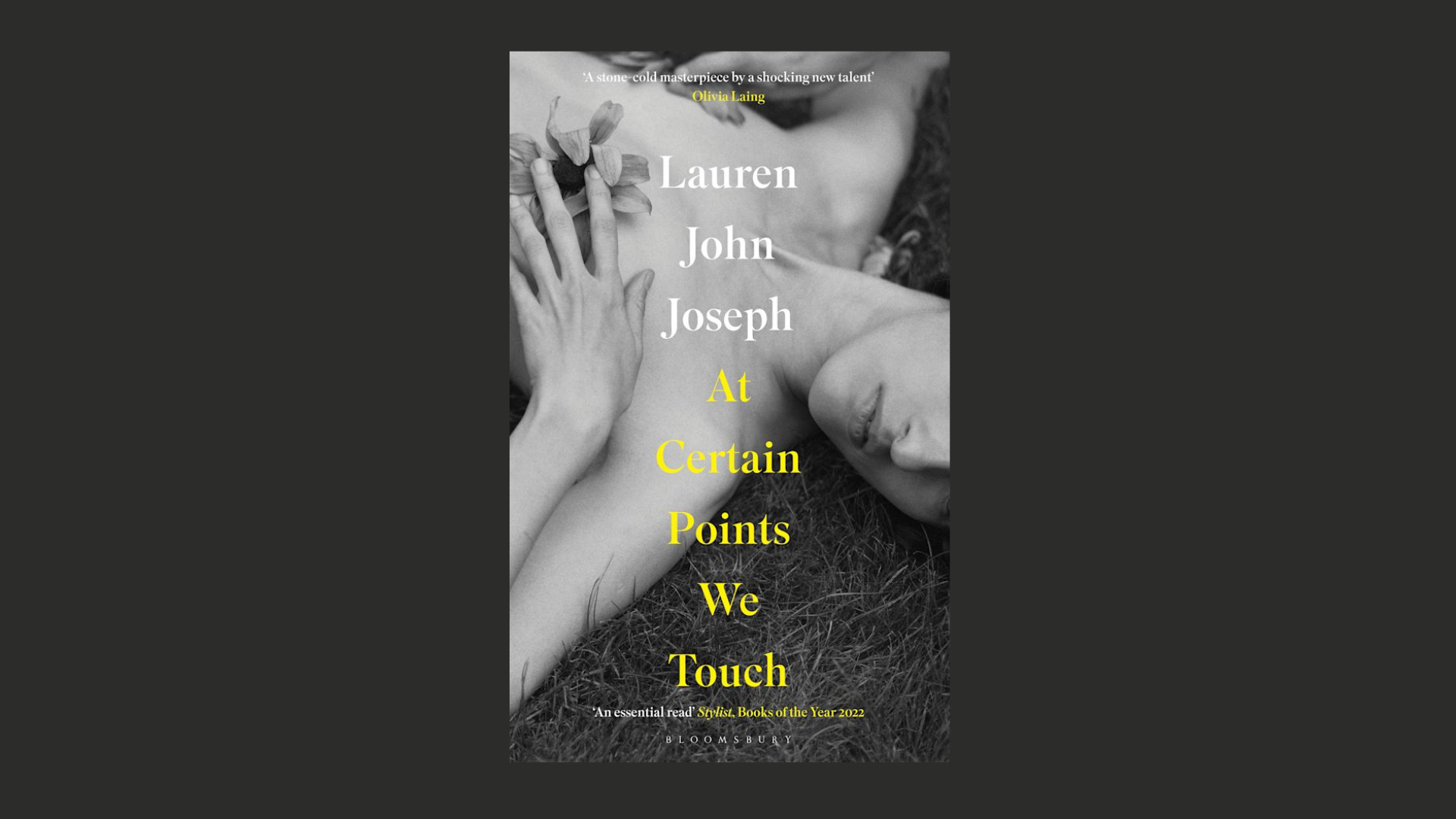

Lauren John Joseph’s At Certain Points We Touch has all the hallmarks of a novel I almost certainly won’t like: It’s about an aimless main character who hangs out with unreliable, irresponsible friends, does drugs with them and is involved with a man who, most of the time, seems repellent. But I loved At Certain Points We Touch, as do the acclaimed, queer writers Jeremy Atherton Lin and Olivia Laing. Joseph was named by The Observer as one of the best debut novelists of 2022. At Certain Points’ main character and narrator, named after Joseph (but using their former name: they have a long résumé as a playwright, filmmaker and performance artist) follows the author’s own footsteps from London to San Francisco to New York and Mexico City. It’s a reminiscence of their relationship with the repellent man, Thomas James, who only occasionally betrays his feelings for them and who, years later, dies at a sceney London party.

The novel was published in the UK this past spring and in the US in December. Joseph spoke with INTO by Skype from their home in London.

INTO: I was struck by the sex in the book. In novels by straight, cis women, the sex, when it’s with a not-great guy like Thomas James, makes me wonder “Why are these people hooking up?” But in your book, the sex clarifies the relationship. What inspired you in writing the sex scenes?

Lauren John Joseph: With straight, cis women and bad men, the damaging, old-hat default is to fetishize the bad guy because he’s hot. Without sex, you would think about my two characters: “Why on earth are you together?” The unspoken connection that they feel calls for breathing space and a tonal shift. Some writers who inspired me are Garth Greenwell in his novels What Belongs to You and Cleanness, and Andrea Lawlor, who wrote Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl.

The protagonist gets an STI from Thomas James, and, like one of the main trans characters in Torrey Peters’s Detransition Baby, compares the STI to pregnancy. Were you paying homage to Peters or did the metaphor come to you independently?

I read Detransition Baby after my book was finished. A sense of trying to escape shame is in my book and Detransition Baby. Both books also share an ambivalence to gender, that it’s not a “yes” or “no.”

The protagonist talks about the process of leaving masculinity behind. When I read articles about you from the mid-teens, the pronouns were all over the place. Did you find that frustrating or did that reflect where you were at then?

It was frustrating. Even today people write about any nonbinary person ”the artist who identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns,” and after that preamble, someone then immediately called me “he.” I never use “he” but I’m flexible with “they” and “she.” I’ve done performance projects where I’ve used other names and other gender identities and people try to make that persona me. It happens with this book. The protagonist has my old name and childhood, but it’s fiction.

Related: Can Gay Bars Survive Without Sex in the Air? An Interview with Jeremy Atherton Lin.

The protagonist lives, as you have, in far-flung cities during the course of the book. Can you talk about living in countries where you didn’t have the ability to work and how that affected your development as an artist?

There’s a quote from The Cockettes, “All of our friends were busy. None of them had a job, but they were all so busy.” Being unemployed is full-time work, because you’ve got to scheme and be on guest lists. Artistically, it was difficult. If you don’t have financial resources, there’s only so far you can go.

In the parts of the book set in Mexico City, the protagonist goes to Mass. What’s your relationship with the Catholic church?

View this post on Instagram

This book was an investigation of Catholicism. After I wrote it, I joined a Jesuit, LGBTQIA+-friendly congregation. When queer refugees come to the UK, they’re asked, “How can you be queer and a Catholic?” Priests from my congregation go with them and they get people visas. I feel toward the church as I feel toward my national government, a participant, but not uncritical. The world has a billion Catholics. [Nearly] everywhere you go, you see Catholic churches and Catholic festivals. You can, if you’re a weary world-wanderer like me, feel at home in many places.

She doesn’t appear often in the book, but I like your portrayal of the protagonist’s mother. When the protagonist first comes out as gay as a kid, she says, “After all the trouble I’ve had with fellas?” Has your mother read the book?

No. When The Observer, a national newspaper had a feature on my book, I told her, “Hey, this is in the newspaper today. Have you seen it?” And she said, no. And when I said, “Well you live next door to a newsagent: why don’t you get a copy,” she asked, “Do you think I can find it online?” She likes reading fantasy fiction: wizard queens and dragon overlords. She did read 50 Shades of Grey. She said, “Actually, it’s a very conventional love story. It’s just that they have some unconventional interests.”

You can, if you’re a weary world-wanderer like me, feel at home in many places.

At one point the narrator is thinking back on all the times they dismissed something racist or anti-immigrant Thomas James had said because they thought he was trying to provoke them. And then they realize somebody who says racist things is a racist. In the white, queer cis, male community, racism is not only common, it’s sometimes seen as attractive. Can you talk about the appeal of fascism in the white queer community?

Thomas James’s constant racism is disguised as banter. Much of white, gay, male, queer culture is based on this pose of flippant, slightly catty racism. When you look at Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance, or you look at Virginia Woolf, another canonical, queer, white writer, their way of viewing the world has a casual, tee-hee-hee snobbery, antisemitism and racism that informs the pose of the modern, urban, white queer. When people adopt this pose, other white people let it slide because they don’t want to seem uncool. I wanted Thomas James to provoke some self-reflection in readers: “He says these terrible things. But my friend Tony does too.”

I wasn’t surprised to find out the friend you based Thomas James on did die and his death was in the papers, because you capture the dissonance of that experience. Can you talk about how news coverage distorted his death?

The character represented in the newspapers was a trope wheeled out as part of an ongoing, homophobic culture war, not the person I knew. When someone is gone, all that remains is what people say about them, whether it’s true or not.

View this post on Instagram

The protagonist goes out a lot, even when they’re avoiding bars and events where they might run into Thomas James. During the early part of the pandemic, no one could go anywhere. Did that pause period affect how you felt about going out when things started to reopen?

Yes, though it’s difficult to extrapolate the impact of the pandemic from other shifts. When the pandemic started I sold this book and moved in with my now husband. What I did learn to love during the pandemic was nature. Where I live in London isn’t beautiful, but it is surrounded by countryside. Once a week, we find a national trust property or a bird sanctuary. I’d never been interested in the natural world before. I’m afflicted with rather horrendous ADHD, and it’s the one time my mind is quiet. I’ve tried the drugs, I’ve tried yoga, and I’ve tried white noise and nothing else seems to do it.

You’ve been prolific in both performance and writing. The stereotype of somebody with ADHD is that they wouldn’t be. What are some other ways you work with your ADHD?

ADHD is, like a lot of neurodivergence, misunderstood. It can lead to intense hyperfocus. I can write 5000 words a day, as I did for At Certain Points We Touch. The problem is if I’m bored. I’ve been fired from jobs, because I’ve had to climb out the window halfway through the day. ADHD also influences my writing in its switches from verbose to vulgar and in what forms my art takes. I’ve made short films and performance pieces and written prose and now novels. I wasn’t sure this book was a success until I recorded the audio. Reading the book out loud made it a performance piece. But it was a trip to work with the world’s straightest sound engineer. He would say, “Uh, Lauren, sorry, can we go back to ‘throbbing, hard cock’ and pick it up there?”

Congratulations on your wedding. I saw the announcement on Twitter. Marriage seems like the last thing on the mind of your protagonist. Can you say a little about how you came to settle down with your partner?

We met at a Perfume Genius concert. At the time, he was a hairdresser, and he gave me his business card. At first I thought, “What are you, cruising for clients?” I’ve learned so much about myself and the world through loving him. And even though he’s no longer a hairdresser, he still does my hair for events!♦

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox