“I’ll go back to brunch motherfucker, I don’t care.” The audience laughs as Anthony Bourdain adjusts himself on stage at SXSW in March of 2016. Delivering lines like this–filled with irreverence and honestly what Bourdain excelled at. It’s what made me fall in love with him as a recently-turned-vegetarian teenager in the mid-aughts, poring over page after page of his words on sticky summer days in the suburbs of Toronto. My dad passed me one of Bourdain’s books to school me on his culinary crush’s opinions of vegetarians. My flatulence was legendary amongst family and friends and my father was convinced that my gaseous state was caused by my chosen diet. (We would later find out that the farts were largely due to undiagnosed Celiac disease, but I’m sure that chickpeas also played a part.)

Even though I didn’t agree with Bourdain’s take on my chosen diet (what self-important 16-year-old would?) I kept reading his books and I kept watching his shows. I figured, if my dad liked this guy, there must be something to it (my dad has never steered me wrong about a book or a band.) But also because dude seemed legit.

Rather than his delight in outré cuisine and off-beat tourist destinations, Bourdain’s deep interest in humanity was the beating pulse behind Parts Unknown.

Bourdain had a television career that could be considered successful even before CNN’s Parts Unknown entered into the public consciousness. It was the series that brought his personality and his work to a wider audience. The first episode of this new series was not what I expected —a compassionate meditation on the people’s plight for democracy in Myanmar. —and I became quickly aware that this would be a series different from A Cook’s Tour, No Reservations, and The Layover. Rather than his delight in outré cuisine and off-beat tourist destinations, Bourdain’s deep interest in humanity was the beating pulse behind the series. And responsible for the pulse was the heart of the show: the conversations Bourdain had with “mostly pretty nice people doing the best they can under very, very difficult conditions.”

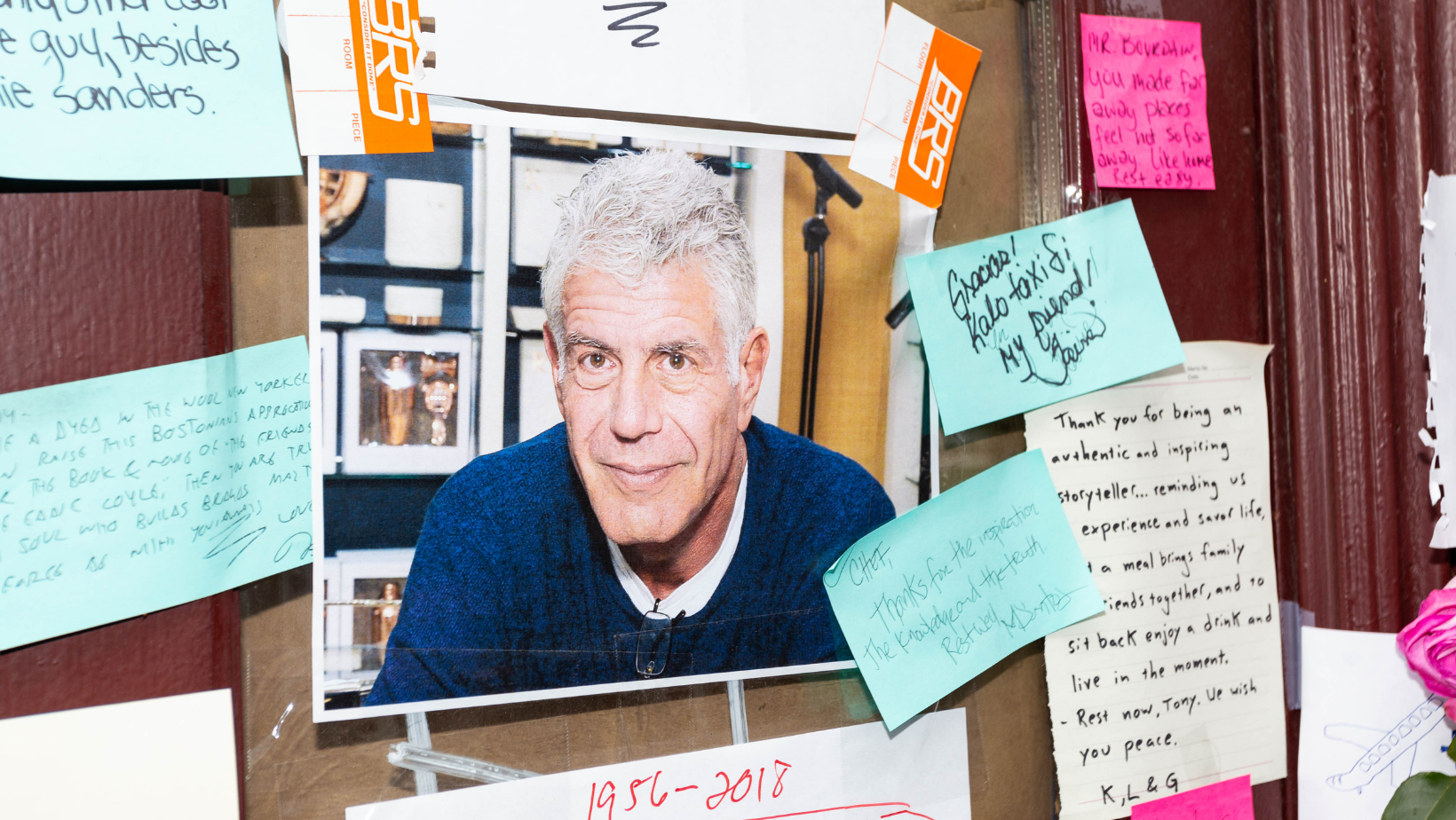

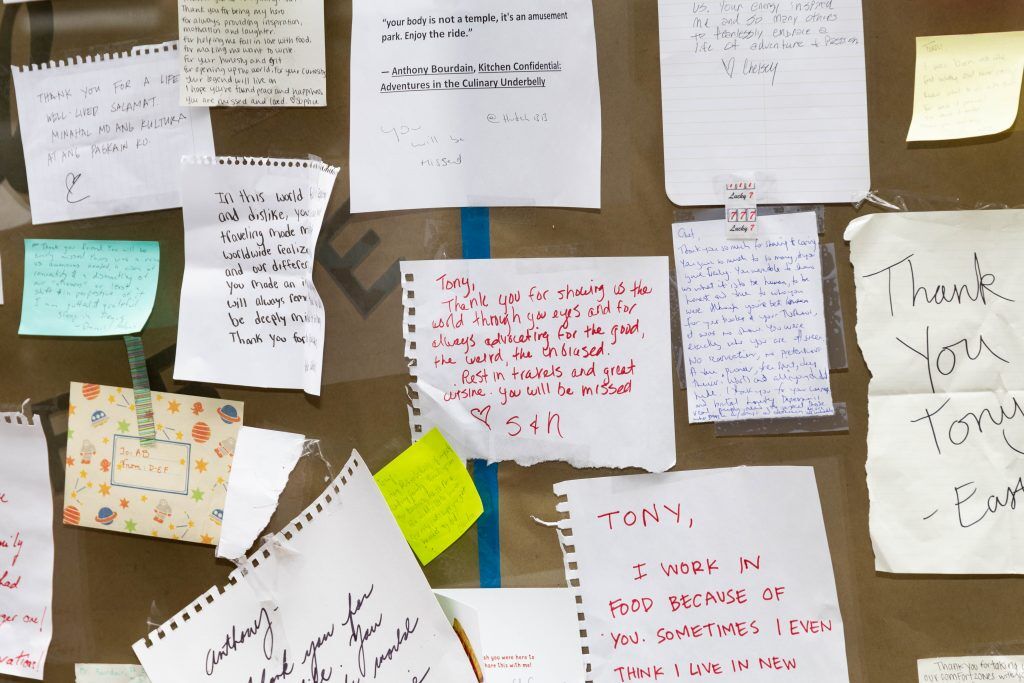

When Parts Unknown premiered in 2013, I was living in New York completing my Masters degree in a field I didn’t much care for (sorry, Mom) and in a relationship that I very much wanted to end (and yet wouldn’t for another three years. Sorry, D.) Shortly before moving back to Canada, I found myself on a rooftop in Greenpoint drinking a bourbon iced tea slushy. In the company of one of my best friends who flew in from Toronto that weekend, I found myself yelling at the skyline across the East River, “Let’s Anthony Bourdain this shit!” At the time, this proclamation came from that kind of carpe- diem- seize- the- day- yolo bullshit attitude that only an unmedicated hypomanic 25 year old can have. But now, nearly three years after Bourdain’s death, that phrase takes on a new meaning for me, this time as a rallying cry for embracing vulnerability.

Let’s be clear: Bourdain was a vulnerable guy. I mean, it doesn’t get much more vulnerable than confessing your gravest sins to the world in a public fashion. Which is exactly what he did. Repeatedly. Over multiple memoirs. He even titled one “Nasty Bits.” Bourdain was upfront about his personal foibles, which included his struggles with substance use disorder. To open up about challenges related to mental illness isn’t easy. As someone who continues to work on understanding her own relationships to substance use, mental illness, and uh, just generally being a toxic person because I didn’t know another way of being, I can tell you firsthand that it takes a lot of work, courage, and vulnerability to move forward with recovery privately. And I can only imagine that it takes a hell of a lot more work, courage, and vulnerability to share your recovery publicly like Bourdain did.

It was this vulnerability and courage: to own up to his past choices; to move forward without judgment for self and others; and to approach life with an insatiable curiosity, that made him charming, disarming, and infectious. It was obvious that when he sat down to share a meal with someone, anyone—whether his old dear friend chef Eric Ripert, a member of Hezbollah, or President Obama—Bourdain was fully and completely present. His open presence, with its manifesting in his “this is who I am, take me as I am” demeanor, granted his dinner partners the ability to feel comfortable with their vulnerability, too; it’s human nature to want to match the manners of others.

It was this vulnerability and courage: to own up to his past choices; to move forward without judgment for self and others; and to approach life with an insatiable curiosity, that made him charming, disarming, and infectious.

Part of me wonders if he knew his superpower was putting people at ease with his authenticity. He certainly recognized that sharing a meal with another person—particularly if that person is a tall n above-average in height privileged older white guy from Jersey who works in television—can make one feel vulnerable. It’s impossible to know if he recognized the role that he played in creating space for others out of their protective shells, but he certainly knew that a shared meal allows for powerful questions to be asked and for powerful conversations to be had. In an interview with the CBC’s Fifth Estate, Bourdain elucidates that when you share a meal with someone, “they let their guard down when they talk to you. You see them at their most vulnerable and revealing in a lot of ways … if you’re going to intersect anywhere, it’s going to be over food … I’ve gotten along with people everywhere in this world and heard some incredible stories largely because I sit down without an agenda and just ask a very simple question: “What’s for dinner? What makes you happy?”

Part of me wonders if he knew his superpower was putting people at ease with his authenticity.

Although I’m not yet sure what’s for dinner tonight, I am sure of this: what makes me happy is seeing people live radically authentic lives by owning their vulnerability and making space for others to do the same. Bourdain taught me that by showing up wholly as I am, as flawed as I am, I allow for others to show up wholly as they are, as flawed as they are. That’s what “Let’s Anthony Bourdain this shit” means to me now: being there for each other in tender moments with an open heart and an open mind. “Let’s Anthony Bourdain this shit” gives us the opportunity to recognize the humanity in each other and to recognize what we owe to each other. At the end of the day, creating connection and fostering understanding doesn’t have to be hard. As the late, great Bourdain said best: “To sit down with people and to eat with them, to express a little interest in their food and what makes them happy, it may not be the answer to world peace but it is a start.” Even if your next meal doesn’t feel like a start to world peace, may it be a start to finding inner peace through embracing your own nasty bits.♦

Courtney “CK” Kurysh is a femme poet, writer, and coach who writes about big feelings. She lives on a tree-lined street in Toronto with her partner and their two cats.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox