Conversion therapy and the unfortunate consequences it has on the physical and mental health of LGBTQ+ people has been thrust into the spotlight more than ever, as of late. The practice, still allowed in numerous states, refers to any attempt to change a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.

These attempts have been displayed prominently in the media, from the satirical But I’m a Cheerleader to the more dramatic approaches in Boy Erased to horror films like They/Them. And while these films depict the horrors of conversion therapy, they’re told through the eyes of someone else. With the documentary Conversion, the stories come straight from the mouths of survivors.

Giving Survivors a Platform

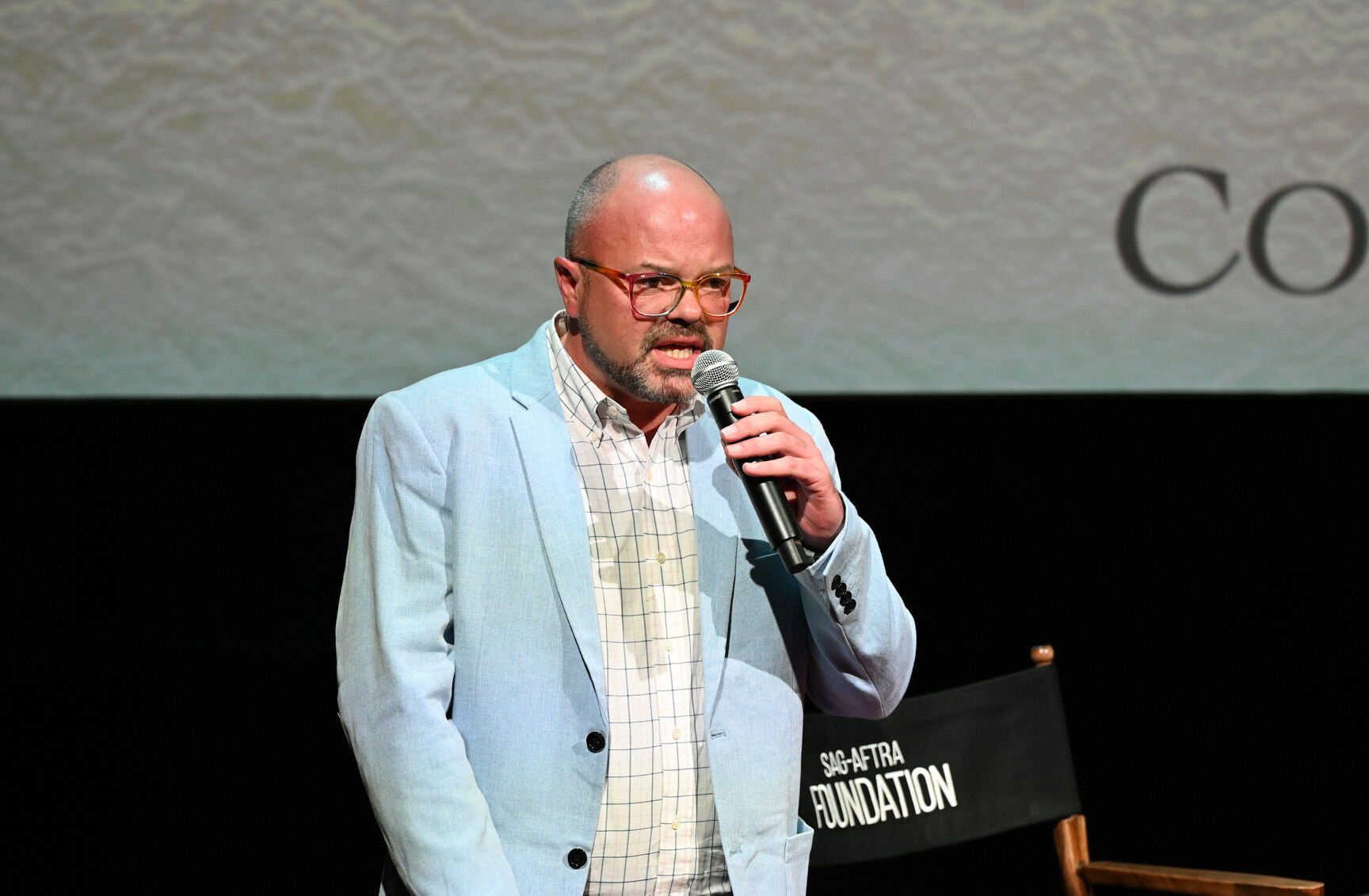

Zach Meiners (he/him), the filmmaker behind Conversion, is using his film to not only tell his story of overcoming conversion therapy, but those of many others subjected to this practice. Although the film is out now, it took 4 years to bring it to fruition. And yet, it all stemmed from a life changing event in 2018.

“So I initially found out that my former conversion therapist was still practicing,” said Meiners. “A family friend of ours was going and his parents sent him to the same person that I had gone to see, and I was shocked.”

Having found out that someone he knew was now being subjected to the same harmful practice, Meiners made the conscious decision to create the film Conversion. But it wasn’t a documentary, at first. It was a public service announcement (PSA).

“I just wanted to make a five minute PSA. I thought I wanted to tell my experience. One of the corporate clients I was meeting with said, ‘You have to expand this bigger because people are going to say, “Of course that happens in Kentucky”’, but it’s also happening in New York and California. One of the largest conversion therapy organizations in the world is like 30 miles outside of L.A. and a lot of people don’t realize that.”

Meiners came out as queer in 2016 and in 2018 he went on a date where he experienced RuPaul’s Drag Race for the first time. Meiners was introduced to drag performer Dusty Ray Bottoms a.k.a Dustin Rayburn (they/them). Rayburn, was an established performer in New York City when they became a contestant on season 10 of the acclaimed drag competition reality show.

Conversion Therapy and Religion

As Dusty Ray Bottoms, they were known for the unique dotted makeup designs and dark, glamorous aesthetic. But they also became known for their story dealing with conversion therapy.

“When I first shared my story with conversion therapy, I had never talked with someone who had also gone through conversion therapy,” Rayburn stated. “So it wasn’t until that played on national television that people were messaging me, ‘yo, me too’. That’s when I had my first “me too” moment with that. And that was really eye opening for me. That was four years ago and we’ve been working on this film for four years.”

“I was so broken and desperate that I would have tried anything just to be straight, to get a little acceptance from my family.”

Surprisingly enough, Rayburn and Meiners grew up in the same hometown, but they wouldn’t meet until six months after Meiners saw them on TV for an interview for Meiners’ PSA project. Meiners initial interview with Rayburn was supposed to be for 20 minutes, but it lasted for 2 hours. While a PSA would’ve been fine, the project evolved to incorporate Rayburn’s voice and those who were also survivors of conversion therapy, creating the film we know today.

Conversion therapy comes in many forms. One of those ways is through the use of religion. For Rayburn, an exorcism was performed on them at 20 years old to attempt to convert them from being queer.

“While I was going through the exorcism, I was being asked a lot of personal questions, and I really wanted it to work,” stated Rayburn. “I was so broken and desperate that I would have tried anything just to be straight, to get a little acceptance from my family.”

While the exorcism was taking place, Rayburn was being asked to “speak in tongues”, an element of their religion that they grew up viewing as sacred.

“I grew up [thinking] that [speaking in] tongues was the Holy Spirit filling you, and you were just overtaken at the helmet. Now I’m having these religious leaders forcing me to speak in tongues. In my head, I was just like, ‘Okay, let’s just go along with it. Do everything they say, because the more that you hesitate, they take it as a sign that the demons are holding on.’ I just wanted it to end.”

Prior to their exorcism, Rayburn had grown up as a queer kid in rural Kentucky, who, when time for college, left their hometown behind. But even when they left for university, Rayburn still struggled with anxiety and health complications. While their exorcism was an extremely traumatic experience for them, they realized that this wasn’t the first time experiencing conversion therapy.

“I realized that my exorcism wasn’t my only experience with conversion therapy, that my whole life, up until that point, was 20 years of conversion therapy because it comes in so many forms,” said Rayburn. “And the microaggressions that I experienced in my childhood that literally made me so sick every night before I would wake up, throwing up, and I had all these stomach problems because I was just such a nervous wreck. We couldn’t figure out why that was. And that’s because I was going through conversion therapy my whole life.”

Conversion Therapy in Adulthood

Rayburn left those who performed the exorcism behind them, but the consequences of it affected their mental health. Thankfully, they continue to live a healthy and fulfilling life, but for many survivors of conversion therapy, their mental health may continue to decline and see suicide as the only way out. Organizations, like the Pride and Joy Foundation, are working to provide resources and guidance to the LGBTQ+ community to ensure that we are mentally healthy and safely housed.

“So we have two arms. One is that we reach out to parents who feel that they want to be there for their kid and they don’t know the best way,” said Elena Joy Thurston, founder of the Pride and Joy Foundation. “The other part is that we increase the visibility of LGBTQ+ individuals. The more that these parents can see healthy, functional, happy, queer adults and [how] that can be a future for their child, too, that changes the game for everyone.”

“I found a statistic from the Williams Institute that survivors have a 92% chance of lifetime suicidal ideation,” said Thurston. “And that statistic first took me out, and then it empowered me because now I know what I’m dealing with, and I will be as proactive as I need to be to stay, because that is my whole goal, to stay.”

As a parent of four, Thurston understands and empathizes with other parents wanting to ensure that their children have the best. But she also understands the firsthand ramifications of conversion therapy. Thurston was a married, active member within the Mormon community, but that changed when she realized that she was a lesbian.

Like Rayburn, Thurston was desperate to ensure that she could find the acceptance and change she was looking for. So she turned to conversion therapy. For months, Thurston was engaged in conversion therapy, but her pain never left. Soon after, Thurston was navigating suicidal ideations.

Thankfully, she found solace in mindfulness and soon found acceptance within herself. Thurston has told her story countless times. Her TEDx talk titled “Conversion therapy almost took my life, mindfulness saved it” has been viewed over 40,000 times.

Still, her suicidal ideations persisted.

“I found a statistic from the Williams Institute that survivors have a 92% chance of lifetime suicidal ideation,” said Thurston. “And that statistic first took me out, and then it empowered me because now I know what I’m dealing with, and I will be as proactive as I need to be to stay, because that is my whole goal, to stay.”

In addition to the statistic that Thurston shared, the Williams Institute stated that survivors of conversion therapy are “75% greater odds of planning to attempt suicide” and “88% greater odds of attempting suicide resulting in no or minor injury”.

While many stories of enduring conversion therapy comes from LGBTQ+ youth, queer and trans adults are also susceptible to the traumatic practice. Thurston’s story made that very clear.

Conversion Therapy and the Political Landscape

The “rainbow wave” we received during this year’s midterm elections was felt all over the country. With over 420 LGBTQ+ elected officials from this year’s midterms, there are more people in office to combat conversion therapy.

While the Pride and Joy Foundation works on an interpersonal level, people like Troy Stevenson, Senior Advocacy Campaign Manager at The Trevor Project, are working on a systemic and political level to end conversion therapy.

“The midterm elections actually reshaped what the politics around conversion therapy would look like. As of this moment, there are 20 comprehensive bans, we call them comprehensive bans, in 20 states,” said Stevenson. “And there’s another six states that have executive orders or regulatory changes. Also, a lot of people believe this is just a religious thing, and a large percentage of it is, but we have identified hundreds of licensed practitioners around the country who are still doing this.”

There’s progress towards eradicating the practice on a systemic level, but conversion therapy is much more pervasive than what it seems. While the practice of conversion therapy is illegal in 20 states and Washington, D.C., unfortunately, that doesn’t cover religious providers of the practice.

“What we can do through legislatures and through the law is to stop licensed practitioners. It’s much harder to go into religious spaces. There’s ways to do it that’s being worked on,” said Stevenson. “But in many cases, the most pragmatic way to stop this is through stopping licensed practitioners, elevating the issue in legislatures, and in the minds of the public like what the film Conversion is doing to make people aware. Many people think this ended in the 1970s when homosexuality was removed from the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), that they don’t realize that’s when it actually got bigger.”

With the changes afoot, there’s proof that conversion therapy is being combatted on a political level. Yet, as Stevenson alluded, there are still misconceptions around the impacts of practice and who it impacts as well.

“Conversion and public education campaigns that are happening are touching on in the public psyche in society that has never been done before,” said Stevenson. “It’s hard to pass a law against something people don’t think exists, and now they’re understanding it does. That’s why Conversion is such an important thing.”

With the erroneous belief that conversion therapy only impacts white members of the LGBTQ+ community, consequently the needs of Black and Brown queer and trans people enduring this practice are eclipsed. Stevenson, who is Indigenous, found it shocking to uncover how Indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by conversion therapy.

“I was stunned to find out that per capita, the largest community that conversion currently was inflicted on were Indigenous Americans,” said Stevenson. “We have yet to figure out why that’s the case.”

Additionally, the consequences around mental health are also left undiscussed within discussions about conversion therapy. The echoes of the practice still resonate in the mental health of Meiners, Rayburn, Thurston, and many others impacted by the practice.

“Our last survey of the LGBTQ+ population in general, 11% of the youth population have attempted suicide in the last year. That goes up to 28% for survivors of conversion therapy and 27% for those who have been threatened by it,” said Stevenson. “But the jump from 11% to 28% is exponential. I think once parents hear that, I don’t care if they hate us and don’t think we should exist, most of them are not going to want to do that to their kids.”

But when public education combines with political action, the reach and impact of conversion therapy becomes smaller. This is due to the belief in the harm that conversion therapy does to LGBTQ+ folks, which pivots into affirming the identities of LGBTQ+ folks. Media plays an important role in fostering that change, which, in turn aids in furthering public discourse and fueling political action.

“Conversion and public education campaigns that are happening are touching on in the public psyche in society that has never been done before,” said Stevenson. “It’s hard to pass a law against something people don’t think exists, and now they’re understanding it does. That’s why Conversion is such an important thing.”

Moving Forward and Choosing Hope

Stevenson is right, it’s difficult to make anyone act on anything they don’t believe, but seeing is believing. With Meiners’ film, audiences can bear witness to the trials and tribulations of conversion therapy.

“It’s really hard to argue with people’s stories, as opposed to numbers,” Meiners. “And it, I think, disarms people in a way and helps people really listen.”

They can learn why the longstanding practice needs to be eliminated, but they can also can learn that life post conversion therapy is still a life worth living, in all of its queer glory.

“It was a really hard, scary, treacherous journey, but so much better for it now,” said Rayburn. “And I know that what you put out there, it comes back to you full circle.”

Rayburn is excelling in their artistry as a drag performer, Thurston is leading an LGBTQ+ nonprofit, and Meiners is still in creating films that he loves. All three are using their work to ensure that LGBTQ+ folks are seen, heard, affirmed, and receive the support they deserve.

“I hope that all of us find peace. I hope that all of us find a shared strength,” said Thurston. “And I could not have done the last two years without my crew. So I hope they’re not alone. That’s my biggest hope.”

Happiness is a journey that all three of these survivors of conversion therapy have decided to embark and they’re ensuring that everyone else has access to that happiness as well.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox