Attention all members of the cult of Jennifer’s Body: as of June 2021, the classic horror film was tastefully added to Hulu this month.

For everyone who watched JENNIFER’S BODY for the first time this weekend, WELCOME AND HAPPY PRIDE! https://t.co/hmTNOiKh5K

— Jordan Crucchiola (@JorCru) June 7, 2021

To hear the opening phrase “Hell is a teenage girl” once again hits with the same profundity it held back when my fifteen-year-old self first saw Jennifer’s Body. The only difference now is, I know I don’t have to date men; and so, the film transitions from the story of Jennifer’s demonic revenge against men to a tale centered around the intricacies of girlhood. Today, the same opening phrase that once damned the film with misogynistic generalizations is exactly what has allowed it to go through a renaissance. Diablo Cody’s instant connection between female adolescence and a pit of eternal suffering is no longer seen as a corny dramatization, but the key to the masterful allegory that was Jennifer’s Body.

Suddenly, every joke, every close-up, every exchange of glances, is granted the newfound appreciation of a uniquely sapphic lens. Being a teenage girl is its own special hell, rife with expectations of knowing exactly what to wear, who to talk to, and how to act. As such, a cult of female-identifying followers keeps dragging Jennifer’s Body from the obsolete to celebrate its unapologetic expression of how suburban America betrayed the teenage girl.

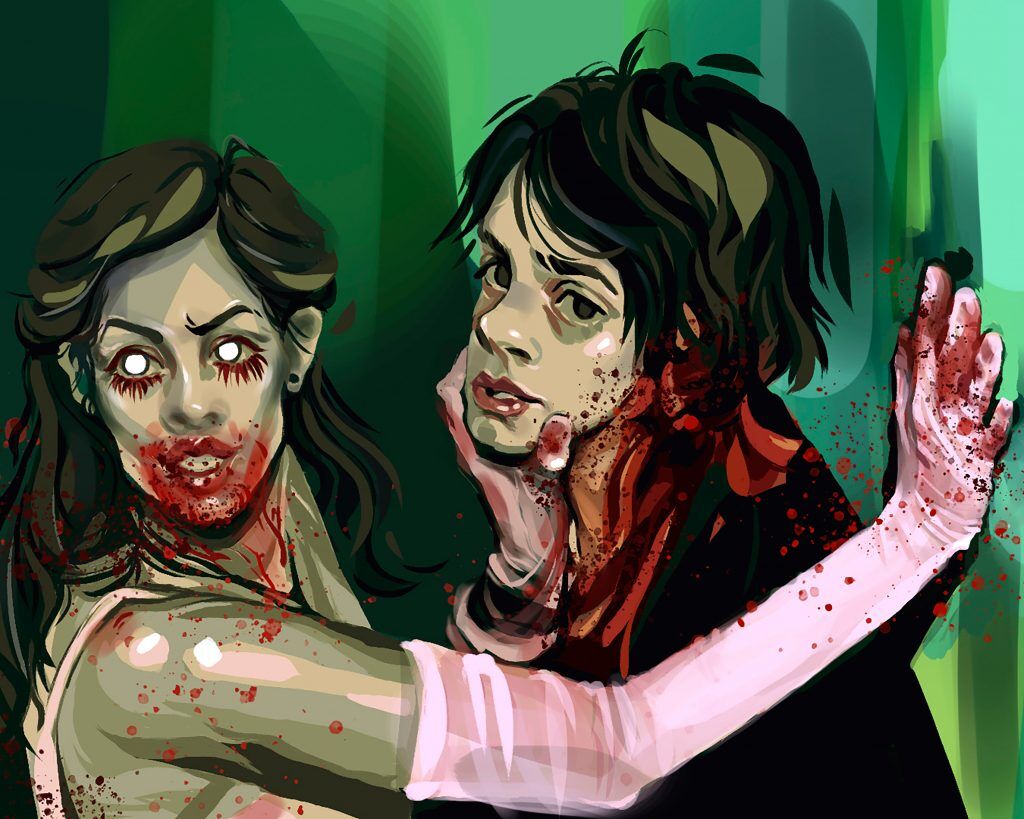

On-screen, Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfriend join Karyn Kusama and Diablo Cody off-screen to flip power dynamics inside out; together, they explore what the outward expression of a teenage girl’s interior life could look like at its most desperate. The desperation of girlhood in a patriarchal society is portrayed by Fox as Jennifer: the cheerleader next door sacrificed to Satan for fame.

A cult followers is determined to bring Jennifer’s Body back from the obsolete and celebrate its unapologetic expression of how suburban America betrayed the teenage girl.

Cody’s exploration of the hot girl requires seeing beyond the archetype Fox perfectly portrayed; It requires seeing that despite Jennifer’s perceived power of beauty and popularity, she remains powerlessly restricted to finding self-worth in the unfulfilling means of appearance. The moments in which Jennifer initially tries to empower herself—via hypersexuality—are conscious decisions to weaponize her appearance, the likes of which easily brainwash local teenage jocks. Yet, when employed in a setting of unequal power, Jennifer’s antics leave her vulnerable to the Satanic slayings of the older, out-of-town band Low Shoulder.

Cody’s exploration of the “hot girl” requires seeing beyond the archetype Fox perfectly portrayed.

That’s not to say Jennifer gets sacrificed because she’s naive, but because she is too aware for her own good. In assuming the band inquires about her virginity, Jennifer miscalculates her sexual advances as pre-emptive strikes for control when the band themselves arrived in town already prepared with their malicious intentions and a murder weapon.

When she is then sacrificed as a virgin (without actually being a virgin) the incorrectly performed ritual revives her to roam suburbia as a possessed, flesh-eating demon. In exchange for feasting on the flesh of teenage boys, Jennifer gets to stay beautiful. When she’s hungry for blood, her acne breaks out; and because she was taught to place value in her appearance above all else, feast on flesh to maintain her beauty is exactly what she does.

Fox then appears as this angsty, literal man-eater. Though Jennifer Check is still terrifyingly hot, she is not simply symbolic of sex and slasher violence, but of the disturbing, textbook unhappiness found deep within the heart of teenage girls. A dissatisfaction with oneself that runs so deep Jennifer expresses more concern over her unkempt appearance than the fact that she is forced to eat human flesh to maintain herself.

When she’s hungry for blood, her acne breaks out; and because she was taught to place value in her appearance above all else, feast on flesh to maintain her beauty is exactly what she does.

When best friend Needy, played by Seyfried, discovers Jennifer’s nightmarish possession, she shrieks shrilly, “You’re killing people!” To which the boy slayer replies, “No, I’m killing boys. Boys are just placeholders; they come and they go.” But her superficiality and lack of guilt are indicative of the conditioning Jennifer has experienced as a female who is incessantly, even inappropriately, pursued by almost every man she encounters. In that way, Jennifer is not actually wrong about the male characters being portrayed as placeholders or archetypes.

Where Jennifer’s character is fully cinematically realized from internally tortured soul to demon of outward expression, it is her victims, like the football player and gangly e-boy, who are deliberately surface portrayals of any suburban male teen. Even her attackers, Low Shoulder, are makeshift band members desperate to make it big in the impossibly populated genre of indie. Most of the male characters in the movie are incredibly campy and fit a stereotype to show the boys fit into distinctly different categories. Of course they all treat Jennifer with the same objectifying demeanor. As such, each individual man, regardless of his unique characteristics, becomes a faceless placeholder to Jennifer.

When Needy tells Jennifer “You’re killing people!” Jennifer simply replies, “No, I’m killing boys.

Because Jennifer considers her male peers to be placeholders, she has little interest in pursuing actual relationships with the boys and more so hungers for power over them. Even though Jennifer calls the lead singer of Low Shoulder Nikolai “salty” before she and Needy leave, once they actually arrive at Melody Tavern, her first compliment is in regards to their status, “You can totally tell they’re from the city.”

Compared to the boys around her, Low Shoulder provides the femme fatale with a perceived challenge: an opportunity for Jennifer to truly see the extent of her sexual powers of persuasion. Being older and out-of-town, they existed outside of the midwestern bubble already dominated by the brunette. Had the value of her appearance not been relentlessly drilled into her mind by the patriarchy and its perception of women in the media, then perhaps Jennifer wouldn’t feel as though sexual conquests were her only means of empowerment over said male figures.

Still, Diablo Cody didn’t have Jennifer willingly follow Low Shoulder into their obviously creepy van to insinuate the teen was to blame for her own death. Having Jennifer killed by the hands of a man she is pursuing strategically mirrors female trauma often showcased in horror flicks and psychological thrillers. Cody then takes the dynamic and brings the unsuspecting damsel in distress back to life: no longer helpless, but a demon unequivocally powerful in a time ripe with the opportunity for righteous revenge.

Her demonic possession inspires and transfixes teen girls in the way Halo does for teen boys. Watching Jennifer lure a buff jock into the woods with her cunning sexuality to then tear him apart limb from limb did not scare me. In no way did her body physically impose upon the height and weight of this jock and in no way did he feel unsafe. Until she ripped his stomach out and exchanged her power of sexual prowess—something she’s always had—for her newfound power of physical strength. So forgive me if I enjoyed a single scene in which the female form was not the body desecrated beyond recognition. After all, a deeply empathetic connection to demonic Jennifer is not to be confused as a product arbitrarily hating men. Instead, seeing yourself trapped within the walls of Devil’s Kettle High School is a widespread response to what little value teenage girls are systematically offered.

Diablo Cody didn’t create a monster; she showed us the monster our pressure and projected desires create. In Fox’s words, all Jennifer did was “dare to be the same species as the people that victimized her.”♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox