When I was in 4th grade, I got a dolphin plush. I decided to give my new best friend a gender-neutral name. The reason for this was that the plush didn’t display any external sexual characteristics, so it would be rude of me to engender the creature and get it wrong.

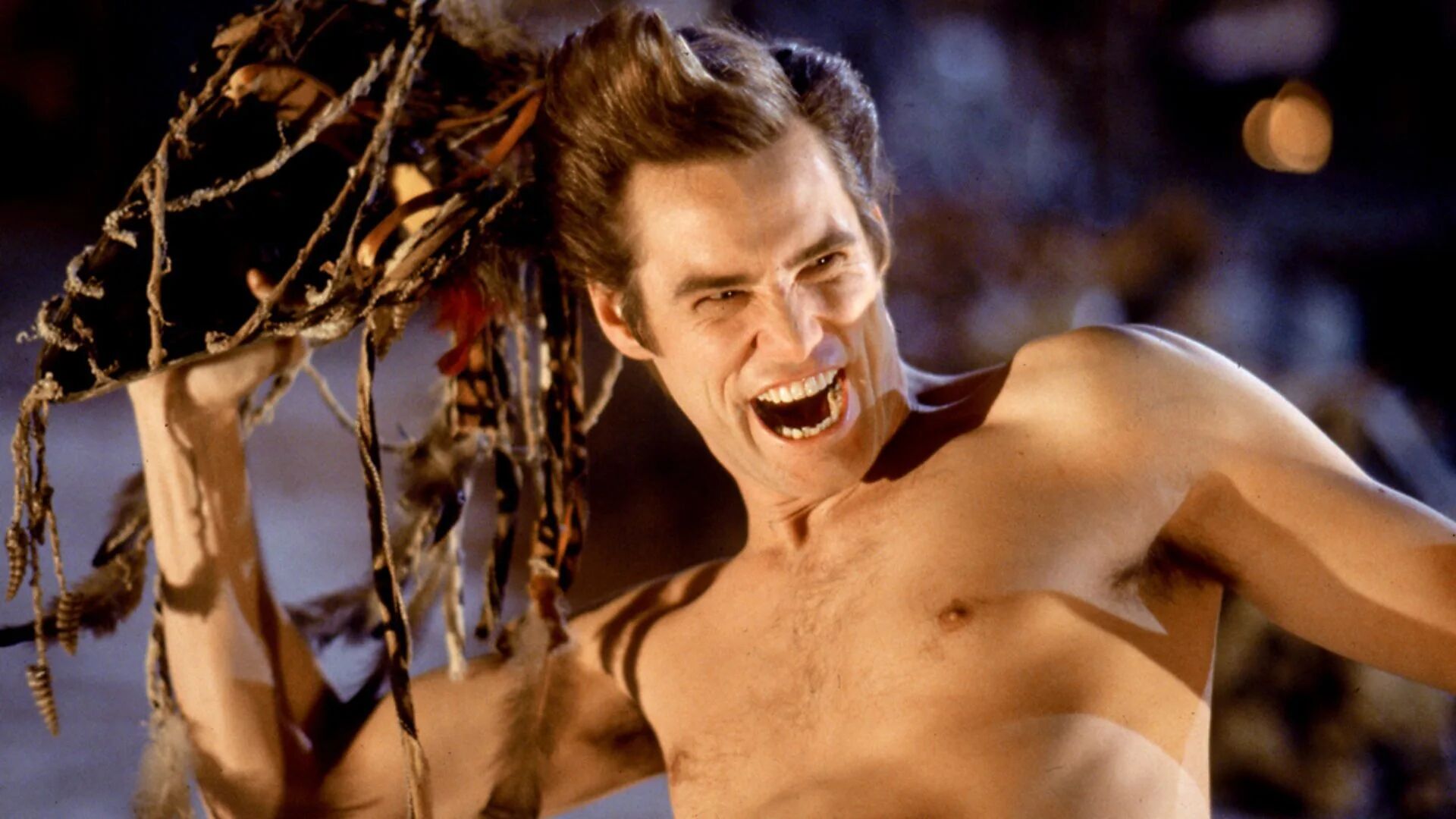

At the time, dolphins were my favorite animal because they represented everything I wanted to be: sleek, graceful, and able to spend most of their time in the water. It was a quest for dolphin media that led me to Ace Ventura: Pet Detective late one night nearly a year or so later. It had everything that a rising middle schooler could want: a blend of comedy and action, Jim Carrey making funny faces, and, for me specifically, a plot based around recovering a kidnapped mascot for the Miami Dolphins. Today, the film is most remembered for its particularly egregious transphobia. But as a kid, it quickly became one of my favorites.

Make no mistake, Ace Ventura is some of the very worst queer representation, but little has been written on why exactly it’s so bad. The answer lies in a mistranslation and simplification of complex gender politics in order to appeal to teenagers and children. Ace Ventura is a parody of police procedurals (particularly Miami Vice) and to a lesser extent film noir, but fails to understand (or even seem to acknowledge) femininity’s existence in either genre. If detective fiction found its edge through inversion, and the claim that evil can hide itself behind the facade of femininity, then Ace Ventura re-adjusts this focus to contend that homosexuality is, in fact, the true evil which hides and must be uncovered.

Related:

What Doris Wishman Got Right (and Wrong) in the Transploitation Classic “Let Me Die a Woman”

Wishman’s prolific career spanned decades, as she turned out low-budget, boundary-pushing exploitation films that addressed subject matter Hollywood would rarely touch.

The film is chock full of masculine anxieties, finding its main tension in Ace having to legitimize his unconventional (dare I say metrosexual?) masculinity in the eyes of football players and police officers who don’t take his line of work seriously. Ace makes up for physical strength by being a smooth-talker and a self-confessed “animal in bed.” Yet the threat of homosexuality—unacceptably horrifying in 1994—looms large. What’s strange is that—save for a busty housewife who rewards Ace for finding her stolen puppy with sex—hardly any femininity is actually present in the film. Even police Lieutenant Lois Einhorn, whom my memory recalled as a femme fatale, falls more in line with the archetype of a heartless career girl who denies her femininity only until the point where she needs to throw someone off her trail. If Ace‘s conflict is that he’s a straight man who’s constantly treated as queer, Lois is the perfect antagonistic counterpoint. She’s a woman whose masculine characteristics further threaten his legitimacy.

It was a quest for dolphin media that led me to Ace Ventura: Pet Detective

However, the film resolves this tension by revealing that Lois is trans and thus (in the film’s eyes) simply another man for Ace to outwit. However, there are two readings a viewer might have of Lois. There’s one where she is trans (or intersex) and one where she uses simply uses the hallmarks of transness as a means to get away with crime. While the non-trans reading has an easy parallel in the popular TERF claim that men will often “claim” transness to do harm, the direct trans reading of Lois is far more tragic.

Lois’s motivation for revenge stems from being a former Dolphins player and being blamed for costing them the Super Bowl. While she blames a misstep by her teammate, it doesn’t matter. Once “exposed,” she is suddenly an object of ridicule and shame, forced to hide from the harassment of former fans and eventually placed in an insane asylum for threatening the man she blames for her downfall. Reading Lois as a trans woman makes it easy to understand her rage, because imagine the betrayal that comes from having the full social weight of masculinity leveled against you for failing one of the highest masculine feats: namely, winning the Super Bowl.

Lois’s transition comes not from a love of femininity, but an alienation from masculinity. If Ace spends the film having to prove his masculinity outside of traditional means, Lois commits the sin of abandoning her masculinity entirely. In Ace’s own words, she’s a loser who cannot take responsibility for her failures or “the truth of her body.” In a damning portrait of straight masculinity, Ace gains his legitimacy not through his own merits, but by proving that Lois is the true failure of masculinity instead.

Puberty hit me early, fast, and hard. While I was never a small kid, puberty ensured that I entered 7th grade at twice the size of my classmates. At the time, my class was going through a football craze, and our PE teacher started a lag league. Someone put my name in without my knowledge, and our teacher was insistent that I play. After all, I was the closest thing the school had to a proper linebacker, but yet within me was a searing hatred for football. All of my girl friends had steadily left, and the boys had suddenly become infatuated with this dumb, brutish game. I was stranded and, not unlike Lois, trying to find myself without the language to do so, abandoned by a social masculinity that wanted me to do something I’d never be capable of.

I decided to protest the league. I made a sign and stepped onto the field as they began a game. Standing there alone, I could feel tears building up. Perhaps I was imagining myself as Lois in her final scene, surrounded by men on all sides, lashing out like a cornered animal. A strange man strips me down to reveal the horrors of my queer body to which this audience pukes in disgust. Why couldn’t I live up to their standards of masculinity? At a certain point, a friend got me off the field. One of the players wanted me suspended. My mom was proud that I stood up for my beliefs.

As for me, I wanted to be alone. I went to my room and slammed the door. I grabbed my dolphin and cried.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox