We all know people who stay in relationships when they’re clearly unhappy. One of my girlfriends is still dating a guy who yelled at her because he found a stray piece of toast under their bed; he accused her of putting it there to spite him. Recently, an acquaintance was telling me that her husband isn’t a good person. “There must have been good times,” I said. She paused, then answered, “I’ll talk to you about it sometime when he isn’t sitting here.”

I’ve never met the writer and humorist David Sedaris or his boyfriend, painter Hugh Hamrick. But the more of Sedaris’s writing I read, no matter the ostensible topic, the more I can picture a toast inquisition, or one partner luxuriating in the thought of the other’s death, naturally happening in their home.

In Sedaris’s recent writing, Hamrick is described as someone who “hisses” rather than speaks. He’s portrayed more often negatively than positively, and comes in for harsher criticism than Sedaris’s siblings or even, sometimes, his alcoholic mother, who has probably risen in his estimation by virtue of being dead.

In “Why Aren’t You Laughing” (2017), his most recent New Yorker essay, about a vacation in Hawaii, Sedaris is nagged by Hamrick to get out of the house, even though Sedaris is quite obviously trying to process his mother’s disease by watching the reality TV show “Intervention.” In “The Perfect Fit” (2016), about shopping in Tokyo, Hamrick relentlessly criticizes what he considers Sedaris’s too-feminine fashion. These are the same criticisms strangers in Raleigh used to direct at Sedaris while shouting from passing cars, so it seems like something Hamrick should be sensitive about. Talking about one jacket, he tells Sedaris, “Maybe it’ll fit after you have your Adam’s apple shaved off.” Sedaris’s avant-garde Japanese clothes all sounded pretty cool to me, so maybe they weren’t the sole reasons for the insults.

I care about his relationship because Sedaris was one of my first role models for a kind of cozy gay domesticity, starting when I read his 2004 New Yorker essay “Old Faithful” in high school. Sedaris writes, “One boyfriend was all I could handle, all I wanted to handle, really, and while I found this to be perfectly natural, my friends saw it as a form of repression and came to view me as something of a puritan.” I’ve always felt the same way, and I’ve also been told several times that I’d outgrow my desire for monogamy, and always resented it. That made me emotionally invested in the success of Sedaris’s relationship.

When I was older and had already had a few boyfriends, and continued reading Sedaris’s essays, I started noticing a darker undercurrent in the writing about Hamrick. In “Old Faithful,” he writes about “the crippling panic I feel whenever Hugh gets spontaneous and suggests we go to a restaurant. ‘A restaurant? But what will we talk about?’”

Those lines haunted me during every awkward date I ever went on.

I kept searching until I found someone who didn’t mind telling the same stories on repeat and making inane jokes at dinner, so that we wouldn’t be silent like Sedaris and Hamrick, themselves fretting about their resemblance to couples in their seventies, “propped in [their] chairs like a pair of mummies.” (So far, my husband and I have managed to avoid that harrowing Pharaoh fate. But it’s only been five years.)

In those lines, Sedaris is certainly giving us an unflinching, funny look at the nature of monogamy. But I’m worried that there might be more to it than that. Consider his 2015 essay “A Modest Proposal.” Sedaris wants to get married, not to have “the government sanction [his] relationship,” but to save money on taxes. “I’m not marrying you,” Hamrick says. They argue until Hamrick grudgingly agrees. The next evening, they act like the whole conversation never happened. They “retreated to different parts of the house, engaged, I suppose.” I don’t want to indulge in kitchen psychology about positive communication herebut surely an accepted marriage proposal deserves at least a friendly handshake?

Whatever the topic of Sedaris’s essayshe’s covered poisonous snakes, 400-year-old embalmed heads, French dentists, and truly terrifying things, like the UK Border Agencyhis bickering with Hamrick is a constant theme. I find this weirdly fascinating, a little like the way Sedaris feels about farts. In “Company Man” (2013), after Sedaris’s houseguests leave, he writes, “We have our share of fights, the type that can start with a misplaced sock and suddenly be about everything. ‘I haven’t liked you since 2002,” [Hamrick] hissed during a recent argument over which airport security line was moving fastest.” In “What We Did at the Beach” (2015), a moving tribute to Sedaris’s father, he makes time to complain about his boyfriend: “Hugh calls and schedules an appointment regarding something I know nothing about. Then he leaves for God knows where and I’m left to explain what I don’t understand.” By “Untamed” (2016), a certain resignation has set it. Sedaris and Hamrick get two cats, and “from the day they entered our lives until the day they died Hugh and I fought over how to feed and care for them.” (My husband and I carefully tamp down our fights in order not to traumatize our cat.)

In Sedaris’s first volume of diaries, Theft by Finding, which was published in 2017 and covers his life from 1977 to 2002, Hamrick does earn some romantic praise. “This spring I am, if I’m not mistaken, in love,” Sedaris writes in March of 1991. Ten years later, the vibe is more complacent, as the couple sits at dinner and listens to Joni Mitchell, each silently mourning the more passionate longings of youth. It unsettles me that Hamrick’s remark about 2002, seemingly tossed off at random, actually lines up with my reading, where the first signs of trouble in their relationship appear in 2004 and have since intensified.

Of course, there are good artistic reasons to emphasize the negative. It gives his work its bite. In “What We Did at the Beach,” Hamrick asks Sedaris, “Why do you choose to remember the positive over the negative?” Sedaris wonders, “Does choice even come into it? Is it my fault that the good times fade to nothing while the bad ones burn forever bright? Memory aside, the negative just makes for a better story. Happiness is harder to put into words.” But Sedaris ends the piece on an uplifting note, a beautiful moment of his father listening contentedly to jazz. We know he can do it. When it comes to Hamrick, it almost seems like he chooses not to. (In his recent New Yorker essays, I found two exceptions. He calls Hamrick his “handsome longtime boyfriend” in one, and in the other marvels at his skill in dealing with bureaucracies. Rather minimalistic compliments.)

This worries me because I obviously can’t predict the future, so I’m trying to read it; to tease out what my destiny is, through people who’ve described their destinies before. Anti-monogamists would interpret Sedaris’s recent work by saying is that regardless of how great a relationship may be, there is no escape from bickering about airport security lines with my husband in old age. I prefer to think that he and Hamrick just aren’t very happy. In “Understanding Owls” (2012), Sedaris writes, “Hugh and I don’t notice the same things. That’s how he can be with me.” He can, but should he?

At a reading last month, an audience member asked Sedaris how Hugh was doing. In response, he briefly fooled the audience into thinking they had broken up. Then “he flashed a sunny grin,” writes Sarah Lyall of the Times. “‘Just kidding!’” I’m not sure he was.

David Sedaris’s new book, Calypso, will be published on May 29.

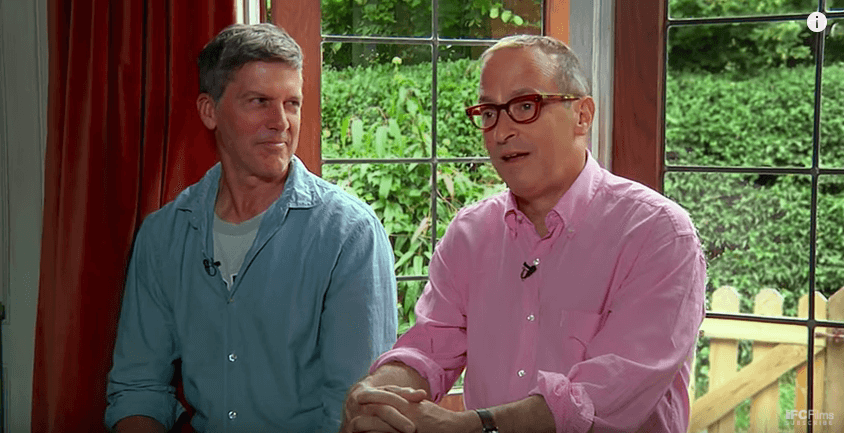

Images via IFC Films/YouTube

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox