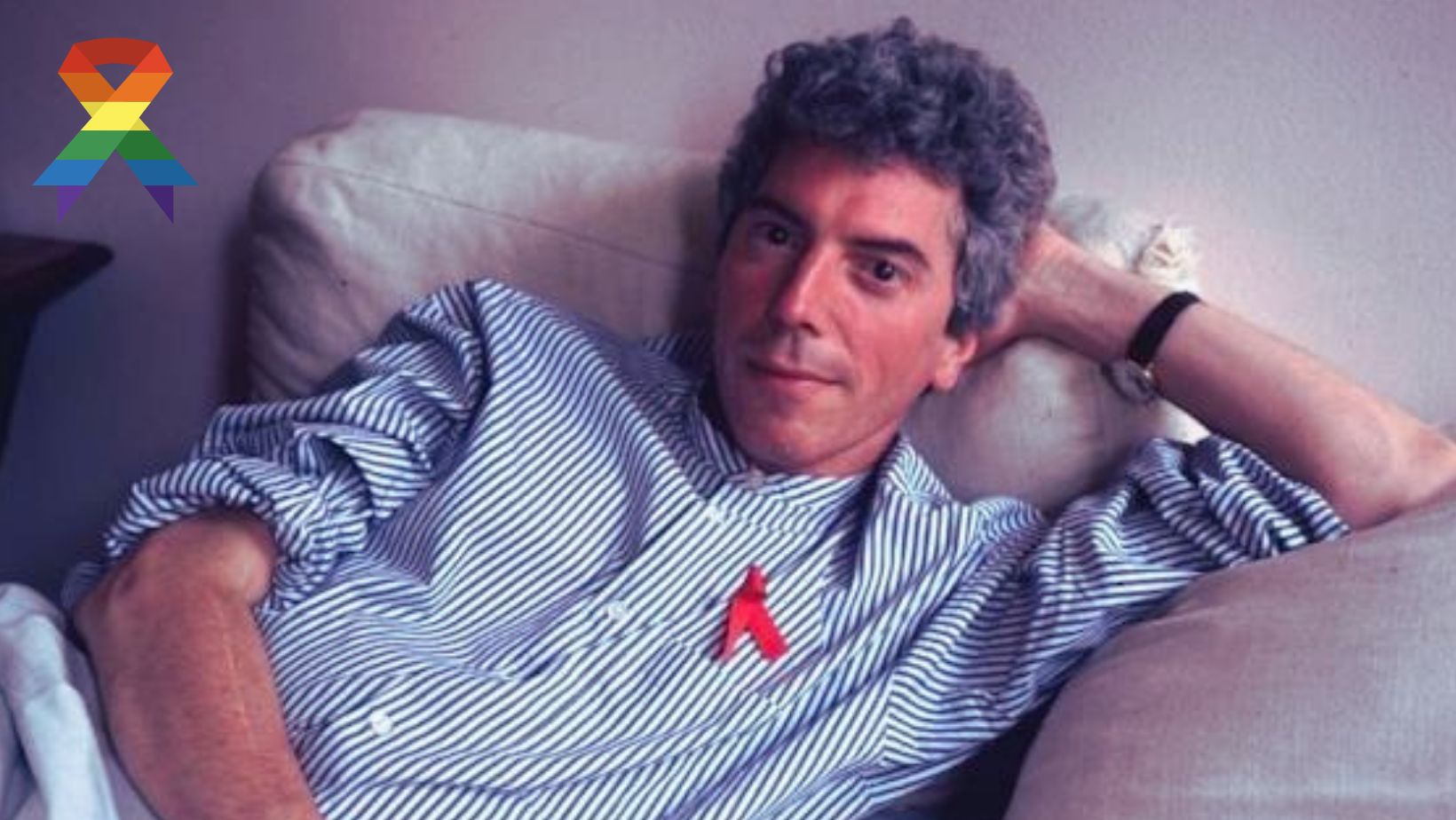

Patrick O’Connell, the artist and activist whom the New York Times reports passed away on March 23rd to AIDS-related causes, wanted to be seen. He wanted his friends, cohorts, and people he had never met to be seen. This had nothing to do with a desire for fame and fortune—sadly, it was a much more basic desire than that.

He was diagnosed as HIV-positive in the mid-eighties, during a time when so many people he knew were rapidly dying of the same prognosis. As he described it, “The East Village art scene felt like it was disappearing overnight because of AIDS.” But it wasn’t just the disease that was causing these people to disappear from sight. It was the silence of the Reagan administration, the invisible nature of the virus, the general public stigma. To this end, he made it his mission to spread awareness in what ways he could, to make sure that even if he and the other AIDS patients would ultimately succumb to this disease, they would not be erased by it.

Patrick O’Connell was a lifelong patron of the arts, directing the Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center in Buffalo and later involved with the alternative NYC gallery Artists Space. In 1989, following his diagnosis, he turned his artistic eye towards advocacy as the founding director of Visual AIDS, an organization with the goal of supporting HIV+ artists and stirring up public consciousness of the disease. He would do so through a series of campaigns that interrupted public life with representations of the toll of AIDS.

On December 1st, 1989, in conjunction with the second World AIDS Day, Visual AIDS coordinated the Day Without Art. According to the Visual AIDS website, over 800 art organizations participated, covering up works of art with a black shroud to represent the artists lost to AIDS. Some artwork was missing altogether, replaced with resources about the virus and sexual health. The Day Without Art has been repeated annually, eventually rebranding as the Day With(out) Art to highlight the people still living with HIV. Visual AIDS would follow this up with Night Without Lights, Electric Blanket, and Every Ten Minutes.

It was perhaps the smallest of these visual campaigns, a simple red ribbon, that would become one of the most brazen feats of Patrick O’Connell’s legacy. At the time, there were other ribbons floating around, notably the yellow ribbon for the Gulf War. O’Connell admired these symbols for their versatility of meaning and for their simplicity—they gave people an easy way to participate in advocacy and awareness. He reflected in a 1992 interview with the Times, “People want to say something, not necessarily with anger and confrontation all the time. This allows them. And even if it is only an easy first step, that’s great with me. It won’t be their last.”

For his ribbon, he chose the color red, knowing the bold color would stand out on any garment (knowing also it would be associated with both love and blood). Together with Visual AIDS, he started the Ribbon Project and organized the handmade construction of thousands of red ribbons. He and his “ribbon bees” then hit the streets handing them out. They used their connections to get ribbons onto as many influential lapels as they could, most notably in the 1991 Tony Awards where Jeremy Irons graced television screens across the nation wearing a red ribbon. Other celebrities followed suit, and the red ribbon was soon showing up on everything from the Grammys to the Oscars. As a result, the red ribbon became thoroughly established as the international symbol of AIDS advocacy in the early 1990s.

After living with HIV for 40 years, O’Connell passed at the age of 67, leaving behind an indelible legacy of activism and hard-fought visibility. But often forgotten in the histories of brave activists is the little solace these struggles brought to their personal tragedies. As he told the BBC, “I would give anything, I would give back all this attention if I hadn’t lived through these decades of AIDS.”

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox