I first came across Mel Odom’s work while lost in a sea of cocks on canvas at the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles.

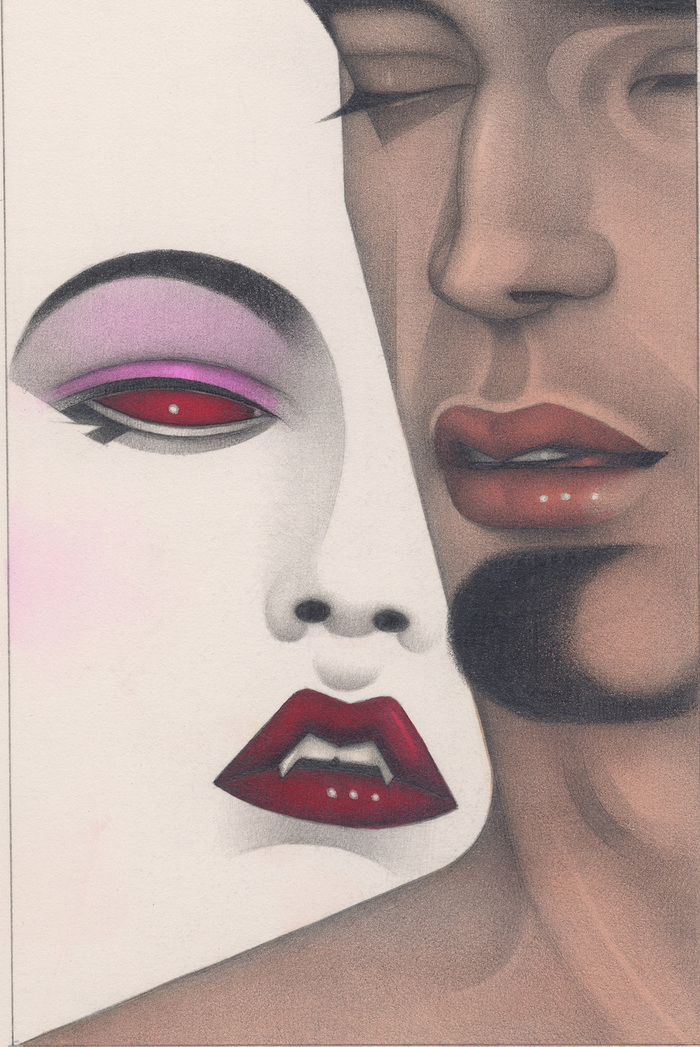

The piece on display, Arrangement, featured two sphinxlike men in a sort of Rubin’s vase-style composition that merged their chiseled faces into one. Despite its glaring lack of phallic adornment, it owned the roomand I wanted to own it.

The print was blown up from a 1979 cover of Blueboy, the seminal gay softcore/lifestyle zine that ran from the mid-’70s until the internet killed it in the mid-’00s. Odom’s homoerotic illustrations for sexy mags like Blueboy and, later, Playboy, anticipated the type of graphic deco revival that would come to define ‘80s new wave. Duran Duran tapped Patrick Nagel for their album covers; Erasure or Bronksi Beat would have gone to Mel Odom.

Odom eventually left behind the labor-intensive style that earned him “Illustrator of the Year” from Playboy in 1980 for other pursuitshand-painted masks, a line of dolls inspired by Hollywood’s golden age, lush oil paintings of Civil War-era dollsbut he’s never stopped creating beautiful things.

Today he enjoys cult status among a new generation of queer creators who have found inspiration in his work (stylist Nicola Formichetti among them),while continuing to create objects of desire across a variety of mediums.

In a recent email conversation, Odom and I discussed his journey from small-town North Carolina to the pages of Playboy, his experience living in New York at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and the day he had his picture taken by Robert Mapplethorpe.

You knew from a very early age that you wanted to be an artist. How did you get started?

I always drew. I picked up a crayon and started scribbling in my brother’s books when I was two or three. I have the scribbled-in book to prove it. I clearly wasn’t trying to deface the book, I was just trying to draw. My color sense for these scribbles was unerring.

I didn’t think about drawing at all, it was unconscious, just who I was and what I did. My parents recognized this and made sure I had plenty of crayons and paper to draw with. I think what impressed them was how many hours I would spend just sitting and drawingwithout anyone asking me to. I have most of my childhood drawings from age four upward. My mother saved and dated many of them and many years later gave them to me in a Home Town Dress Shop box. It’s the best thing anyone ever gave me.

What were your biggest creative influences growing up?

Probably magazines and cartoons. I grew up in a very small town in North Carolina, population 4000. There weren’t any museums or galleries to go to. My sources of inspiration were the magazines my parents got and the cartoons and movies I watched on TV. Silly Symphony was on TV every day on The Mickey Mouse Show and I lived to see those. These and many other cartoons still have the power to thrill me. I had picture books as well, but magazines were more glamorous. They had movie stars and models. Old cartoons had fairies and mermaids. These were the things I drew.

Did your sexuality – whether consciously or subconsciously – shape your artistic development at all?

Sure, I think it’s inevitable. Most little boys aren’t doing drawings of model Suzy Parker and Cinderella. I was a part-time, classic little Southern sissy boy, playing with dolls and having as many girl friends as boy friends. But my two best guy friends were the neighborhood hell raisers so I was also building forts and climbing trees and playing in the woods. I was pretty well-rounded in that respect.

Who you are always comes through in your art, one way or another. My sexuality expressed itself by my feminine-self dominating my creative works. I LOVED dolls, rag dolls, paper dolls, anything that looked like a doll. My grandmother had famously made rag dolls during WW2, so I grew up with dolls being given me. I literally thought they were magic, probably supernatural. I think I associated their scale with fairies, which I totally believed in. As a child I lived in a fantasy world a lot of the time, more than people realized. I believed in practically everything.

You moved to New York City in 1975 and quickly found success as a commercial illustrator for publications like Viva, Blueboy, and Playboy. What was it like living and working in the city in those days?

It was pretty cool. I think I happened to be in the right place at the right time. I moved to NYC already having a $300 freelance job to do, which quickly led to more work. It was for Viva magazine, a woman’s magazine with male nudes in it. This first drawing was for a sexual fantasy editorial and I included an erect penis in the image.

My odd style of drawing, plus the nerve of me putting the penis on the page, attracted a lot of attention. I got offers from other erotic magazines, including Blueboy. Once I started working for Blueboy I was released from any possibility of censorship of eroticism in my work, and did quite a few of my most important drawings for them. They weren’t pornographic so much as erotic, with faces and gestures expressing passionate emotion rather than just sex. They were sexual thoughvery much sobut they had an extra dimension beyond the physical.

My cover for Blueboy is one of my most important drawings. It’s just two men’s faces together but manages to convey much more, and be very much an emblem for that period. Blueboy led to Playboy, which led to TIME Magazine. It wasn’t a conscious climb, it just happened. I worked freelance for Playboy for 17 years and did many of my best drawings for them. They were very open and not at all afraid of the homoerotic underpinnings of some of the drawings. I loved working for them.

You’ve mentioned having a lot of artistic freedom at those publications. Was the overt sexuality of your work – or your own sexuality – ever an issue for you professionally?

Not really, people came to me for that. I became the go-to guy for that sort of thing. Once I was asked to draw a shoe for a traditional ladies magazine, Redbook I think, because “I could make anything look sexy”. I had a lady agent who I believe let me go as a client because she was uncomfortable with the eroticism in my work. She never said it but I always felt it.

You were photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe. How did that come about?

I was having a book of my drawing published in Japan and wanted a wonderful author’s photo for it. I wrote three photographers: Mapplethorpe, Francesco Scavullo, and Richard Avedon. I never heard back from Scavullo, got a lovely but declining note back from Avedon, and a yes from Robert Mapplethorpe. I was SO excited he was willing to do it.

I borrowed a beautiful tux from a friend and brought a dozen red roses to the shoot, hoping he would want to use them in the portrait. He was great, easy to work with, and the photo he took was exactly what I wanted. I figured I would aim high with the photographers I asked and see what happened. I advise working that way.

You lived through the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. How did that affect you and your work?

It started for me in 1983 when my first NYC boyfriend died of a nameless disease, later to be labeled AIDS. I was stricken with an overload of grief and fear. I had fallen in love just in time to lose it, and probably my life as well. By all scientific evidence it would be just a matter of time before I followed him.

My work saved me. It gave me a constructive focus that kept me from just self-destructing. My drawings became very geometric and madly controlled in order to balance the sense of having absolutely no control over what was going on around me and in me. I lost two-thirds of my friends during that time, people my age who were no less worthy of living than I was. The grief was overwhelming and the surreal sense of an invisible battle that was happening all around me just pushed me further into myself and my work. Art saved me from the fear by giving it an expression.

My pencil drawings on vellum paper from that period are where much of my most private work happened, with drawings named “Sleepless Nights” and “Lies From George.” I wanted to leave behind a record both beautiful and true. I thought I’d be leaving soon, so there was a sense of immediacy.

How has the attitude towards queer art changed over the years from when you started to today?

For a while I shunned the label “queer artist.” I didn’t want to be limited by what that implied. Over the years though I’ve realized that everyone is bound by the time in which they live, and I happened to live during a plague that decimated the creative/artistic gay community.

Each death of a friend was a nudge to the ribs that my time was coming. I think this is expressed through many of my drawings, a sense of the immediate being the only sure thing. I wear the label of gay artist more easily now, knowing that the things I leave behind document an important time in history.

I think queer art has become more overtly political by necessity. Many of our current political leaders would have us disappear completely without our constant reminders that we are foremost among the souls who record and create our culture. Now is not a time to be silent. Queer work has gained content by the world that has happened around it.

Dolls feature prominently in your work – you created a line of dolls in the early ‘90s, and more recently you’ve been doing gorgeous paintings of vintage dolls. What draws you to working with dolls?

I’ve loved dolls for as long as I can remember. They are among my earliest memories. I inherited dolls from my older girl cousins, so I played with them from the start. I think that loving dolls as a child was my first experience of wanting something that my sex wasn’t supposed to want. Being told that something isn’t for you doesn’t make you want it any lessprobably more. It just drives it inward where it really counts. I think playing with dolls was my first sense of being a sexual outlaw.

The doll that I created, Gene Marshall, was an expression of what I thought of as the best of myself, an optimism and sense of wonder. I created Gene primarily because my best friend Brian Scott Carr was dying of AIDS and I desperately needed something new and challenging to focus on, to help me get through the trials of that. I’d seen many deaths by then, and knew too well what he was going to go through.

His hospital was three blocks from the sculptor’s studio. I’d visit him in the hospital and then go work with the sculptor and gradually come out of the depressed funk I’d come there with. Gene was my escape into a fantasy world of Hollywood glamor and beauty. No death, no disease, just a climb to a climax. I wanted her to be that for others as well, to help them with whatever they were going through. I think I accomplished that.

The paintings of the Civil War dolls were an approximately ten-year mourning period for me. My second parent had died, my mother, and I was left with so many goodbyes that I needed to express somehow before I could get past them. These dolls, these pale, brittle, survivors of the Civil War were a perfect analogy of how I felt.

I marveled at how something so fragile had survived so violent and tragic an era. I couldn’t bring myself to paint portraits of all the people I’d lost, so these china dolls stood in as totems for them. There are many death symbols in these paintings, cartoon skeletons and mourning jewelry. These are my farewell to much and many that I’ve loved.

After these paintings I did another group of paintings of mid-century dolls that became much brighter in color and joyful. I think this was my coming out of a depression of sorts. Not that I’m planning on it, but If I were to drop dead tomorrow I’d be satisfied with all these doll paintings as my final word. They’re very personal.

Who are some of your favorite artists/creators today?

I love so many people’s work it’s impossible to list. For me to love someone’s work, I have to feel they’re playing for keeps with it. Any art too glib or corporate doesn’t speak to me. I like representational art as well, something I can attach some experience or feeling to. I fear I’m too literal in that respect. There are abstract paintings I love but I’m guessing it’s because of something I infer from the abstraction. I’m about beauty in all its forms.

The art world is a tough one to make a living in, and frequently the people who produce the most vital art are not especially tough people. These people can be actors, musicians, any kind of artist. So you have a lot of crash and burn victims among the arts, people whose vulnerability fuels their work and fails to protect them from the various sacrifices of producing it. I like art that I think mattered to the artist who created it. I love Picasso’s work, I love the Pre-Raphaelites, I love Ed Rucha’s work. I could go on for a whole page with the names of artists whose work I love.

What’s next for you?

Well right now I’m organizing my studio. I work hard on things for a period and let the order slide. Then you have to pull it back together just to be able to continue. In this reorganization I’ve recently found dozens of sketches and drawings that I haven’t seen in years and have, in many cases, totally forgotten about. One is a self portrait from the late 1980s. I’m trying to decide if there’s anything here I need to re-visit or resume.

It’s very fun to find forgotten drawings and manage to be impressed with them. I can like things in hindsight that I might not at the time I create them. Sometimes a difficult ‘birth’ colors my enjoyment of the finished piece. I feel at the moment that I’m in some sort of transition. I want another obsession in my work, something I just can’t get enough of. That’s when I’m the happiest and most focused.

Where can people see more of your work?

I’m with a lovely gallery in London right now, Laura Bartlett Gallery, and have a few paintings in NYC at the Georges Berges Gallery. My website where I can be reached is www.mel-odom.com. Thanks for asking interesting questions. X.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox