My cousin Haley wobbles out of our Winona canoe onto the muddy riverbank of the Green River as the tamarisk rustles in the hot wind.

We had spent the morning paddling the maze of Labyrinth Canyon as a part of a four day self-guided backcountry river journey that winds us from Ruby Ranch to our pick up at Mineral Bottom, nearly an hour and a half outside of Moab, Utah.

I waggle from the canoe, slipping in the mud that scoots below my Tevas. It is thick, river bottom sediment. I secure the stern of our canoe to a young cottonwood with a rope in a tight two half hitch and the bow to one of our 10 gallon water jugs for extra security. Our canoe is our lifeboat, we would be lost as a river running into an unknown sea if it were to catch the current and float away.

We snag our water bottles, a few snacks, and daypacks from the basin of the canoe and set off to explore one of the river’s remote side canyons in search of thousand year old petroglyphs we were told about by our outfitter, Kevin at Moab Rafting and Canoe Company.

The tamarisks are thick before us and smell like hay and honey. They stroke and tickle us as we ford through them on a little game trail (that I assume was cut by desert bighorn sheep.) It leads us into a separate dry canyon off Labyrinth Canyon — a canyon that once held the Green River within it, before its oxbow gave way and the river shortcut itself by miles.

In the clearing beyond the tamarisk, the canyon called Horseshoe stretches wide as taffy. Orange-red walls soar towards the cornflower blue sky. It is one of my favorite color contrasts — one imprinted in my mind when my eyes shut. It is a mood, it is a vibe, it is some serious Georgia O’Keeffe “Red Hills and Sky” (1945).

The greasebrush thickens, the faint trail narrows, and Haley kindly cuts me off, like she did when I came out to her one tequila heavy night in college, before she proceeded to steal the thunder and come out to me.

I say this in jest — we’ve been eminent in one another’s lives as we embarked on our own queer voyages — yes, through vastly different landscapes — but like the canyonlands of Utah and the LaSalle Mountains mountains above them, topography belonging to the same southwestern region.

She hikes ahead of me wearing her bikini top and pants and Chacos and a pair of very bro-y Oakley wrap-arounds with blue tints and a wide straw sunhat that keeps the sun off her face and lightly freckled shoulders. Her body is covered in the dirt of the canyon from all the swimming, from all the sleeping below the full moon on sandbars, from gusts of wind that have blown the little red particles onto her skin that stick like sand art. It is our third day of our canoe trip and we are dirty, happy, desert rats.

High noon blasts 100 degree sunshine onto the canyon floor as we wander further from the lush Green River. Cacti begin to punctuate the landscapes — mostly beavertail and claret cup — it is September, and the grasses are brown and gold and we fear the sun drying us up, too. We straight line for the thin yard-wide sliver of shade the canyon wall provides.

We mosey along the debris of fallen slabs and boulders in the shade where it is a full ten degrees cooler. Haley walks ahead of me and wistfully brushes a fallen boulder with her fingertips.

“Whoa,” she says.

“What?”

“Look.”

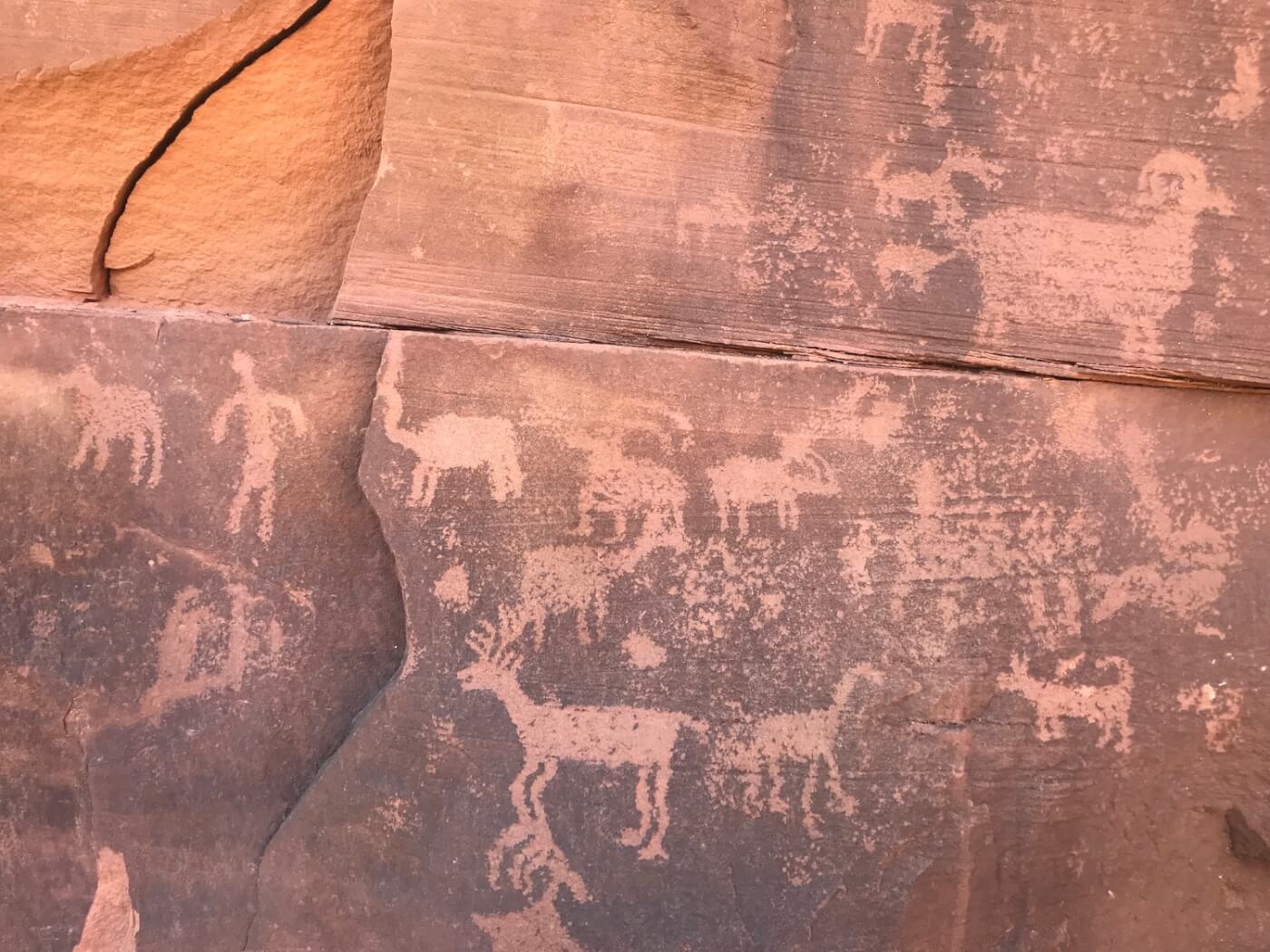

There, ten feet in front of us, is a gallery of petroglyphs.

The rock has blackened around the carved shapes, but they remain orange, reddish, and bright as ever. It is as if they were pressed onto the rock that very day. But they were not, they were etched on the rock face a thousand or more years ago by the Fremont people, a people predating the Utes, Navajo, and Paiutes who later called the region home.

On the walls of the Glen Canyon Group rock are an abundance of sheep — identified by their curly horns, much like the ones whose trails we followed from the river and led us to the gallery. Beside the sheep, there are deer with pointed antlers, there are little resilient coyotes, there are some animals we can’t fully make out, a zoomorph, as well as two or three human figures sprinkled throughout — a minority among the masses of fauna.

We as a society are used to seeing sites like this in museums, removed from their original homes. But here in the canyon far away from anything, they rest largely undisturbed. They are among the hundreds of thousands of pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings) living, existing, and dancing on the geology of the Southwest.

Their common viewers are the white-throated swifts, golden eagles, and turkey vultures soaring in circles above them. There are no ropes or railings, no signs that read do not touch, no museum employee watching your every move telling you to wear your backpack in the front — these petroglyphs are over a thousand years old and lay completely exposed to the elements and rare common passerby. They make the U.S. Constitution look spry and puerile. Their age constellates respect and we do not touch.

Many times when we travel, explore, camp, and backpack we forget to acknowledge the land’s original residents — typically we don’t even know the history of the places we visit, even when it stares us in the face.

We ignore past traumas of landscapes and the peoples who lived there because they make us, as non-native Americans, Australians, Canadians, and every other nation guilty of colonialism uncomfortable. Most of the time, this history has been erased, moved, eradicated, and displaced to make way for whiteness and guiltless consciouses.

That’s one of the reasons the Southwest is so significant; in many ways it is a largely unprotected, unwatched museum with evidence of first peoples literally carved into the landscape. Petroglyphs on the Kayenta and pictographs painted on the Navajo Sandstone tell us stories and speak a poetry of existence.

This brings us to territory acknowledgement — a practice gaining popularity in many civic events (especially in Canada) to help undo the erasure of colonialism. A site, Native Land, defines the process, “Territory acknowledgement is a way that people insert an awareness of Indigenous presence and land rights in everyday life.”

The act to many is “a small but essential step toward reconciliation”.

Native Land helps users generally identify indigenous territories that they are traveling to or living upon by location of zip code so the territory can be properly acknowledged. If I type in my zip code in Los Angeles, it shows the territory of the Tongva.

And when I pinpoint our exact location of drop in on the Green River, it shows the Ute, though, after reading about the area, I also understand the area to also have reports belonging to the Diné and Paiutes. So, outloud on the banks of the Green, I acknowledged the canyon, the river, and the territory of the Utes, Diné, Paiutes and the many other ancestral peoples that came before them.

When I first heard of the practice — as a white, cis, queer man — I felt that it wasn’t my place to perform land acknowledgments. That in an attempt to be respectful as I passed through the southwest and acknowledged the land that I would be seen as inauthentic and phony, that I would be stepping on toes and doing more harm than good.

It wasn’t until I read Chelsea Vowel’s Beyond Territorial Acknowledgements that I began to understand the practice better. A part of the text reads,“[land acknowledgements] can be transformative acts that to some extent undo Indigenous erasure…The fact of Indigenous presence should force non-Indigenous peoples to confront their own place on these lands.”

The key words are to some extent. Land acknowledgments are just the beginning.

They are the bare minimum on the road toward a societal reconciliation that many believe will help combat the further erasure of the history of indigenous peoples. A land acknowledgment before a trip makes non-natives grapple with the past, their history and lineage and ancestors, and again, as Vowel wrote, “confront their own place on these lands.”

It makes us ask, what is the backpacker’s place? What is the queer nature lover’s place? What is the birdwatcher’s, the alpinist’s, the Instagramer’s, the ranch owner’s, or the road tripper’s place? How can we address our privilege constructively and help one another in our common journey to true allegiance for our land, its history, and the preservation of it and of all the cultures that call it home?

This is something we often forgotten even in the outdoor community, even though we spend intimate time on these lands. Coming across petroglyphs and pictographs all over the southwest have always been mandatory land acknowledgments themselves to me — how could one not acknowledge and respect the people who once called this place I recreate in, home? How could I not feel but a small tresspasser? It is only now that I vocalize this acknowledgment and when writing, do all I can in telling the story of a place, beginning with its first peoples.

Unfortunately, little is being done by our federal government to protect the pictographs, petroglyphs, ruins, or territorial lands of North America’s indigenous people.

Before our trip through Labyrinth Canyon, I read about a man who scratched his and his wife’s initials (surrounded by a love heart) onto the iconic Corona Arch, outside of Moab, looting in Bears Ears National Monument, as well as over 374 reports of vandalism (this year alone) in nearby Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument that were logged on the app Terra Truth, which helps users show exact locations of vandalism, wreckage, illegal off-roading, and looting on public lands.

The increase in these comes along at the same time as the shrinking of many public lands (like Bear Ears and Grand Staircase) were authorized by the Trump Administration in December 2017, led by former Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, who resigned in December 2018 with over 17 active ethics investigations to his name.

He departed officially in January, 2nd, during the government shutdown, as understaffed national parks like Joshua Tree and Yosemite are being littered with human feces, trash, and vandalism, with no federal employees to look after basic facilities.

By shrinking many of Utah’s monuments, the Trump administration literally cleared the road for many new oil, gas, and coal leases to be purchased. Their greenlighting of these leases and shrinking of monuments has left more than a million of acres of Bears Ears (the monument was shrunk from 1.35 million acres to 201,876 acres) exposed and without protection. Take for instance, the illustrious petroglyphs in Moqui Canyon, the cliff dwellings in the Dark Canyon Wilderness, or the grand Cedar Mesa (which is said to contain 56,000 archealogical sites, some of which date back to the Clovis people who lived in the area over 12,000 years ago), as well as many other culturally significant sites.

Next to the petroglyphs Haley and I came across in Labyrinth, not far from Bears Ears, were the markings of 20th century visitors J.A. Ross, Ella E.V. Ross, Bennie J. Ross (1903), and Noel Jackson (1927). Beside these were seemingly recent carvings left other canoe trippers thinking they could leave their own mark beside the petroglyphs, in the middle of nowhere, with nothing but the tamarisk watching.

There was even another damn love heart scratched into the wall as well as a couple of other chaotic cat scratches for no purpose at all but recklessness.

This kind of vandalism on our public lands, especially in Four Corners region of our country with rich indigenous significance, history, and archaeological evidence show the Trump Administration’s aggressive disrespect and harm towards our indigenous peoples and our environment. It shows the administration’s 21rst century brand of colonialism (and white nationalism?) that continues to erase the proof of indigenous territories (and existence) from these landscapes.

The vandalism, selling, and mismanagement of our public lands also potentially erases the documentation of all historic queerness in the region. As I wrote about in “A Queer Ode For Bears Ears National Monument,” “Connell O’Donovan, an administrator at UC Santa Cruz and a writer focusing on queer Mormon history, found a petroglyph twenty years ago while living in Moab. He describes the petroglyph as “two men with erections reaching out to embrace each other; it dates to circa 800 CE.”

This is just one known instance of the documentation of what he categorizes through a queer lense as a possibility of queer archaeology. There is very little written on the subject. Perhaps, there are even more queer petroglyphs and pictographs to be discovered in the vast landscapes of the Southwest. How can we know if we sell culturally significant land to leasers? Shouldn’t we want to preserve the history the human race, no matter what we look/ed like, where we live/d, or who we love/d?

If vandalism and destruction of our public lands continue, there will be erasure to all of our histories. This is why it is important to know what land we are on, acknowledge exactly who we are, and follow the guidelines of leave no trace as we respectfully travel on land that was taken from indigenous territories.

How will we ever reconcile and unite if we erase each other, forget who we are, and dismiss all the terror and wonder we’ve ever done?

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox