The Harlem Renaissance gave us a brilliant flowering of Black talent in just about every area of the arts, from writing to photography to poetry to choreography

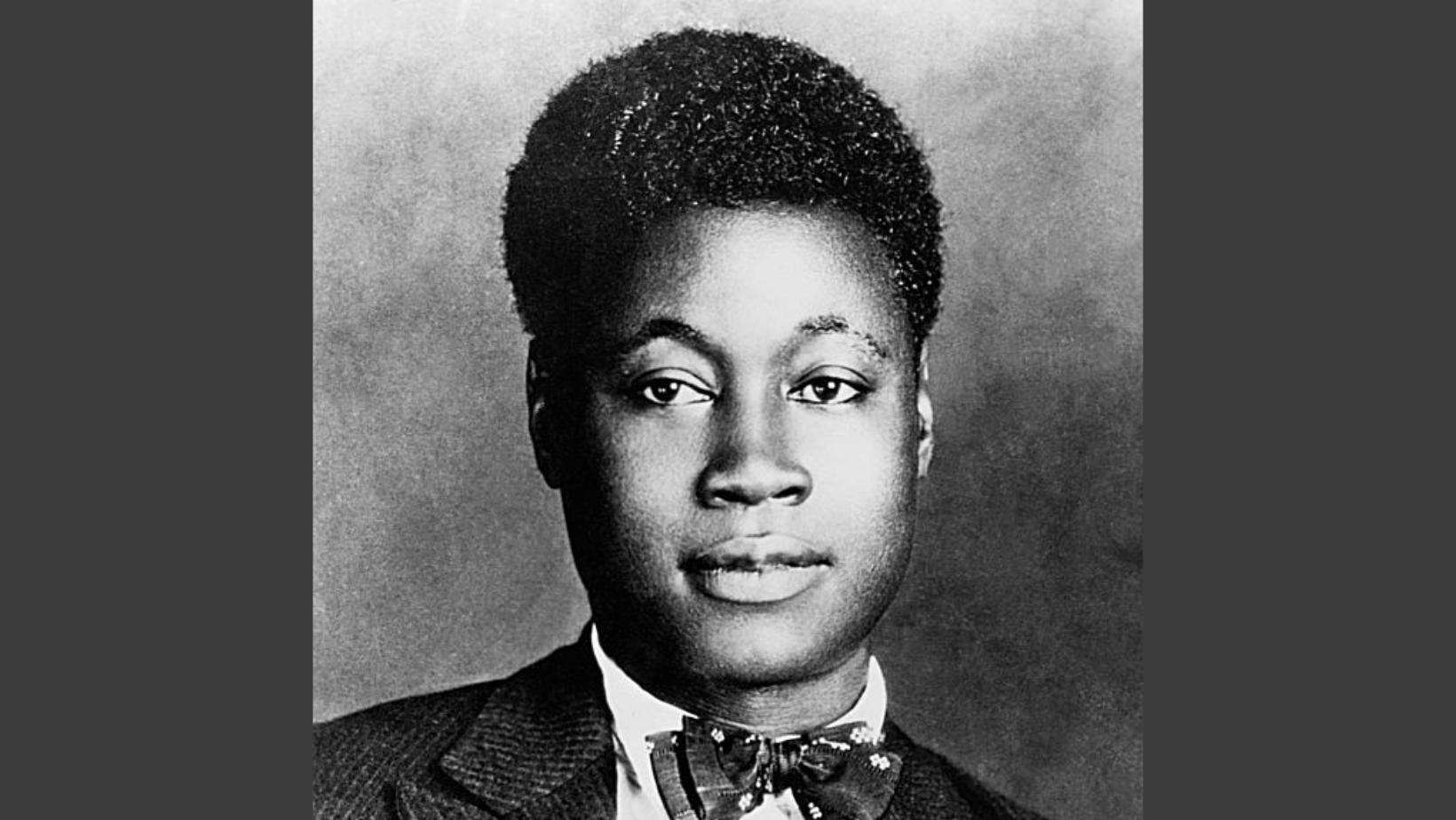

One such genius was the queer poet Claude McKay, whose work, though pitifully under-read and under-printed, is as essential today as it was then. Born in Jamaica in 1889, McKay made his way to the states as a young man, studying at the Tuskeegee Institute and Kansas State before emerging as a poet and novelist with his first book of poems, “Songs of Jamaica,” in 1912.

By 1914, McKay was in New York making a name for himself as a poet and writer. His work was championed by Charlie Chaplin, who read one of his chapbooks during a trip abroad in 1922, as well as by the writer Aimé Césaire and fellow poet Langston Hughes, with whom McKay struck up a correspondence in the 20s. His books, however, were another matter: after the publishing of McKay’s 1928 roman a clef “Home to Harlem,” W. E. B. Du Bois criticized the writer for pandering to the white publishing establishment’s desire for tales of “black licentiousness” such as the kind white writers like Carl Van Vechten had begun to peddle. But “Home to Harlem,” along with McKay’s follow-up novel “Banjo,” still struck a chord with Black readers, and in 1922’s poetry collection “Harlem Shadows,” the bohemian Harlemites saw themselves reflected in the “dangerously utopian” ideas the poet set forth about society and socialism.

After the violent “Red Summer” of 1919, McKay traveled to London and then Russia in search of a less racist political climate. He would stay away from America for 11 years, returning to in the late 1930s, where he would work on a new memoir, which would be posthumously published as “My Green Hills of Jamaica” in the 1970s, long after McKay’s death in 1948.

McKay was open about his bisexuality throughout his life, pursuing relationships with men and women and writing queerness into many of his more sensual poems, and using gender-neutral pronouns to speak of an unknown lover. But his best-known work by far is his 1919 poem, “If We Must Die.”

In 2020, the poet Kevin Young spoke on the legacy of “If We Must Die,” written in the aftermath of New York’s Red Summer, in which Black Americans were targeted in racist attacks across the country, from Harlem and Syracuse, New York to Arkansas, Chicago, and Washington D.C. over the course of a few months.

Focusing on the line, “though far outnumbered, let us show us brave,” Young ties McKay’s words to the modern fight for equality and racial justice. “It’s naming this thing, and by that way, getting past it.”

The struggles McKay wrote about are still clearly alive and well today, and though many of his works remain out of print, McKay’s legacy is destined to survive. He wrote about pain, strife, racism, queer love, Blackness, and beauty, and he saw the future. He saw the present clearly, too, as evidenced by his 1920 poem “The Lynching,” 10 years before the poem “Strange Fruit” was written, and 18 years before that poem became one of Billie Holiday’s signature songs. In it, McKay describes a common Southern scene with unflinching clarity, describing the children present at the hanging as “little lads/lynchers that were to be/danced around the dreadful thing in fiendish glee.”

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox