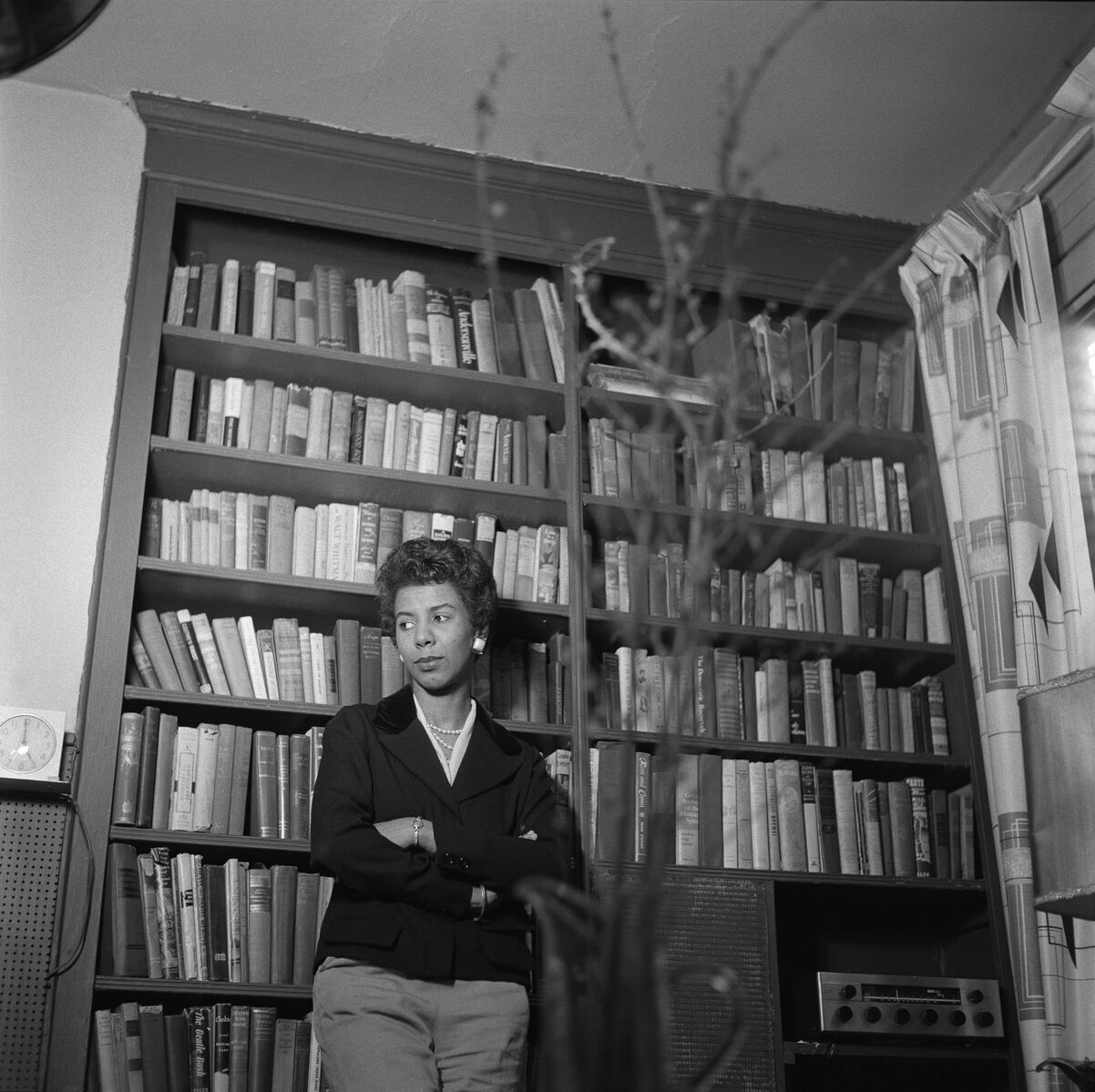

The first play Lorraine Hansberry wrote at only 29 years old became such a massive success that most teens now read it in their high schools. A Raisin in the Sun was not just a hit Broadway show, but an integral moment in Black visibility in theater and the fusing of personal politics and pop culture. A radical, progressive Black woman from Chicago’s South side, Hansberry became what many at the time considered an unlikely hero, defeating every stereotype stacked against her, and using her public platform to out about racial inequality, classism, gentrification, and sexism.

Yet while most of her battles were out in the open, there was one she kept more private, and that was her identity as a lesbian.

In 1957, two years before A Raisin in the Sun would hit the Great White Way, Hansberry began writing letters to The Ladder, the first national lesbian’s magazine widely distributed in secret.

“I’m glad as heck that you exist,” she wrote the publication. “You are obviously serious people and I feel that women, without wishing to foster any strict separatist notions, homo or hetero, indeed have a need for their own publications and organizations. Our problems, our experiences as women are profoundly unique as compared to the other half of the human race. Women, like other oppressed groups of one kind or another, have particularly had to pay a price for the intellectual impoverishment that the second class status imposed on us for centuries created and sustained.”

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

“Thus,” she continued, “I feel that The Ladder is a fine, elementary step in a rewarding direction.”

Most depictions of Hansberry’s life tend to ignore her self-professed lesbian identity, as she was for a short time married to writer/publisher Robert Nemiroff. But in the new documentary Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, premiering on PBS tomorrow as part of their American Masters: Inspiring Women programming, filmmaker Tracy Heather Strain touches on Hansberry’s hidden relationships with women, and and her inability to embrace homosexuality as another platform to publicly hold.

Hansberry biographer Margaret Wilkerson (whose book is forthcoming) worked with Strain to uncover some of Hansberry’s history, and what they found in her diaries and letters to and from friends is she was very challenged by her sexuality.

“It was a part of her life that she seemed to compartmentalize,” Strain told reporters at the Television Critics Association Press Tour. “The other people in her life were not aware, for the most part. Burt D’Lugoff, who was a friend of hers for a long time was aware, and few other people. But as one of the people say in the documentary, she wasn’t very public about most of her life, but this part of her life, being a lesbian, was kept private.”

The women she had relationships with were not named in Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, but the late Edith Windsor appears to share memories of Hansberry, saying a friend of hers was involved with the playwright and activist.

“We went to the same parties, we read a lot of poetry together,” Windsor says. “I found Lorraine just delightful. I thought she was smarter than hell and I thought she was so lovable.”

Famed lesbian pulp novelist Ann Bannon also appears in the doc to contextualize the time Hansberry lived in. The late ’50s and early ’60s were not welcoming to homosexuals, much less Black gay women.

“She was an artist, a black, a woman, and a gay person at a time when these groups were not connected,” says Wilkerson in the film. “She didn’t have a community where she could. She didn’t really have that. Most of her gay friends were white women.”

“I think it was a real struggle for her,” Strain said at TCA, “and I think that contributed to [her] lonliness.”

Not only did she write letters to The Ladder, but Hansberry contributed a short story to the magazine under the pseudonym Emily Jones. (In addition, she published three stories in the major gay publication at the time, ONE, using the same anonymous pen name.) These works and her correspondence with The Ladder were turned into an exhibit, Twice Militant: Lorraine Hansberry’s Letters to The Ladder, which ran from 2013 through 2014 at the Brooklyn Museum.

“I wanted to leap into the questions raised on heterosexually married lesbians,” Hansberry wrote to The Ladder. “I am one of those. How could we ever begin to guess the numbers of women who are not prepared to risk a life alien to what they have been taught all their lives to believe was their natural destiny?”

Still, Hansberry is often straightwashed by those praising her work, which not only included A Raisin in the Sun but several other plays, including The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which included a gay character. But post-Raisin, which she adapted for cinema in 1961, Hansberry was largely celebrated for her 1964 book The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality and subsequent speeches and writings on civil rights in America. She tragically died of pancreatic cancer at 34 in 1965.

Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart details the solitude Hansberry wrestled with toward the end of her life, as evinced through her personal diaries and correspondence with friends. Part of that solitude, Strain argues, was her undisclosed lesbianism, which was part of the reason she moved to Croton-on-Hudson, a small town about 30 minutes outside of New York.

“I think it was a real struggle for her,” Strain says, “and I think that contributed to [her] lonliness.”

She wasn’t always alone, though. After returning home from the hospital in 1964, she wrote about a lover who had slept over and helped take care of her.

“So much was pent up. I consumed her whole,” she wrote. “I recalled also when she first lay in my bedhow very, very wet the place on my leg when she moved. She was very ready.”

Despite Hansberry’s queerness becoming more obvious posthumously, it is often left out of most scholarly discussions of her influence, partly, it seems, because her ex-husband was the one who took control of her work after she passed. In a 1969 essay, feminist lesbian writer Adrienne Rich asserts that the “problem” with Hansberry is that a heavy hand has been laid upon a large part of her writing made available after death. And part of it, sadly, was that she died too soon.

“How would she have responded to the poetry of June Jordan, to a Black feminist manifesto such as the Combahee River Collective statement, to Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens and Meridian, to Audre Lorde’s The Black Unicorn or Scratching the Surface, to the music of Bernice Reagon, Mary Watkins, Linda Tillery; to Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide…?” Rich writes. “What would she have made of Barbara Smith’s declaration that ‘I want most of all for Black women and Black lesbians somehow not to be so alone. This … will require the most expansive of revolutions as well as many new words to tell us how to make this revolution real.”

Hansberry may not have been alive to witness these works, but she undoubtedly had a role in making Black women more worthy of being seen, read, and respected. Being the first Black woman to have written a Broadway playa massive hit play, at thatafforded her the opportunity to be a mouthpiece for the otherwise unheard. Unlike her friend James Baldwin, however, she could not reconcile her queerness in the same way, and so her lesbianism is often left out of conversations about her life and work.

If there’s any solace viewers can take, however, it’s in Wilkerson’s assertion that perhaps Hansberry’s inner turmoil helped to inspire the legacy she left behind; the words that inspired so much conversation and action.

“Maybe that helped to create the brilliant work that we see,” she says, “because that’s what she was dealing with.”

Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/ Feeling Heart premieres this Friday, January 19 at 9:00 p.m. on PBS

Images by David Attie via Getty