Many faces and many stories are among them. Take, for instance, Dee Whigham, who had recently begun her medical career as a nurse at a medical center in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

A definition of the word “diva,” was kept on her Facebook page: “A lady who does NOT allow any other passengers on her plane.” Rae’Lynne Thomas from Columbus, Ohio was a performer and “fashionista” and wanted to look her best at all times, “dressed to the nines to clean the kitchen.” On India Monroe’s Facebook page, titled “India thedarkvixen,” she declared about herself that “it is just the beginning, don’t count me out yet, I am a work in progress.” She lived in Newport News, Virginia.

All of them are transgender women from around the country, 27 in all, and all of them brutally murdered throughout 2016. It wasn’t the end, wouldn’t be the end for any of them, however.

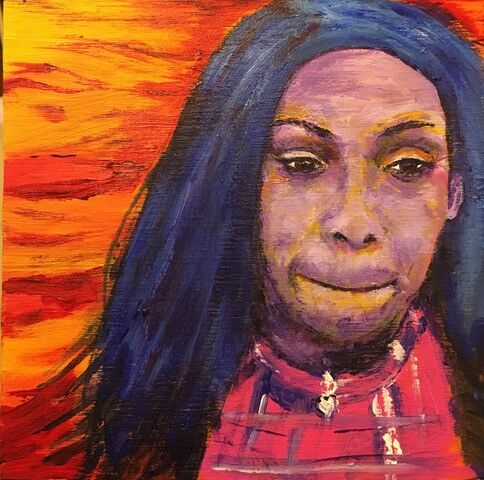

Instead, all of these hopeful, bright, shining human beings now hang along the walls at Chicago’s Center on Halsted, rendered in dozens of lovingly painted portraits. “This list is from recorded homicides,” says Wachowski, “though I’ve taken the liberty of some additions due to suspicious circumstances. It is partial and by no means considered complete.”

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

The Wachowskis have long made work that famously functions at the intersections of philosophy, artistic representation, ideology and self, sex and gender identity, with technology and a healthy dose of reflections on the necessities of jouissance thrown in.

At times, art-making as a social and cultural discourse can reflect positive shifting political realities. Many ardent fans of their Netflix series Sense8, for instance, saw themselves in the multivalence of character consciousnesses and understood it as an explicit attempt to represent users of newly emergent plural, gender-neutral personal pronouns in our culture.

But while they were celebrating alterity and difference onscreen, there was simultaneously a creeping, undeniably persistent, grim march forward of violence against transgender people taking place across the country. Ferocious and bloody, the violence has seemingly taken place unchecked.

Unlike other frontiers of the civil rights movement, such as with the enshrinement of gay marriage and other rights into law, there remains a lack of proper juridical and legislative protections to sufficiently safeguard the rights of transgender people and a widespread, pervasive establishment of bigoted cultural norms that push back against that from happening. In fact, these lack of protections emboldens violence against them.

After coming out as transgender herself in March 2016, Lilly Wachowski took a break from working on the popular series, so wrenched by the violence that she began to explore her reactions to it in paint, producing a series of portraits shown collectively in June 2017 at Chicago’s Center on Halsted in an exhibit titled Say Our Names.

“This series of portraits began toward the end of July 2016,” says Wachowski, “an outlet for the overwhelming emotion I was feeling in the relentless waves of mortal acts of violence against trans people over the course of the year. With each headline, each murder, I felt wanting to connect, to remember, to honor.“ It was in the Center that she found a safe haven for sharing her series of portraits, works that painstakingly memorialize those whom so many continue to regard as less than human.

It’s inarguable that sex and gender fanaticism has enjoyed a generalized resurgence in 2017 America, with evidence of its hateful revanchism everywhere. It’s also unsurprising, in a nation founded on a roll-call of atrocities, whether slavery, the Indian genocides that preceded the Westward Expansion or the refusal to accept the citizenship of those Chinese who helped build the railroads afterward, that America today continues to persist in its long history of supremacist leanings. Those leanings are influential and wide-reaching.

Indeed, it’s clear that Nazi lawmakers planning the drafts of their own Blood Laws determined that American juridical stances on racial purity in anti-miscegenation laws were too severe, even for them (we claimed a “single drop” of racially-tainted blood was enough to invalidate superior identity; for them, you needed to have a few grandparents worth of tainted blood in the lineage).

So, whether it’s Anglo-Saxons over black, brown and yellow people; or straight, cis-gendered sexual relationships over LGBTQ people, there’s been no shortage of demonstrable nationalist argument for these hierarchies of nature in which some people are deemed superior to a wide range of inferior others. It’s truly sickening.

And, whether in President Trump’s specious arguments about transgender service in the military, or the overturning of the “bathroom bills,” and on and on, transgender people are today more and more often at the center of that nationalist backlash.

In fact, Trump’s willingness to stoke the fires of that supremacist fanaticism was a major motivation for the portrait series, and an inspiration for the defiant footing that necessitated it.

“I write this the day after a Trump presidency was confirmed,” Wachowski notes, seething with indictment of the President’s divisive rhetoric. “We LGBTQ collective must fight for and protect our own against the tide of ignorance and hate. Fight for and protect first, then educate.”

In the very same month when Lilly Wachowski announced her transgender identity, 16-year old dancer Kedarie/Kandicee Johnson (who identified both as transgender and genderfluid, and who went by both names), was found shot to death in an alley with multiple entry wounds. They had only just moved to Burlington, Iowa, where they were killed, in an attempt to escape the gun violence in their hometown Chicago. Among the 27 portraits painted by Wachowski, Johnson’s was among the first deaths to occur after the filmmaker had become a publicly-recognized transgender figure.

That her portrait, like that of the others, is rendered in the art-historical vocabulary of naive figuration lends to its earnest, heartfelt quality in a way that syncs with the abject and assigned “inferior” status by populist narratives of its subjects. This embrace and alignment of the perspective with the abjection of form, technique, and subject is itself an act of defiance. Colors are at times blocky, chiseled, then explode against one another, flaring up in raw purples, oranges, reds; what matters most is the person revealed in their movement through time.

“I utilized a color palette with the hope the portraits could offer a vibration of the subject’s life and humanity so that the viewer would also be able to connect, to remember, and to honor.”

Wachowski’s portraits evince a desire to reconnect them with the world beyond the populist social and cultural elements that rejected them, past the hatred and bigotry, to reconnect them with the world they’ve left behind. It’s a choice reflected even in the surface of the materials Wachowski chose to work with: “Acrylic on wood panels. The organic fibers of the wood felt apropos of the organic nature of these lives and our interconnectedness.”

And that interconnectedness is crucial not only for understanding the project but for understanding the importance of equality in society: without it, those supremacist delusions can grow and spread like a malignant virus, tearing society apart from within the belief systems of its members.

Ultimately, each individual attempt to restore each of these 27 slain women to our cultural memory through portraiture is an act of subversion against those in the culture whom would see them erased, wiped out and forgotten.

“We must recognize these murders for what they are; a genocidal project,” Wachowski explains. “Trans people are under attack and trans women of color specifically are being singularly and systematically wiped out.” There’s only one antidote, she writes, summing up the need to build a more salutary, inclusive culture in one short, poetic refrain:

We, the dead and

We, the living

Will not be erased; Say Our Names!

Say

Our

Fucking

Names.