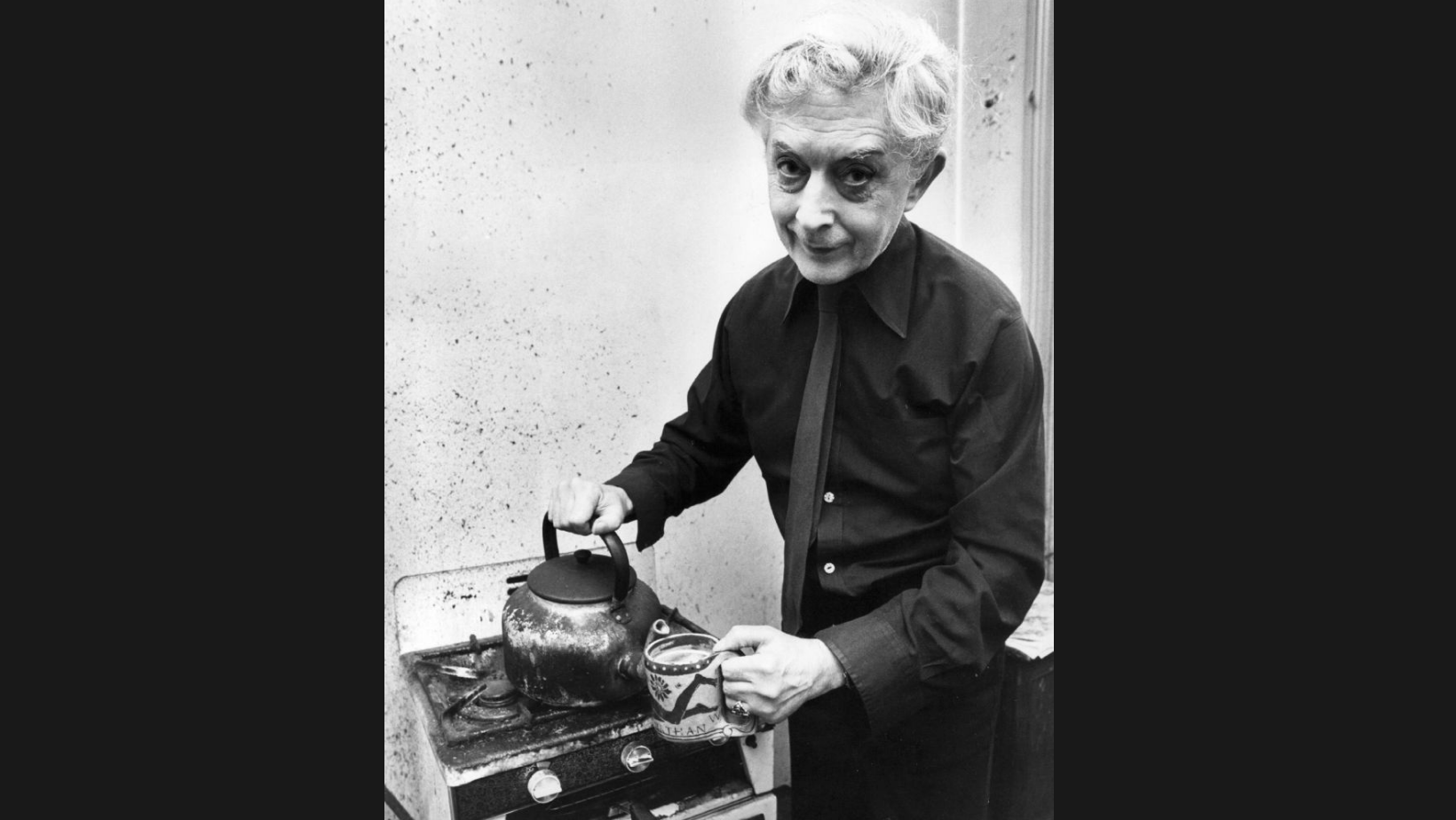

It’s easy to take for granted the tolerance and, indeed, celebration that the queer identity enjoys in an age where “Drag Race” has captivated audiences worldwide, from tiny tots to regrettably heterosexual daddies (not the fun kind.) However, the road to today has been messy. Quentin Crisp, an LGBTQ+ icon who was wearing makeup in public beginning in the 1930s, but with a markedly different reaction, explains: “There is no need to do any housework at all. After the first four years the dirt doesn’t get any worse.”

Crisp, who realized months prior to passing away at 90 in 1999 that she was not homosexual, but actually transgender, gained worldwide celebrity after the publication of her 1968 autobiography “The Naked Civil Servant.” Unlike the queens who grace the stage of “Drag Race,” Crisp’s influencer status didn’t happen overnight. The book which details her life in London as an openly queer person during the first half of the 20th century sold only 3,500 copies with its first printing- admittedly, a success for someone who deemed their life as essentially a failure. Fame, fortune, and everything that goes with it didn’t arrive for Crisp until her life was adapted to a made-for-TV movie starring Hollywood legend John Hurt (Ollivander in the Harry Potter franchise, the titular character in the David Lynch classic The Elephant Man, 1980) in 1975.

In retrospect, the BAFTA-winning film might be considered one of the first accurate portrayals of a transgender person in cinematic history, precisely because the filmmakers didn’t know they were making a film about a transgender person. If they had, it might have gone the way of other ill-fated attempts, such as the 1953 exploitation film Glen or Glenda, starring and directed by cult icon Ed Wood, himself a cis-identified crossdresser. Perhaps the first movie to seriously treat the topic of transgender identity, it nevertheless is widely held to be one of the worst films of all time, which actually ended up being a part of its appeal (the “so bad it’s good” effect.) Other attempts at capturing trans identity on celluloid similarly fell short, either because it banked on sensationalism (the Raquel Welch-starring adaptation of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckenridge, 1970) or because it relied on the tired old trope of villainizing that which is beyond the public’s comprehension (Hitchcock’s Psycho, 1960.)

Unlike the queens who grace the stage of “Drag Race,” Crisp’s influencer status didn’t happen overnight.

Modern audiences, enlightened by the likes of “Pose,” will recognize that something seems a bit off about the classification of Quentin Crisp as a gay man in the book and the film. Just because a man is gay doesn’t necessarily mean that he feels compelled to wear lipstick and rouge in broad daylight, or buy shoes two sizes too small so that his feet appear dainty. During Pride month, sure, a little drag is loads of fun, but Quentin herself admitted that she never attended the drag balls that popped up periodically in London’s gay underground during the ’30s and ’40s where, she reports, three-quarters of the revelers donned “feathered headdresses and diamanté trains”.

In fact, she admits to wearing full drag only once—a black silk number with a velvet cape—while on a date at a hotel bar with a fella who was, in turn, wearing a dinner jacket. “The evening,” by her estimation, “was a triumph, in that it was boring; nothing happened. Since then I have never worn drag. Its only effect on me is to make me look less feminine. In women’s clothes even a faint Adam’s apple, even slightly bony insteps, are harshly conspicuous.”

The gender dysphoria is hard to overlook here: if she was able to pass for a woman the one and only time she was in drag, then how conspicuous could her masculinity have been? It’s clear that Ms. Crisp’s harshest critic was herself, as, indeed, is the case for most of humanity. But Quentin didn’t see herself as belonging to humanity, nor did she really count herself as a homosexual. At the time, it was the only label that seemed to fit, however forced, so she put it on as a bridesmaid puts on a garish taffeta gown to appease her bridezilla. Still, even she realized she didn’t quite fit in with her gay brothers.

If Crisp was able to pass for a woman the one and only time she was in drag, then how conspicuous could her masculinity have been?

Take, for example, the long-lost art of cruising. In the days before hookup apps, meeting up in public places for quickie sex sessions was something of a rite of passage for gay men. Quentin never took to it, though not for lack of opportunity. Prior to her celebrity, Quentin scraped together a living and staved off starvation doing odd jobs, chiefly because her appearance and eccentricities kept her from gainful employment. The longest-running of these gigs was posing for life drawing classes at art schools in and around London- hence, the title for her autobiography. On a rare vacation, Crisp ventured to the English seaside town of Portsmouth (something of a gay mecca back in the day) where she recalls being “surrounded by sailors” on her first night who were kind enough to show her the seafront. When it became obvious that she was all talk and no “action”, they left her with two of the oldest amongst them, who made for good conversation over seemingly endless cups of tea all night long.

Late in life, but before her epiphany of trans identity, Quentin would confess: “I think my being gay is not sexual. My problem was one of gender. I didn’t want to be feminine so that I could meet more men. I wanted to be feminine to fulfill my idea of myself. People regarded me as having done the things I’ve done in order to be different from other people. I didn’t want to be different; I wanted to be more like myself than nature had made me.”

To be more oneself than even nature intended: that, in a nutshell, constitutes Quentin’s soapbox. On David Letterman’s late-night show during the early ’80s, she urged viewers not to conform to society’s expectations, but, rather, to hold fast to their individual identity and allow society to catch up to them. It was in the midst of the sexual and cultural revolution of the 1960s that Quentin discovered that what she had been wearing for decades—the clothes and makeup that left her in a bloody heap on the streets of London on several occasions—was suddenly all the rage amongst the youth of the day. And, then again, in the 90’s when she was in her 90’s, long after homosexuality was taken off the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, society came up with terminology to describe what she had been feeling and preaching for nearly a century: sometimes the outside doesn’t match what’s on the inside.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox