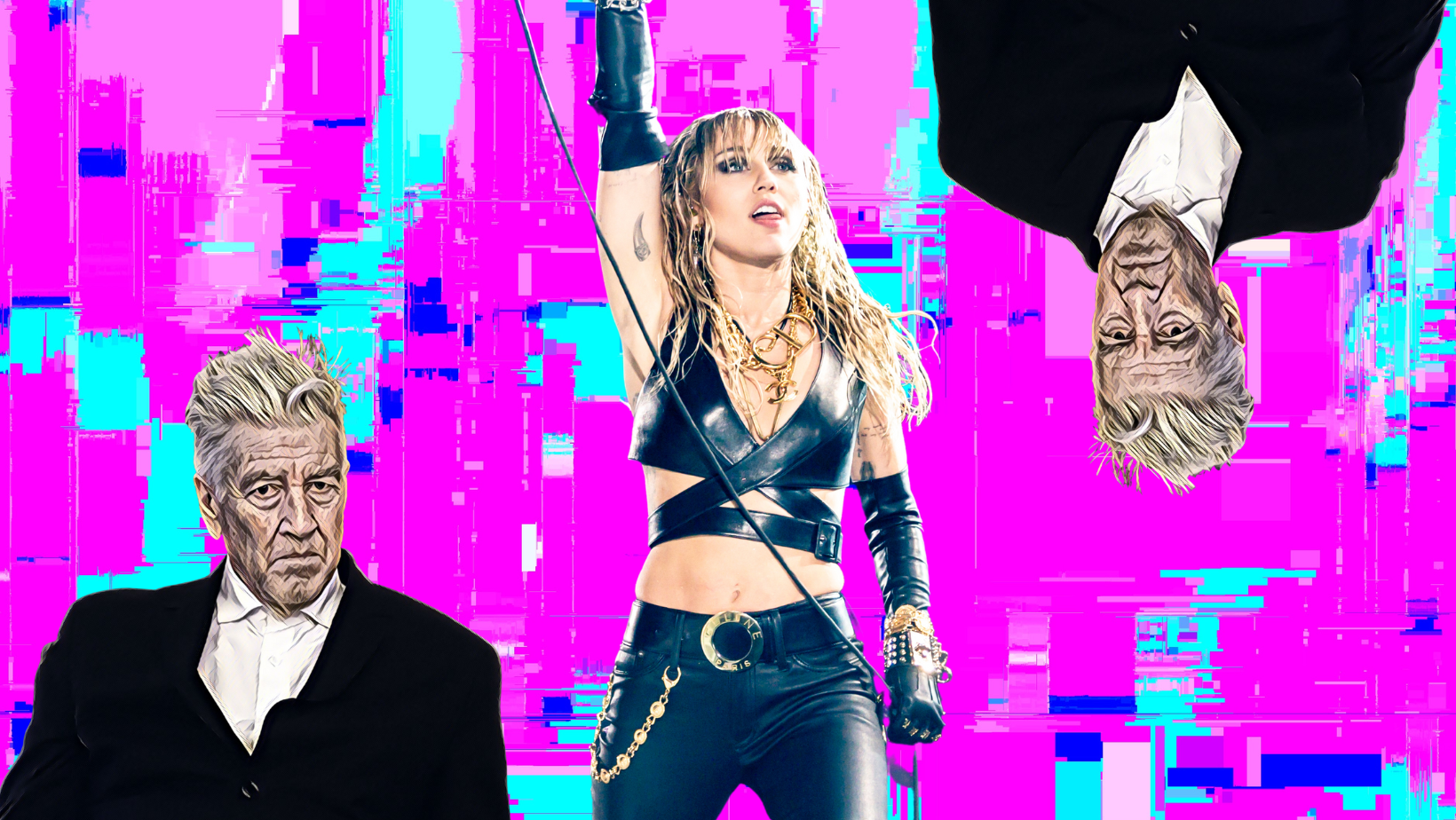

“If it weren’t for David Lynch, there would be no Hannah Montana.”

When Billy Ray Cyrus first said these fateful words in a 2011 GQ interview, he meant that his appearance in Mulholland Drive (2001) led to more acting gigs, thus giving his daughter—Destiny Hope Cyrus—a foot in the studio door.

But there’s more connecting David Lynch and Hannah Montana than her dad’s star turn as Gene Clean.

“Lynchian” has come to stand in for ‘surreal,’ but if we get more specific, it becomes a beneficial way to understand American cultural phenomena and events. Taking Mulholland Drive as a guiding compendium of his ideas, we can see David Lynch’s surrealism uses the uncanny to double-expose our post-War nostalgia and the American Dream. He achieves this by having his uncanny slip in such a way as to reveal the mechanisms of performance and the manipulation of belief.

As a prelude to the end of her Hannah Montana character, in which Miley begins to take off the blonde wig and start out on her own, Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus: The Best of Both Worlds Concert (2008) is a true Lynchian Spectacle. It may even out-twist the famously esoterically-minded director.

In Hannah Montana, the title character famously tries to have “the best of both worlds.” The series follows everygirl Miley Stewart (modeled after Cyrus herself) who’s living a double life as superstar singer Hannah Montana, while trying to have a close-to-normal high school experience. When she’s rocking stadiums in her long blonde wig, she’s every tween girl’s idol with a fresh-from-the-mall ensemble and post-Avril Lavigne lyrics about independence. At home, her life is a family-friendly melodrama filled with typical teen angst and puppy love. For a time, The Disney Corporation had it made. Hannah & Miley Stewart/Cyrus were on every merchandisable surface possible. But young women grow up. Eventually, the dream bubble would have to burst.

To delicately rupture this fantasy and resolve the uncanniness of the series so that Cyrus could strike out on her own, Disney carefully crafted “The Best of Both Worlds” tour (2007-2008).

Featuring a double bill of Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus, with special guests The Jonas Brothers, the concert is filled with what Tour Director, Kenny Ortega (Newsies, Hocus Pocus, High School Musical 1-3), calls “illusional fun.” Watching the concert documentary Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus: The Best of Both Worlds, which celebrates its fifteenth anniversary this year, we get a sense of how real, complex, and Lynchian the Hannah/Miley phenomenon was.

The illusions pulled on in the concert may be fun, but they have a genuine function. In just under two hours, Miley has to delicately divorce herself from her fabricated persona. This concert has to educate its young audience that there’s a difference between the Hannah/Miley on TV and Miley Cyrus, the singer-performer. To do this, they put on a spectacle of changing identities. Guy Debord’s classic The Society of the Spectacle argues that spectacles are what happen when images overtake identity. Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus: The Best of Both Worlds in Concert is a kind of capitalist meta-spectacle for how choreographs and celebrates a shift between corporately structured and personal identities.

We open with Miley Cyrus warming up in the wig chair. Unlike most other concert documentaries, there’s a clear donning of character. Miley prepares to give some puppet theater: When ready, she’ll put on that classic Lynchian accessory, the blonde wig. So will thousands of young fans (and their dads.)

In just under two hours, Miley has to delicately divorce herself from her fabricated persona.

The blonde wig symbolizes Classic Hollywood in all its glamor and disguise. It allures as much as it conceals. It is also the synthesis of the white supremacist patriarchy’s fascination and fear of white women — desirable yet untouchable. Rita (Laura Harring) shivers with this paradox in Mulholland Dr. when she puts on a blonde wig to match Betty (Naomi Watts.) She hopes to attract an answer to her identity while concealing the one she doesn’t know.

Hannah Montana’s wig use is similar, but hers feels like a glamor charm and a modesty covering, something to inspire while also reflecting angelic chastity.

It’s a good thing Hannah Montana gets such a visually explosive entrance, because little can be heard over the piercing collective ecstatic scream of thousands of fans melting in front of their idol. Miley performs Hannah Montana’s lite-punk princess routine with her utmost, skipping, jumping, and fist-pumping all over the place. Hannah’s songs about striking out on your own, dreaming your dreams, and living an authentic life are inspiring, but also ironic, given that the purpose of the concert is to put Hannah to bed and let Miley Cyrus follow her dreams of being a singer under her own name, free from Disney’s moral and legal control. Though she knows it’s the beginning of the end for Hannah Montana—she still had a feature film and 1.5 seasons left of the show—Cyrus is determined to sell every last drop of the fantasy to her adoring masses.

Some of the older fans might understand what’s happening, but from the documentary, it’s clear most of the audience is here for Hannah. One thing’s for sure, no one is here for Miley Stewart. She—like Rita in Mulholland Drive or Madeline in Twin Peaks—is a mirror image, not an opposite. As much as this concert is about resolving the Hannah Montana mirage, it’s more about killing any notion that Miley Stewart and Miley Cyrus are the same person. Trapped in the classic Lynchian standoff between Blonde and Brunette, Miley Stewart is the true fantasy that must give way to reality.

To accomplish this, Ortega and crew introduce a third double. During the middle act performance by fellow Disney products, The Jonas Brothers, Hannah sings her verse before joining her dancers in the back. In the frenzy that is the Jonas brand of pop-rock, Hannah disappears backstage. Then, a dancer wearing the same costume and wig comes out to finish the number. Miley Stewart dissolves by sleight of hand.

Miley—like Rita in Mulholland Drive or Madeline in Twin Peaks—is a mirror image, not an opposite.

But this is no ordinary costume change. It’s standard in pop concerts for the diva to leave during a song and come out with a new ensemble a little later. Adding the double is a deliberate choice to help the audience keep Hannah Montana and Miley Cyrus separate. This led to some drama, with folks claiming it meant Cyrus was lip-syncing the whole time. The Nancy Drews were so dialed in they didn’t realize they had just witnessed a murder.

The final act opens with “are you ready to meet Miley Cyrus?!” Like Mulholland Drive or Twin Peaks’ multiple Kyle McLaughlins, Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus: The Best of Both Words proceeds from the wigged-double to the twist of a third or split self. Though the tour is based on a double disc album (half Hannah / half Miley Cyrus) and her fans are familiar with her “edgier” lyrics, she has a mere 20 minutes to establish her “self” and assuage any fears or uncertainties her fans may have. And then she has to do it again, repeatedly reintroducing herself from city to city.

The Nancy Drews were so dialed in they didn’t realize they had just witnessed a murder.

Now that Hannah & Miley have broken out of their 2008 confines, we understand how bizarre the phenomenon was. While several artists have had to differentiate themselves between their onscreen persona and their previous acts, few have had their identity and character so closely immeshed. She not only had to separate herself from her on-screen persona (while sharing concert billing with said persona), she also had to distance herself from her character’s off-stage persona, Miley Stewart. As with all doppelgangers, only one can survive.

As students of David Lynch, we know that the only way for women to resolve the problems of the double is through sex. Betty and Rita get it on in Mulholland Drive, and the men of Twin Peaks sure get an erotic charge out of seeing Madeline after her cousin Laura’s death. The songs that Miley Cyrus chooses to sing for her “introduction” are noticeably more angry and physical. Though it may have shocked some puritanical parents, that Miley would go on to have a very public embrace of her sexuality should come as no surprise.

She’s not the first, either. Lindsay Lohan went through a similar thing to get rid of her Disney split self. For Miley, embracing her body and desires indicated a clear and irrevocable break from Disney. To bury Miley Stewart forever, sex became essential. It is beyond the scope of this piece and David Lynch to talk about how the industry mandates young white women to exploit Blackness as a way of announcing and performing sexuality. We should note that already in Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus (especially in the post-Latin Explosion song “Let’s Dance”) race play was starting to creep in.

Related: Lindsay Lohan’s Split Selves

It may seem strange to talk about David Lynch outside of his oeuvre, but any so-called “master” should offer lessons we can carry without outside of their work. Lynch’s works—like Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks—contain useful observations about how doubles function in our society, Hollywood’s duplicitous role in making spectacles, and how sex integrates with social persona. By being a fan of David Lynch, I found richer things to appreciate in the Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus concert documentary. It was a Lynchian moment in real life.

Under the Lynchian lens, Hannah Montana & Miley Cyrus: The Best of Both Worlds Concert indulges in revelations often discredited or overlooked by adult critics. All it takes is a genuine sense of appreciation to see them. As Miley says in her song “Start All Over,” it’s often best to go “out of the fire and into the fire.” Walk with me.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox