In the 1990s, young and angry was the norm, especially for queer kids. While the small-town queers I knew had mostly found our tribe with the punks and goths—and maybe even with the theater kids—we were still operating on some secret level, having no true points of reference to guide us into gay adulthood. We grasped at any coded queerness we could find. This was before the Internet, so we were mostly on our own, except for porn and a lot of AIDS narratives and hardly much else. The culture made it clear: Being queer was not ok. But every once in a while, something came along and gave us—at least some of us—the knowledge that we weren’t totally alone out there.

These moments happened largely at the movies. As a teen, films centered on disenfranchised youth spoke deeply to me, and one of the most vivid entries in the genre was Gregg Araki’s The Doom Generation. It was about young people on the road, on the run, lost in the confusing and arid landscape of another American city. But it was more than that: the film was a punk rock, queer, violent, dark comedy that put three of my favorite things on screen; alternative music, punk style laced with homosexuality, and a Parker Posey cameo.

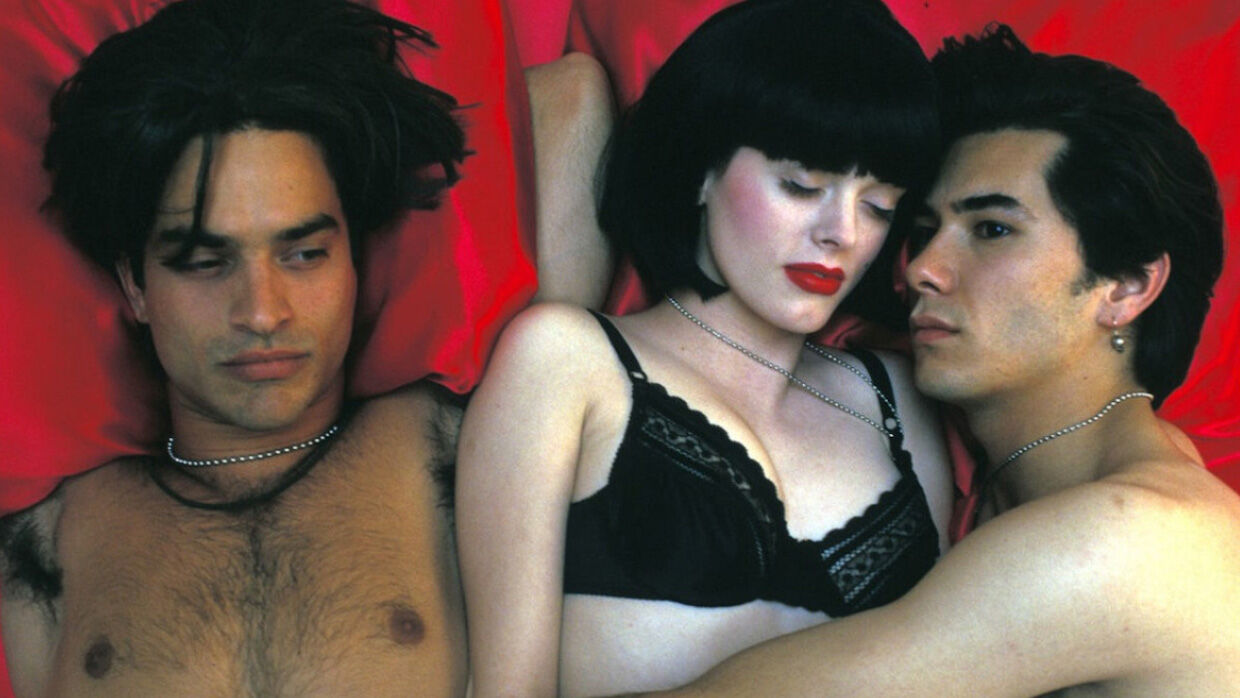

From the film’s first frame, we’re off to the races. The opening credits announce that this will be “A Heterosexual Movie by Gregg Araki,” a nod to exactly how the filmmaker had to market his work to get it funded. But make no mistake: a heterosexual movie The Doom Generation ain’t. Araki handles the sexual aspect of the film—involving a devil’s threesome—in a way that feels so uncannily familiar to the bicurious viewer that it still feels shocking today. When Amy Blue (Rose McGowan) announces she’s bored with everything and takes off on an apocalyptic bender, she takes her boyfriend Jordan (James Duval) along for the ride. But when the pair run into the troubled, violent drifter Xavier (Jonathon Schaech) things get real horny, real fast. Jordan and Xavier immediately develop a sexual tension between them, with Xavier lingering close to Jordan every few scenes, in anticipation of a kiss. The tension is almost played for comedy, but there is something undeniably hot about two unshowered men’s faces consistently filling up the screen. Xavier’s character is an anything-goes, wild-at-heart maniac, and Jordan is the sensitive emo type. Jordan is not opposed to the intimacy of being with a guy so much as he is ignorant to what such an encounter could mean. Basically it’s every queer kid’s adolescent journey, wrapped in an apocalyptic fever dream, with Rose McGowan thrown in.

Related:

Parker Posey Will Always Be My Queer Icon

She’s one for the weirdos: a diva with heart and grit, who you just might see in a dive bar on 14th Street near NYU.

While we’re on the subject of McGowen, I’ll just say it: no one delivers the word “f*ck” quite like her. She nails every single one-liner so perfectly that she nearly steals the entire film. Amy is a strong, self-assured young woman who carries a sadness about her. This tristesse, combined with her no-bullsh*t, hard outer shell creates the most relatable character in any movie I can recall from that time. With her jet black bob and array of novelty sunglasses, she’s Louise Brooks’s Lulu for the MTV generation. And while trouble finds her at every stop, she’s the one who ends up saving the boys every time. Driven by both pragmatism and desire, and an endless penchant for dry, wicked sarcasm, she alone knows the path forward through this hell they’re living in. Her journey—in all its chaotic beauty—is the emotional essence of the film to me.

At the time, I also didn’t know this was the second film in Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse trilogy, the first being Totally Fucked Up (1993) and the third, Nowhere (1997). As always with Araki, there’s a self-assured style to the movie that makes it worth the journey, even during its gnarlier moments. From Doom Generation’s starkly lighted set pieces—hotel rooms glowing in Dario Argento red—to the Warhol tinfoil bars, second-hand, tattered costumes, and brightly colored lips, there’s never a question about the director’s queer intention for this “heterosexual” film. The movie oozes arthouse, referencing everything from Kubrick to Penelope Spheris and cheap horror movies from the local video store. It’s an on-a-budget lush, stark, and oftentimes beautiful, film.

The soundtrack, too, has to be given some credit here. Featuring Cocteau Twins, Slowdive, Lush, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Nine Inch Nails, the lineup sounded as if Araki had asked me personally what music I’d like to hear in the movie. And with cameos from Hollywood fringe performers like my queen Parker Posey (spouting in a lesbian rage “I’m going to lop his dick off like a chicken head,”) to Perry Farrell of Jane’s Addiction, Hollywood Madame Heidi Fleiss, Margaret Cho, and more, it becomes clear that this movie is about outsiders in every way.

As one of the truly queer punk movies of all time, The Doom Generation isn’t universally loved. It’s a little too offbeat for that, with its violent, unapologetic sexuality and mid-90s attitide. It’s every uncool parent’s worst nightmare, and that made me love it even more. I remember when I showed it to a friend of mine and her mom walked in and was absolutely appalled. It gave me such a sense of pride. It gave me hope that other people out there did love the same things I did, in the way in which I also loved them. Most of all, it showed me that being a homo was nothing if not cool.

At this year’s Sundance screening of a restored cut of the film, Araki said: “…I noticed in all of my movies from the ‘90s, there’s a gay bashing. There is this sense of danger to being queer and being the outsider, and I think that’s why it resonated so much with the kids and the outsiders. There is that sense of the outsiders being fucking killed that’s happening even today.”

He continued: “The sad part is, there are still gay kids and trans kids getting killed by these Nazis. The first screening of The Doom Generation was so intense. Nobody had ever seen it before. And during that ending scene, people were just walking out, so in shock. It is a really intense scene, but that’s the world we live in.”

I revisit The Doom Generation every couple of years – sometimes for nostalgia, sometimes to remind myself how cool movies can be, but mostly because I just love it for all that it is. It came at a time in my life when the world felt weird, cruel, unable to resolve the 90s teenage ennui everyone my age had developed. Things were harsh, music was loud, and to me, humanity had already largely started to look like a lost cause. 1995 was a year where we craved style with our substance, even if we knew no one was coming to save us.

The Doom Generation influenced me in so many ways. The film’s queer and edgy narrative was only half of its appeal. It’s a time capsule for those of us that gravitated toward the counterculture. In the world Araki created for us, you could be a queer and nobody cared. Was it a fantasy? Yes, a fact brazenly, violently underscored in the film’s last scene, featuring bloodthirsty neo-nazis taking revenge on our queeros while the National Anthem darkly plays.

I guess some things never change. ♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox