LGBTQ people have been heavily involved with early iterations of all kinds of music yet are rarely included in documentaries dedicated to the history of genres like punk, glam rock, or riot grrrl. Often, their inclusions come as sidenotes or brief mentions, as directors would be remiss not to include queer and trans songwriters, artists, and musicians who were integral to these cultural moments and movements. Yony Leyser’s Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution is a departure from these other offerings, allowing the pioneers of queer punk art to celebrate their underpraised work and influence.

Leyser himself wasn’t aware of the trajectory he would eventually detail in his film. At 34, he was born at the same time queercore was emerging. Though queer and trans people like Jayne County had been involved with the beginning of punk in the ’70s, queercore itself didn’t get coined until the mid-’80s, when artists and filmmakers Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones started publishing zines (most notably J.D.’s) using the word.

Leyser’s documentary, in theaters in L.A. and New York this weekend, highlights how LaBruce and Jones spawned an international movement by simply asserting that one already existed. The two former friends and collaborators (Leyser says they haven’t been on speaking terms since 1991) lived and worked in Toronto, where their published work and films promoted their ideals. Their DIY aesthetic and in-your-face approach to sexual liberation was direct inspiration to riot grrrls like Kathleen Hanna who, in Queercore, shares that the movement was both a precursor to riot grrrl as well as a concurrent kin.

“[Queercore] wasn’t so well documented,” Leyser told INTO. “There was the riot grrrl documentary that came out as a documentary about Kathleen Hanna, but queercore somehow went under the radar because mainstream media didn’t pick it up. So I wanted to make a film so we could re-live a certain experience that they didn’t have the chance to because they were too young or too old or didn’t know about it, and to remind us that there’s still so many radical possibilities to our existence, and in embracing our outsiderness and embracing the rejection that we felt from society. We can create great art. “

One of the primary concepts of queercore was the provocation and rejection of mainstream gay culture as well as the accepted heteronormativity of punk culture. LaBruce utilized swastikas and Nazi imagery in attempts to instigate conversations and outrage (“He’s showing he’s this feminist fag fairy wearing swastikas to confuse people, to confuse the neo-Nazis … and ward off Nazi punks,” Leyser said). Jones embraced the idea of man-hating lesbians and matriarchal paradigms. And their collaborators and followers followed suit, with bands like Pansy Division, Tribe 8, and Team Dresch bringing queercore to America and, eventually, inspiring a new generation of artists to fuse their sexual and gender identities with their artistry and anger to create inspired new work that not only spoke to queers and trans people, but centered them in the process.

“I think it definitely benefited queer culture by keeping it political and radical and open and accepting to people on the margins rather than trying to fit in,” Leyser said. “And as far as punk culture, I think the film exposes the connection between gay and punk.”

He notes that gay bars were some of the first to allow punks entry at a time when they were seen as problematic at other establishments, and that punk bands were some of the first to embrace trans and queer identities.

“You look at Lou Reed, you look at Iggy Pop, you look at Patti Smith — that was the idea,” Leyser says. “Joey Ramone was a hustler. The birth of queer culture, in a modern sense, was rooted in punk and punk was rooted in queer culture. So I think in the film, I’m arguing that most people associate punk with machismo, with macho ’80s hardcore men, but actually the truth is that early, original punks’ ethos was very queer and it was the birth of the queer setting.”

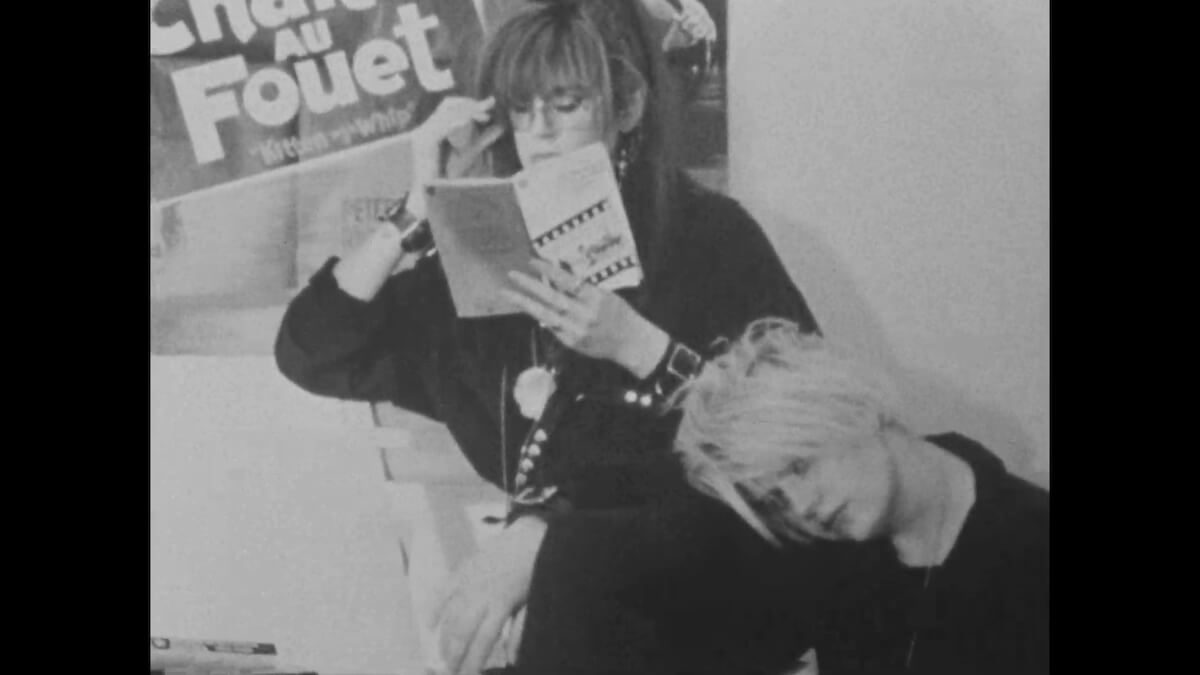

Queercore employs interviews with LaBruce and Jones alongside Hanna as well as those who were a part of or adjacent to the movement: John Waters, Mx. Justin Vivian Bond, Kim Gordon, Patty Schemel, and Lynne Breedlove all share memories amidst clips from live shows, film clips, zine pages, and photographs. The film legitimizes a scene built out of countercultural queer art, and the community it helped to build — one that still exists under the radar.

Leyser said he created zines and came up in Chicago, where he didn’t initially find a marriage of the two subcultures.

“In high school and the beginning of university, I was a punk,” Leyser said. “I knew about a kind of gay culture — there was Boys Town, the gay neighborhood. I embraced more of the punk community, but I didn’t know any gay people … so when I learned about queercore, it was a real eye opening. I feel like I found kind of family, even though I didn’t know contemporaries at the time, because I was a generation after them. I was excited to learn that it existed and there was that possibility. I discovered there was some really radical queers — there was this group called Bash Back that was doing these really radical anarchist activities from a queer housing collective in Logan Square. And I lived in Lawrence, Kansas for a while — there was an anarchist collective there called Solidarity and they were doing all these kind of queer radical events like Food Not Bombs — Queers Not Bombs. So, it was going on but it was kind of under the margins, and it was before the internet. … We had to kind of know the right people.”

Leyser, who also made zines and toured with Michelle Tea’s queer punk collective Sister Spit, eventually found a chosen family that has distinct roots in queercore and the establishing of that radical community.

“The story that really resonated with me was the relationship between G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce, because I thought it was a universal story for two teenagers to start a revolution from their bedroom,” Leyser said. “It’s exactly what riot grrrl did and I thought that was the universal story.”

Because LaBruce and Jones are no longer on good terms, Queercore feels somewhat bittersweet. But Leyser says they were both interested in the documentation of their work and the work of others, and wanted to be a part of it nonetheless — just not in the same room, of course.

Still, the story of Queercore, he hopes, will resonate with LGBTQs his age and younger who might be unaware of the kind of queer influence and inspiration happening outside of mainstream visibility.

“Queers throughout history have been great instigators of activism and art in culture and the underground and nightlife, and to have the great ability to do so,” Leyser said. “Like Judith Halberstam says in her book, queers can even transcend time — they just reject mainstream culture. So I think the younger generation has the ability — if they are able to create these communities — and I hope that the film sheds some light and also helps destroy the macho image of punk that people have.”

Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution opens in New York and L.A. on September 28.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox