“The ’50s weren’t really like that,” my mother used to say when I was a kid watching Happy Days. She insisted the show had denuded the 1950s of everything that defined it. In a South Boston diner when she and her friend played Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill” on the jukebox, the older adults looked at them with contempt, as if they had come in arm-in-arm with Domino himself.

I was a queer teen in London in summer 1983, the time in which Call Me by Your Name takes place. Like the protagonist, Elio (played by Timothée Chalamet) I lived in a grand house–the last I heard Sting had bought the place next door. The people I lived with, like the family in the film, came from money and also like the characters, I went on frequent swims nearby–my spot was the women’s pond at Hampstead Heath, the first place I had ever gone swimming where women went topless.

But nothing about Call Me by Your Name (except for some brief moments of internalized homophobia) resonated with what I remembered, and not because the love story is about two men. What the film leaves out is the queer art, queer artists, and queer signifiers that were a huge part of the culture for young people, especially queer, young people, in 1983.

Armie Hammer’s character, Oliver, does name check The Psychedelic Furs’ Richard Butler (and in a much-memed clip dances to “Love My Way”), but nothing about Oliver’s dull, conventionally masculine, somewhat preppy non-style is like Butler’s, a straight guy who wore eyeliner and elaborate “big hair.” Butler wasn’t the only one: straight women like Grace Jones and The Eurythmics’ Annie Lennox performed in drag and had super short “androgynous” haircuts. In 1983, queer influence, though barely perceptible in most TV shows, ruled MTV

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

But even as Culture Club had number one hit singles, their singer, Boy George, wearing makeup that made his face look like a Patrick Nagel illustration, wasn’t out to the general public. He and the drummer later revealed they had been a couple during the band’s heydayand some of their most popular songs had been about their relationship.

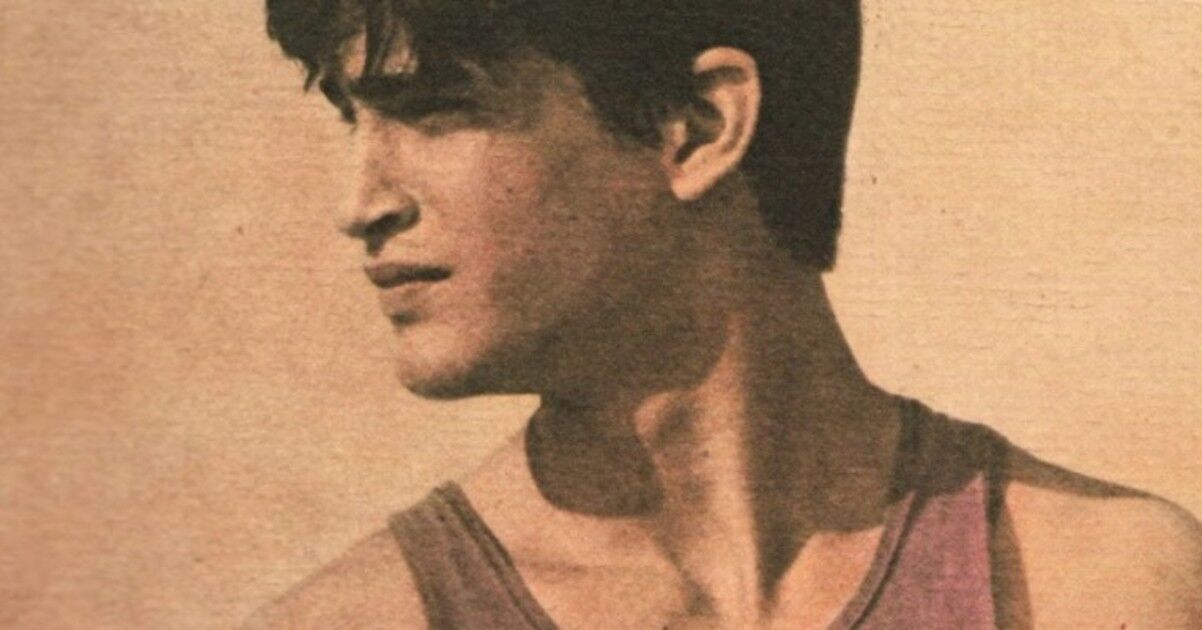

In the film Pride, based on a true story, a London-based queer group in 1984 organizes a fundraiser for striking coal miners called “Pits and Perverts” (which should have been the name of the film) and goes to the offices of a big record label to ask if any of the talent can perform. The label tells the group they don’t have any gay artists, as giant photos of Elton John and Soft Cell’s Marc Almond loom over the lobby. Just a few years before, Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love” had been a huge hit, and Almond appeared in the video (which was in heavy rotation) with kohl-rimmed eyes and a short, white tunic like a kicky miniskirt; his pale, skinny body and floppy, top-heavy dark hair have a passing resemblance to Elio’s. But Almond wasn’t out to his fans as queer, even as many LGBTQ people first experienced queerdar when they saw him.

The novel, from which the film is based, written by a straight man, André Aciman, also pays no attention to the burgeoning queer culture of the time. Even though Aciman has Elio and Oliver visit bookstores, A Boy’s Own Story, the groundbreaking, semi-autobiographical gay novel by Edmund White (and an international bestseller in 1983) doesn’t make an appearance.

Oliver and Elio first connect in the film dancing, separately, to the same Psychedelic Furs’ song and later when they are in Rome, Oliver dances to the song in the street with a young woman in post-punk clothes as Elio watches. But in neither the film nor the book do the two men go to a Roman gay bar where they could dance together, though they might have rolled their eyes at the music there. If Elio and Oliver, in search of music more to their liking, had gone to a post-punk show in Rome, they probably would have seen other queer couples, too. LGBTQ people were always in the crowd when I went to those shows in London.

Elio studies classical music and Oliver studies Ancient Greek philosophy and Hellenistic art, but in both the book and the film neither character seems to consciously notice how many queer men make up the canon of each discipline. What the book and the film both miss is the instinct of queer people to seek out, in art and in person, other queer people.

But the book and movie do include a scene in which Elio makes fun of an older gay couple in matching outfits to prove to himself he’s not like them (later in the ’80s, a girlfriend and I, in what was not our finest moment, made fun of a woman couple in matching outfits, too). As in many films and on TV queer people never have queer friends, just unrealistically supportive, straight (or in the case of Mr. Perlman, Elio’s father, as the book makes clear, mostly straight) friends and family.

Straight filmmakers naturally cast a rosy light on straight characters. But gay men made Call Me By Your Name (though the actors who play the main couple are, pointedly, straight). Director Luca Gudagnino was a child in 1983, but screenwriter James Ivory (one of the oldest Oscar nominees this year, less than a week and a half younger than Agnes Varda, the co-director of Best Documentary nominee Faces Places) was a 50-something director, in the middle of a 40-year professional and romantic partnership with Ismail Merchant (though the two were always described as business partners) with his most acclaimed work yet to come. He was old enough to have seen queer culture go through several iterations before 1983, and saw the backlash afterward, when Section 28 was passed in Britain and anti-sodomy laws (used exclusively to arrest and prosecute queer men) upheld by the US Supreme Court.

But these and other homophobic measures were like dams trying to keep out the ocean, as queer culture continued to flourish and the outrage over the AIDS crisis led to a resurgence of queer activism that toppled the backlash, well worth remembering as we see that tide perhaps recede.

Apparently, some of that’s being saved for the sequel.

Helen Terry and Boy George photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images; London Pride ’83 photo by Photofusion/UIG via Getty Images