On the corner of Knipstraat and Daalsesingel in Utrecht, the Netherlands’ fourth largest city, a cluster of pedestrians waits to cross the street. When the time comes, the traffic light on the other side of the Knipstraat will turn green, indicating that it’s safe to cross.

Pedestrian traffic lights in the Netherlands take the form of a red male figure viewed head-on for “stop,” and a green male figure shown in profile with one leg raised for “go.” But in early March of 2016, three of Utrecht’s pedestrian lights underwent a radical makeover.

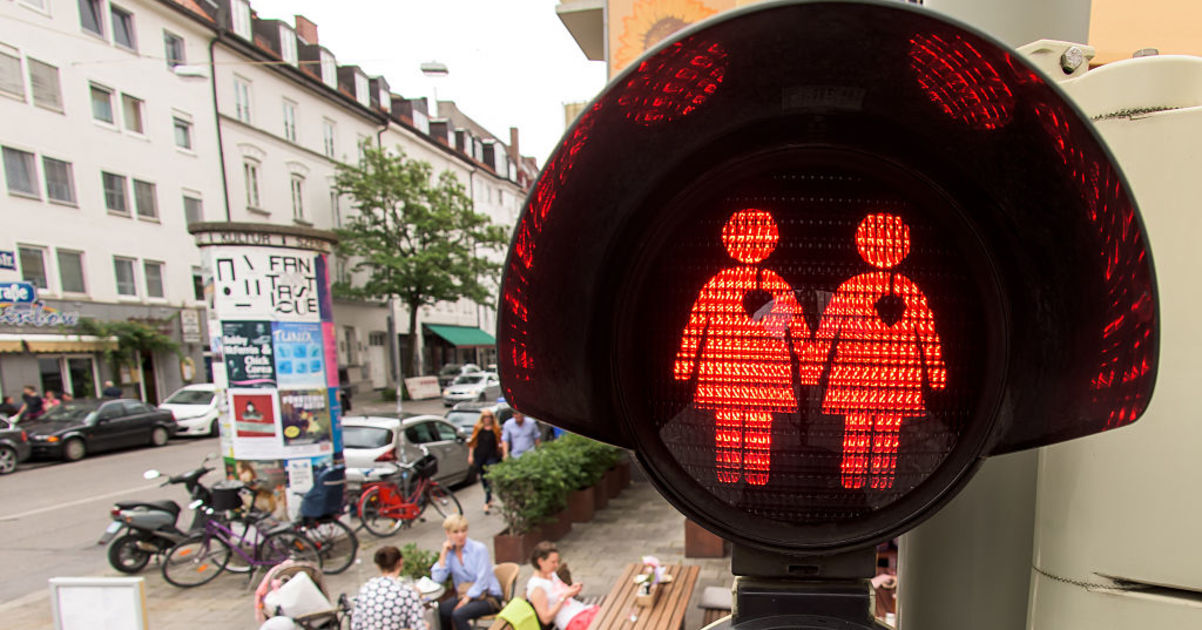

At the intersection of Knipstraat and Daalsesingel, the lone male figure was replaced by two females, holding hands and surrounded by hearts. In the opposite direction are two additional regenboogverkeerslichten, or rainbow traffic lights. One depicts a gay couple, the other, a heterosexual one.

City alderman Kees Geldorf, who was on hand for the March 8th unveiling, told Dutch news broadcaster Nos that the lights are a reflection of Utrecht’s diversity. “Each time you come upon one of these lights is an opportunity to reflect on that,” he said.

Utrecht is the most recent of a growing number of European cities to install the rainbow traffic lights. In May of 2015, the first lights appeared in Vienna, Austria in preparation for the Life Ball AIDS charity fundraiser and the city’s stint as Eurovision Song Contest host.

Originally intended to be temporary, the Ampelpärchen, or traffic light couples, were made permanent due to public pressure. A Facebook page calling for the preservation of the lights accumulated more than 4,000 Likes in a matter of hours. The lights even received international attention, scoring mentions in The Washington Post, The Guardian, The BBC, and TIME among others.

Soon after, the Austrian cities of Linz and Salzburg adopted the design, followed by Cologne, Munich, and Hamburg in Germany. Last fall, Helmond and Arnhem in the Netherlands followed suit. Lucerne, Switzerland is debating jumping on the bandwagon as well.

“Being inclusive of LGBTQ+ people in public-works is something that helps eliminate stigma and hate by making sure that they are visible, making sure that diversity is represented,” said Victoria Rodriguez-Roldan, Trans/Gender Non-Conforming Justice Project Director at the National LGBTQ Task Force, headquartered in Washington, DC.

That’s why the all-inclusive nature of the traffic lights is so important, according to Pepijn Zwanenberg, the Utrecht City Councilmember behind the implementation of the traffic lights. The goal is “to show diversity, not single one group out from the rest,” Zwanenberg said.

“If you’re from [somewhere less tolerant] and you hear about this or you see this and you’re gay or lesbian or transgender, I think it can be very powerful,” Zwanenberg added. The lights send a message of welcome and the validity of love of all kinds, while at the same time helping normalize LGBTQ+ people.

Reactions to the lights have been mostly positive, according to Zwanenberg and Dutch gay rights group COC Midden Nederland. But not everyone is on board. Comments on Twitter, Facebook, and the Dutch news organizations reporting on the development are overwhelmingly negative.

The most common accusation is that the lights are guilty of the very thing they are purported to be fighting – discrimination – by singling out the gay community and excluding heterosexuals. Since the media frequently bills the lights as “gay traffic lights,” most critics are unaware that a heterosexual couple is included.

Most infuriating to detractors is the cost of the project, which set the city of Utrecht back €1,200 (roughly $1,350 USD). A waste of money, one commenter argued, for what amounts to little more than a “photo op for tourists.”

The well-intentioned traffic lights were met with similar criticism in Austria. In Linz, city traffic official Markus Hein had the lights taken down just five months after their debut. “Traffic lights are for traffic and should not be misused to impart advice on how to live your life,” Hein, a member of the right-wing Freedom Partytold the Kurier. The city council voted in January 2016 to restore the lights.

In Vienna, The Freedom Party filed a criminal complaint against deputy mayor and traffic official Maria Vassilakou, who initiated the placement of the lights at 120 pedestrian crossings throughout the city. The Freedom Party claimed that the lights were a waste of taxpayers’ money and a violation of traffic codes.

The complaint ultimately proved unfounded and was subsequently dropped. City spokesman Andreas Baur told INTO that, in addition to complying with Austria’s road traffic requirements, “the diversity-themed symbols on the traffic lights [are] part of a road safety campaign” the city is pursuing to reduce the number of fatal traffic accidents.

Pedestrian safety is a major concern in the Austrian capital, where, in 2012, 16 pedestrians were killed and more than 1,000 were injured, according to Statistics Austria. Twenty-two of those injured at pedestrian crossings in 2014 were children. To draw attention to the often-ignored traffic lights and motivate pedestrians to adhere to their signals, the city of Vienna replaced the traditional symbol with the unique, more visible Ampelpärchen.

Vienna is not the only city to experiment with this concept. In Augsburg, Germany, city officials moved to embed traffic signals in sidewalks, where Smartphone users would be more likely to see them. Smart, the company best known for its self-titled mini car, designed a dancing traffic signal for a crosswalk in Lisbon, Portugal. Passersby slip into a booth in a nearby square to bust a move, which is then mimicked in real time by the red figure in the traffic light. Smart reported that 81% more people stopped for the red light when it was dancing.

Many European cities have their own unique traffic light designs, of which city dwellers are fiercely proud. Berlin, Germany, for example, has its Ampelmännchen; behatted cartoon men implemented in East Germany in 1969 and saved from extinction by the public after the reunification of Germany in 1989. It’s entirely possible that the rainbow traffic lights will become part of the local identity of the cities that adopted them.

When asked if a similar initiative might be possible in the United States, a Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) spokesperson explained that, although the FHWA does have a set of nationwide standards to avoid confusion for road users, it’s ultimately up to local officials to decide which images to display on their traffic signs and signals.

West Hollywood, CA Councilmember John Duran, who sponsored the city’s rainbow crosswalks, expressed an interest in exploring the idea in WeHo. Seattle traffic engineer Dongho Chang said the City of Seattle would also be “open” to experimenting with modified pedestrian traffic lights. Once approved, they could be tested “at locations that have ‘all-way’ walks, where all vehicular traffic is stopped before pedestrians are provided the signal to cross,” he said.

Obviously, cost would be a major deciding factor, as well as location and public receptiveness. “It might look trivial and it might sound trivial – most people don’t spend their days thinking about crosswalk lights,” said Rodriguez-Roldan. “The point is, even that is a way to show inclusion.”

Though traffic lights alone won’t guarantee acceptance and equality for the LGBTQ+ community, they just might be a step in the right direction.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox