“I look like a Pepsi girl!”

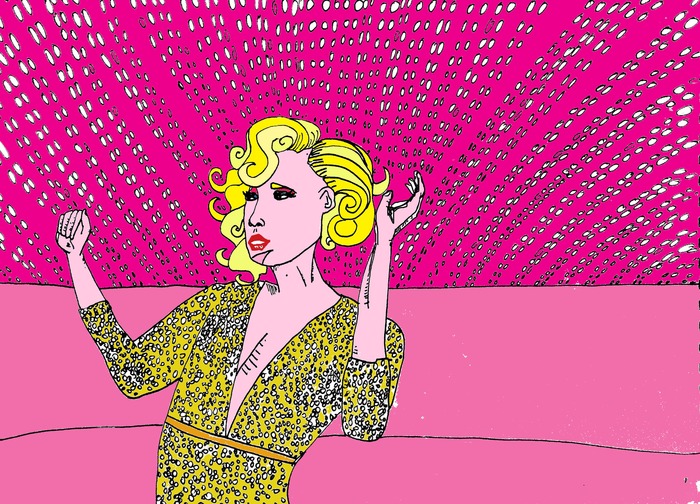

Onur Gokcek finishes applying the last touches of his makeup, and he looks up. There are red and blue glitter wings around his eyes, and his hair is done in tight curls that took hours.

“Glitter can hide anything,” he says with a wink.

He pulls on a fur coat over a gold glitter bodysuit, and when he emerges onto the street, it is as his drag persona, Cake Mosque. Gokcek catches a cab to Love, a popular gay club in central Istanbul. He arrives around 2:30am and the floor is packed. Men are pressed close to each otherit’s almost impossible to move and a throbbing bass shudders through the entire building. People are kissing next to the stage, and above it all sways Cake Mosque dressed in gold sequins. She throws her head back, dancing to the music.

Cake performs with another queen and they share a small sliver of the stage with a DJ booth. There is hardly any room for them to move, but they still twist and turn to the music. In between sets they mingle, talking to clubbers and working the crowd.

A few days later, the governor of Turkey’s capital Ankara would ban all public activities with LGBTQ content. That week, a district in Istanbul cancels an LGBTQ film festival.

Two hours away from central Istanbul, another queen gets ready. As LouLou Androgen, Ercan Topcu is one of Istanbul’s original queens. He started when he was 16 years old in the 1990s, when there were only two other queens in the entire city.

“This is my life,” he tells INTO, “the show, the stage, and being a drag queen.”

Topcu performs at X-Large, a lavish mega-club inside a building the size of a warehouse. Its stage is hugeit has two levels, a curtain, lights, and rigging for acrobatics. Before the show, Topcu shows me an article on his phone about the Istanbul ban, shaking his head.

“This government doesn’t want gays anywhereeverywhere we are banned now,” Topcu says. “Gay people are banned,but we have shows, clubs, everything.”

Backstage at X-Large, the rooms are overflowing with feathers and sequins; dancers wander in out as they prepare for the show. It’s comfortable. One of the women is celebrating her birthday, and the other dancers bought her a cake and presents. Topcu drinks a cocktail as he puts the finishing touches on his makeup.

In Topcu’s opening act, he has back-up dancers, choreography, and matching costumes. He is one of at least three queens who perform that night. Their performances are sexual and deeply queer. A young queen vogues across the bar in a leather harness. Another gives a stunning matador-inspired performance featuring men in pleather bodysuits wearing jewel-encrusted bull masks.

Still, it is hard for it not to feel like a bubble. In Turkey, 78 percent of the population say they reject homosexuality, according to a 2013 Pew study. Pride in Istanbul has been banned for three years in a row.

“I’m not surprised by anything that’s happening in Turkey anymore,” says Louis Fishman, a professor at Brooklyn College who has researched LGBTQ issues in Turkey. “It is in line with what has been happening to civil organizations. They don’t want any group speaking out of key.”

Since an attempted coup against Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan in 2016, there has been a massive crackdown on anyone even tangentially in opposition to the conservative government. Purges throughout civil society, education, media, and rights organizations have resulted in over 47,000 arrests in the past year.

Fishman thinks that the moves against LGBTQ events are a continuation of this crackdown and set a dangerous precedent for the future.

“Now they think they have the power to do everything,” says Gokcek. “You can feel it.” He says that going out in the street in feminine clothes is something he thinks twice about now. “One time I was looking in the mirror, I realized I was closed to myself. I didn’t want to wear something colorful to draw attention to myself, I was always wearing black.”

Drag falls into a strange place in this crackdown. On the one hand, it is one of the most visible expressions of queer art in Turkey. On the other hand, because of its fantastic and theatrical nature, it appeals even to conservatives who would never openly support the LGBTQ community.

Gokcek used to work a restaurant called Cahide Muzikhol, which is famous for its drag shows and for catering to the upper crust. The performances there are slick with choreography, costume changes, fire-dancers, trapeze artists, and at one point, a live snake. In the highlight of one dance, one of the queen’s bustiers starts to shoot off sparks into the crowd. The effect is incredible. But at the same time, you cannot help but feel a dissonance.

At Love, Gokcek was performing for queer men who were looking at him with desire. In the restaurant, the audience sees the queens as exotic oddities.

This does not bother Ahsen Gonulce, a queen who has been working at Cahide Muzikhol for 12 years and is the grand dame of the restaurant. He takes a perverse pleasure in making his living off people who in other settings might profess to hate him for his sexuality.

“If you really work then those who are angry and hate you, they come here to applaud you,” he says after the show.

This is not something that is confined to Cahide Muzikhol. One of Turkey’s biggest celebrities is Bülent Ersoy, a transgender woman and performer known as “The Diva.” Even Erdogan has publically invited her to dine with him. But she has notoriously kept silent on LGBTQ rights and politics.

Her silence infuriates Gokcek, who has continued going to Pride despite the government bans.

“Last year, when Pride came at the same time as Ramadan, there was an Iftar [the dinner to break fast during Ramadan] by Erdogan and all the celebrity actors and singers went to his place,” Gokcek says. “It was the same Sunday as the Trans Pride walk and Bülent went to Erdogan’s house for Iftar.”

“It’s so stupid,” he adds. “What the fuck?”

The same day that Ersoy was dining with Erdogan, riot police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at the march for transgender pride.

Gonulce laughs when this is brought up. “It’s so funny because four weeks ago, [Erdogan’s] daughters and her friends were here at this club. Last year as well,” he says. “His parents also come sometimes.”

He explains that various members of Erdogan’s family including his daughters and his parents have visited the club to see the show. He starts smoking a cigarette and his voice drips in disdain. “Erdogan is Muslim, but Muslim for who? For play.”

The drag scene is further complicated by the fact that even within the gay community, drag shows are not always welcoming to everyone. Gay clubs have a history of discrimination against men who crossdress and even moreso against transgender women. Gokcek says it is only recently that clubs have started to allow trans women to enter the clubs and some clubs still bar their entrance.

“Love, the place where I work,” he says. “It’s not good to say it for the interview, but I have to be honestif you’re not working there, they don’t let transgender people in.” But he adds that gay clubs are slowly becoming less discriminatory, even Love is finally allowing some trans people entrance.

Still it is difficult for trans women to find acceptance. Gokcek remembers multiple instances where even fellow drag queens were transphobic. One time he was even chastised by a fellow queen for wearing lipstick outside of a show. Even Gonulce, who works with a trans fire dancer at Cahide Muzikhol and says he is not transphobic, will make comments disparaging trans sex workers as “fake” and saying they should get real work.

Gokcek says the queer community in Istanbul is very divided, transgender people go to transgender spaces, gay men go to gay spaces and lesbian women go to lesbian spaces. “If we want to do something, we have to do it all together,” he says. Gokcek wants to be an active part of creating unity. He hosts and DJs parties that are open to queer people of all genders and backgrounds.

“My parties are for queers,” he says. “Queers are coming to my party. You can do whatever you want and you can come however you likeit doesn’t matter.”

But even this hypocritical side of the drag scene shows its breadth of its diversity in Istanbul. It is present in the queer clubs, it is present in the mega clubs like X-Large, and it is present in the places where Istanbul’s most powerful people go to enjoy themselves. It is far from the ’90s, when Topcu knew no one like himself and had to figure out the fundamentals of drag without guidance.

“People all over the world were different then,” Topcu says. “Now we have the internet. People can see gay life and gay pride. Young gays are watching RuPaul’s shows and young gay people on YouTube. When I was 16 years old, we didn’t have that.”

Gokcek is an example of that visibility. A few years ago, he starred in a Turkish music video that went viral and showed him in and out of drag. His Instagram account is followed by thousands of people.

When Topcu first began doing drag, he couldn’t even find a shop that made high heels that would support him. Now he is sitting in a dressing room that he shares with three other queens. Hundreds of people are waiting outside to see him perform, and there are at least four other drag shows happening that same night.

Drag is alive and thriving in Turkey and it won’t go away, no matter how many bans threaten its extinction.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox