When I meet Korean artist and activist Heezy Yang at the bar he manages atop Seoul’s famous ‘Homo Hill,’ he is hard at work setting up the sound-system, unloading crates of beer, and preparing bar equipment. This is to be expected from a creative who embraces multiple mediums; not only does Yang make politically-charged illustrations, he also writes, stages public performance pieces, and occasionally performs in drag, all in the name of creating visibility for queer communities across the country.

This fascination with art in all its various incarnations is one which he credits to his parents: “I always liked drawing, and I’ve always been interested in seeing art. I think it’s partially because my dad was a film critic, so he would take me to see movies and his artist friends’ houses and studios. My mom was a typical Korean mom,” he chuckles. “She sent me to different schools and academies to learn – some of it was useless, but some of it was pretty cool!”

It was in these extracurricular classes that Yang learned some of the basic skills required to create art, and later went on to experiment and develop a skill-set of his own. It wasn’t until he started to feel frustrated and eventually dropped out of college, where he was studying for a business major, that he started to think seriously about channeling his artistic passions into an actual career.

“I was thinking about where I should go with art, what I should make,” he recalls. “Obviously I make and draw whatever I feel like, and that’s what a lot of artists do because it’s fun to do, but I guess because I had quit school I thought I should be more serious about it.”

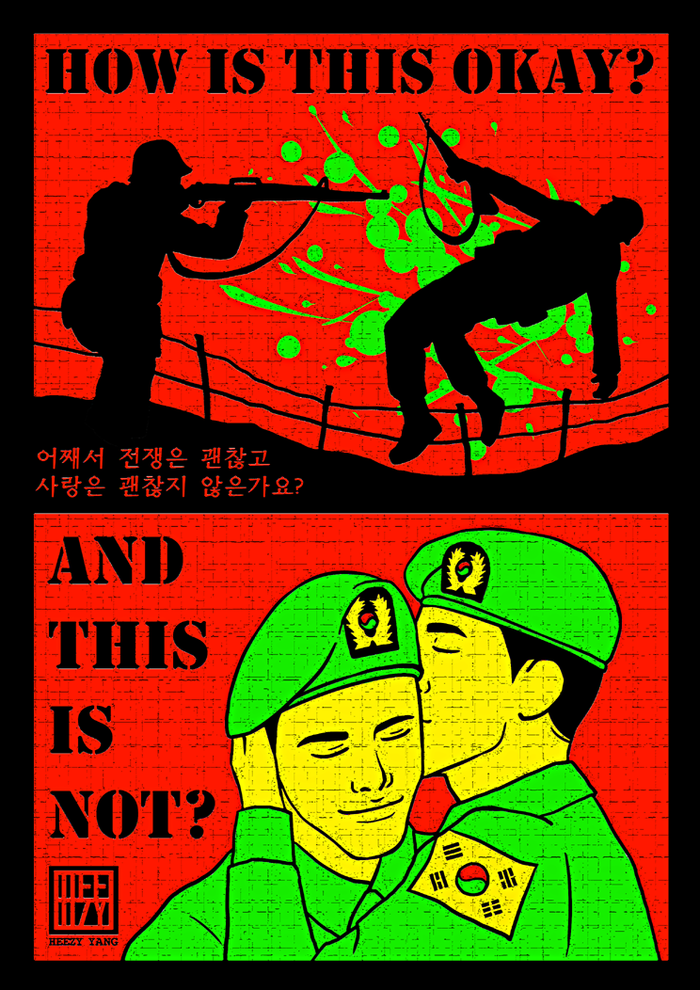

Coincidentally, this was also around the same time that Yang was “gradually coming out” to his friends and family; the two threads quickly became intertwined, imbuing his work with a sense of his own queer identity by default. “I had heard and seen a lot of things happening around me regarding LGBTQ issues in Korea, and obviously what you see and what you hear affects you,” he says, unintentionally echoing a sentiment which will doubtless resonate with marginalized people worldwide. “I was starting to get involved in things like Pride here in Seoul, which is also called the Queer Culture Festival, and making friends with more LGBTQ and human rights activists. I wanted to somehow get involved in that fight; I wanted it to be my fight, too.”

Yang describes even the most progressive pockets of Korea as still being relatively conservative, but also highlights that people are mostly physically safe: “People here aren’t very violent, so it’s quite safe not only for queer people but for people in general.” This doesn’t mean that discrimination in the workplace, bullying, and a lack of access to jobs and education aren’t still commonplace – despite being physically safe, LGBTQ people are still heavily marginalized within society. I mention the North/South divide which Western media is quick to focus on, but he glosses over the question, arguing that there are still attitudes in South Korea in dire need of attention.

“We still have a long way to go, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s going to take a long time,” he enthuses, pointing out that the audience for Seoul’s annual Queer Culture Festival has expanded from 2000 to 85,000 in the space of just a few years. “The awareness level and the visibility is increasing really quickly, I think. Maybe the politics and the systems that will actually protect our rights aren’t shifting yet, but the exposure is also really important and marks the first few steps.”

Although Seoul is undeniably progressive in comparison to the rest of South Korea, Yang optimistically points out that Daegu – “the most conservative city” – has had its own Pride parade for a number of years, highlighting that attitudes of intolerance are increasingly being met with resistance. Elsewhere, Busan had its first event this year, and Jeju Island will stage its first ever Pride on October 28, with Yang performing as part of the celebration.

LGBTQ nightlife is another core focus of Yang’s – especially in countries which don’t openly accept queerness, these havens of acceptance are sorely needed. “I mean, first of all, I think it’s really fun,” he smiles when I ask about the importance of Seoul’s LGBTQ club scene. “Because you’re oppressed within society, it is harder to be publicly affectionate. Nightclubs and bars, for some people, are the only places that they can be openly gay, meet people, and actually express themselves. For that reason, I guess it’s maybe more important here in Korea than it is in other less conservative countries.”

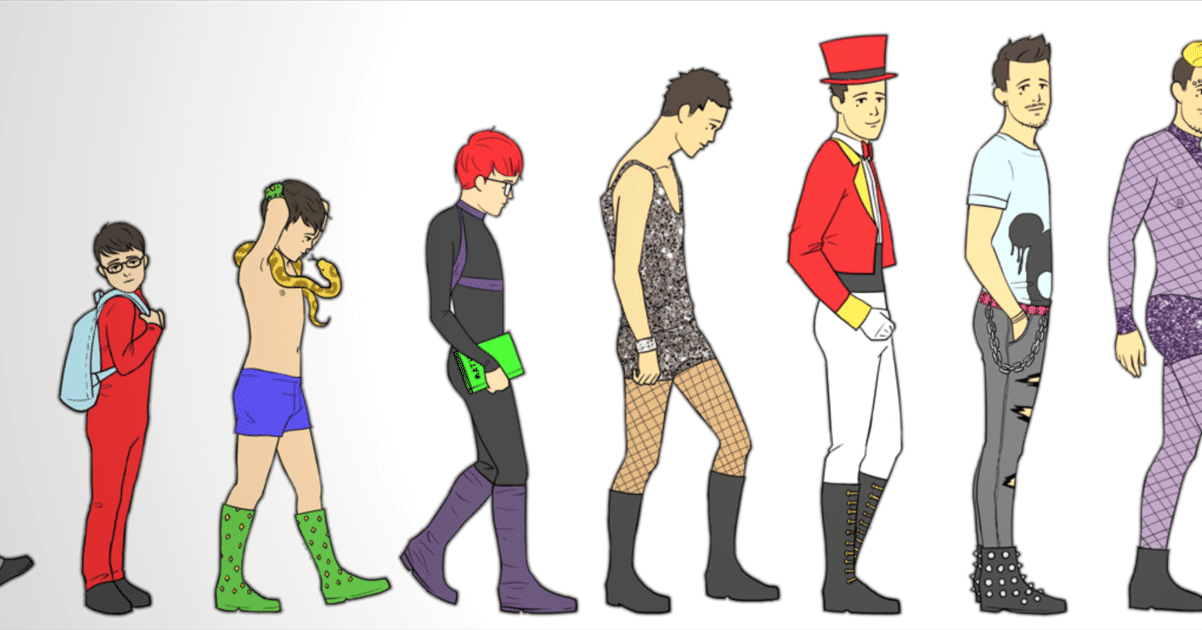

Later that night, I get the chance to experience the fun Yang describes first-hand – Seoul is teeming with bars and clubs that should be high on the priority list of any LGBTQ traveler. Newly-opened QBar stages regular drag nights (they also have cheap drinks and a playlist brimming with pop hits), whereas the handful of queer and queer-friendly bars and clubs in Itaewon offer something for everyone. Yang himself performs at these events sometimes, although he’s quick to point out that he doesn’t necessarily see himself as a drag queen: “It’s just another medium for me,” he explains, before name-checking local talents like Vita Mikju, Kuciia Diamant and Charlotte Goodenough as his own personal favorites.

By putting themselves out there, these various creatives are actively seeking to build queer communities – and, if Yang’s words are any indication, their efforts are paying off. I ask if he ever gets nervous about his public performances, but he says the reactions are largely positive – “people will just take pictures and be like, ‘Hey, you’re really cool!’” Even the negative reactions are rarely extreme – there are no counter-protests or examples of hardcore verbal abuse, just disapproving comments and the occasional stare.

As for his own plans, Yang wants to keep learning and create artwork around other issues, like the environment and the body-shaming, which is still prevalent in queer communities in particular. He is also candid about his struggles with his mental health: “I want to do two things, the first of which is make art about my own experiences, the depression that I go through, me as a person. That’s one thing. The other is to express my political views – I want to create art about injustice to fight what is wrong.”

The bar begins to fill up, and the conversation starts to wind down. To finish, I ask how he feels to have developed a public profile of sorts; after all, creating work and putting your name to it can be mentally and creatively draining, especially when your artistic output is intrinsically linked to your own personal identity. “It depends. There are times I would rather stay home alone, work on projects and just generally be a bit depressed, but there are definitely times I want to go out there and do something, whatever that might be, so when I’m in the right mood and have the right motivation, I don’t really get nervous. I’m an introvert but, at the same time, I am an occasional exhibitionist,” he concludes, with a chuckle. With that, he’s back behind the bar laughing, joking, and working hard to strengthen the queer scene in a country which, despite considerable progress, still desperately needs it.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox