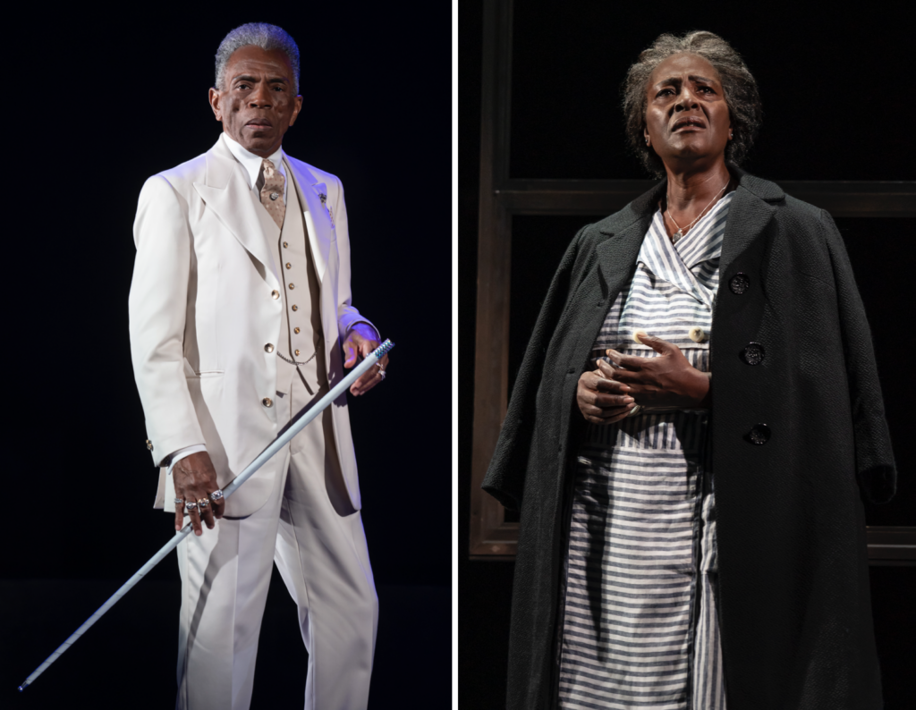

(l to r) McKinley Belcher III, Sharon D Clarke and André De Shields, now appearing in the Broadway revival of ‘Death of a Salesman.’ Photo by Grier for INTO.

Attention must be paid.

Linda Loman, Death of a Salesman

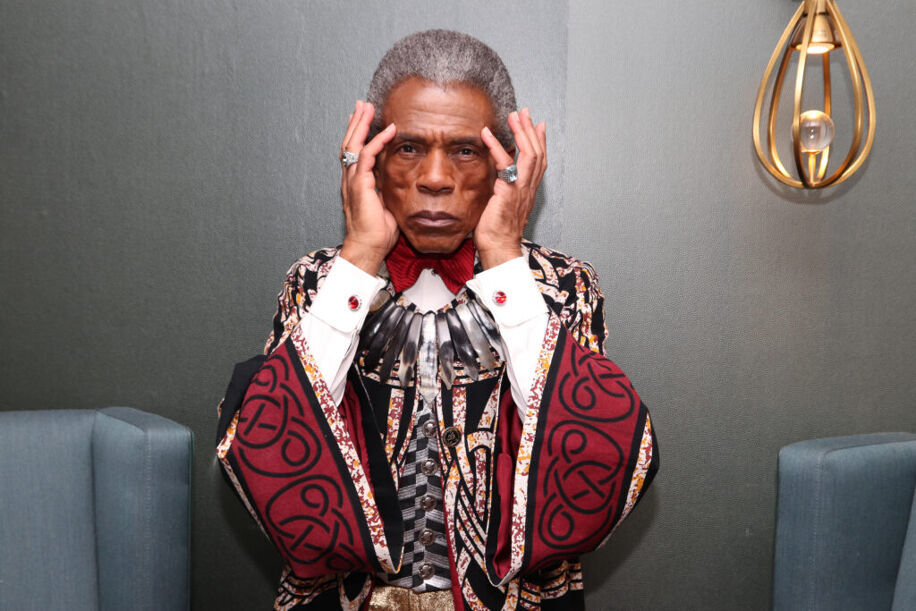

The legend enters first. Wearing a muted purple suit with a crisp pocket square and clutching a weathered copy of Arthur Miller’s famous play, André De Shields doesn’t merely walk. He transcends space.

Sharon D Clarke, nominated for a Tony Award last season for her searing portrayal of a maid in 1963 Louisiana in Caroline, or Change, arrives next. She sports a silver ankh, an ancient Egyptian symbol of eternal life. By the time we convene in the Hudson Theatre’s Ambassadors Lounge, McKinley Belcher III, alarmingly affable as he is handsome, has joined the entourage. The trifecta is now complete.

The three actors have gathered to discuss a history-making moment: the first time Broadway audiences have seen Death of a Salesman‘s Loman family portrayed as African American. They also represent three generations of the LGBTQ+ community, whose identities bring further nuance to director Miranda Cromwell’s re-examination of the classic text.

Related: The Great Migration Informs a Stark and Stunning ‘Death of a Salesman’

Set in 1949, the new production positions the Loman family as part of the second wave of the Great Migration, which saw hundreds of thousands of Black Southerners migrate to New York City. Brown v. Board of Education wouldn’t end racial segregation in public schools for another five years, and it would be nearly two more decades before the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.

De Shields has lived through all of it. Clarke has also experienced racism. The daughter of Jamaican immigrants who settled in North London in the 1950s, Clarke told Vogue that a neighbor once asked her what it was like to live in a house for the first time. Belcher, who intended to study law but got permanently sidetracked after starring in a college production and then earned a full scholarship to USC School of Dramatic Arts, says of the play, “It never occurred to me that it could be a Black family.”

Yet here they are, sitting among polished brass and velvet curtains in one of Broadway’s most legendary theaters. INTO editor Joshua S. Mackey sat with the actors for an intimate conversation about their experiences working on the play, how queerness can inform classic texts, and the power of intergenerational relationships onstage and off.

Three Generations of Black LGBTQ+ Visibility

The casual observer would think that the three actors were blood relatives. An unspoken familiarity hovers in the air — an affectionate arm around the shoulder or hand on the knee conveys a palpable knowingness of lived experiences. De Shields made his Broadway debut nearly 50 years ago. For Belcher III, it was the 2020 Tony-winning production of A Soldier’s Play. Clarke, a veteran of the London stage who appeared opposite Wendell Pierce in the West End production, reprises her role. But their credits only begin to tell their story.

Clarke: It’s just about sharing and going, “We’re here. We’ve been able to do what we have been doing, being ourselves and being able to pass on that baton and say, “Run with it, baby.” It is all possible. It is all doable. Just enjoy being who you are, where you are on Broadway in this phenomenal play, looking through this lens, and being able to stand up in interviews and go, “This is me and my partner.”

I think that’s the best way to lead by example, to just be, and to just live it.

Belcher III: There’s something about acknowledging the fact that both of them have been doing this for a while, and they’ve been authentically and fiercely themselves.

Now it’s en vogue to be queer and be your full self. But the fact that André and Sharon have been living their lives fully, even when that wasn’t convenient … The fact that they were being encouraged to hide themselves and they still chose to say, “No, this is who I am. And not only “This is who I am, and I can show up fully in this work and shine bright.”

It helps me be able to shine brighter, just standing next to them, knowing that they’ve been doing it for so long and doing it their way.

De Shields: I’m particularly intrigued by this opportunity to be performing as Ben, the older brother of Willy Loman, because the history of this play if you’re doing the right research, it’s also the history of the queer individual in America. Now, as the elder in the company, I recall when the term “gay” was appropriated from the Great American Songbook. It meant to be cavalier, to be without a care in the world. Then, what we call Stonewall happened, and the word took on another meaning altogether, still segregating the Afro-queer individual from the mainstream.

The point I’m making is through all of those changes, it has always been our white counterpart who was defining who we are, even as inclusive as the word gay is. This distinguishes us, the melanin in our skin. So we have to be soldiers. We have to raise the bar, and we have to remind people that the fear, the intimidation, and the biases that you are experiencing, you must stop projecting [them] onto us. They’re your insecurities that you have to deal with. And now that we have this term, Afrofuturism, which I think is the most inclusive of all those terms, I have no use for the term gay except to say, “Without a care in the world.”

Redefining the Theater Experience for a New Generation

There have been five previous Broadway productions of Death of Salesman, garnering Tony Awards and other accolades for its lead actors from Dustin Hoffman (1984) to Brian Dennehy (1999). But the dismantling of the American Dream has often been viewed through a white gaze. In fact, Broadway itself is facing its own racial reckoning. The Black Theatre Coalition, The Broadway League’s Black to Broadway, and Black Out (conceived by Jeremy O. Harris) are recent initiatives to recalibrate Broadway to be more inclusive for both artists and audiences.

“The mission of the theater, after all, is to change,” said playwright Miller (1915-2005). “To raise the consciousness of people to human possibilities.” More than 70 years since it first premiered on Broadway, this production of Death of a Salesman fulfills that vision, enabling more diverse audiences to see their own histories and experiences reflected onstage.

Belcher III: I read [Death of a Salesman] when I was in high school, and it boggles my mind that at 14, I remember being impacted, especially by Biff, because I have a complicated relationship with my dad. But it never occurred to me that it could be a Black family. And the fact that we’re doing this in this way, and students will come see this, and their first experience of this play is experiencing it as a Black family, and in some ways, seeing that it is about them, that blows my mind.

De Shields: That’s why it’s so brilliant that this is the first commercial production of Death of a Salesman, in which the Loman family is Black. Once you take this piece of brilliant art that is beyond the exclusive domain of white audiences and white actors and put it in the mouths of people of color, then it truly becomes universal. Everyone can come to the experience and say, “They’re talking to me, they’re talking about me, and they are showing me that, yes, it’s difficult, but it’s not impossible.”

Once you take this piece of brilliant art that is beyond the exclusive domain of white audiences and white actors and put it in the mouths of people of color, then it truly becomes universal.

André De Shields

Clarke: That’s the brilliant thing. People think that they know this show. They’ve done it in school and college, whatever, and one of the things that people will say is, “That wasn’t in it before, or you’ve changed that line.”

And it’s like, “No, this is the play as it was.”

But people now see it differently. It hits them differently. It rings at their heartstrings differently. Because they are embedded in it now. It’s not just something that they’re watching on stage and going, “Okay, that’s about a particular kind of person, which doesn’t relate to me.” Now that people can see themselves, it just rings deeper with them. It’s just more visceral. Now, it’s more tangible. You see it, you smell it, and taste it now. And that’s the difference.

Recognizing Queer Liberation in an American Classic

Death of a Salesman won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama when it first premiered. And though it’s a far cry from Michael R. Jackson’s queer Black musical opus A Strange Loop, which earned the accolade in 2020, multifaceted, omnipresent queerness can be discovered through the themes of how we choose to define masculinity and textual references.

Belcher III: I do think that there’s a kind of liberation about how I look at masculinity. The fact I’m playing a character who has a kind of panache in a way of celebrating life and the fact that I don’t think I’m corseted into looking at that through a narrow lens, how I approach him is quite wide. I like to play with how he uses language and how that lives in his body, and I like to think that, in some way, that’s informed by my queerness, even if I’m not playing a queer character.

De Shields: Look at Willy Loman, who is the tragic hero of the piece. He is so disturbed about not being what the ideal is, that he lives his life in delusions, and he ends up destroying what little of him is human. Because he wants to be someone he is not.

Biff says, “I don’t know what I’m supposed to want.” That’s very queer.

If there is one young child out there that goes, “That’s possible for me,” then I’m doing my job.

Sharon D Clarke

Clarke: The fact that younger people can come, see the show, see the three of us, and see that it is so possible. When they know who we are fully and they can go there on Broadway, and they’re being themselves.

So, if there is one young child out there that goes, “That’s possible for me,” then I’m doing my job. Something we say to each other each night, “Is shine bright so that someone else can shine.”

That’s one of the most important things to me, knowing that it is possible and that you can follow your path and be who you truly are to every degree. Shine and allow others to shine as well.

Queer Joy, Power, and Freedom — Onstage and Off

Experiencing Death of a Salesman begins before the house lights dim. The production commissioned visual artist, photographer and educator SHAN Wallace to create a soaring mural that reflects the struggles and joys of the Black American experience as exemplified by the Loman family. The collage appears in the lobby of the Hudson Theatre and, as the artist says, “highlights the life-sustaining roles of matriarchs, those selfless providers, nurturers, and companions like Linda Loman.”

For the LGBTQ+ community, families of choice are often as powerful — if not more — than our families of birth. The artists’ creative processes are informed by these indelible relationships

Belcher III: There’s so much about what we do on stage. And in our journeys as artists, that’s about revelation and revealing of self. I really believe you can’t fully do that if you’re hiding. And we were talking to students a couple of days ago, and we’re talking about how embracing the weird, quirky things about yourself is like a superpower. So for me, my queerness is also like that. It’s my superpower. It’s a thing that gives me a perspective on the world. That is a fuel to be harnessed, not hidden.

My queerness is … my superpower. It’s a thing that gives me a perspective on the world. That is fuel to be harnessed, not hidden.

McKinley Belcher III

Clarke: I had to fight hard to be who I am, to stand up in myself as a woman who loves a woman. I am who I am, and I will be who I am regardless of what you say and regardless of what you think. If I don’t, then I’m not listening to myself, I’m not being me, and I’m not living my full potential.

If you’re hiding and trying to withhold, how can you fully be yourself? Step into your shoes and own that.

De Shields: Sharon’s not pretending. McKinley’s not pretending. I’m not pretending. Wendell “The Lion” Pierce is not pretending. He comes roaring on stage for three hours, and that just hits you.

Here’s my moment of insight: It is understandable that people are deeply moved by the play and understand that something tragic is happening to this everyday man. But the last spoken words in the play by Linda Loman is, “We’re free.” Now to Ben, who is Willy’s Angel of Death, that’s a mustard grain seed of joy, something as small as a grain of sand. That’s all Willy was trying to bring to his family, a bit of joy. He had to die in order to make it happen. It’s loaded, and that’s a lesson for the audience: Claim your joy now.♦

Death of a Salesman plays at the Hudson Theatre through January 15, 2023.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox