One of the frustrating things about growing older is seeing the history you lived through get distorted. The inaccuracies range from the trivial (“No one in the ’80s wore their hair like that”) to serious errors (one of the exact parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the AIDS crisis is that the number of deaths were undercounted. The actual death toll was higher). Queer and AIDS activism in the early ’90s were a whirlwind even for those of us who were there (maybe especially for us!), so having an insider’s view is crucial.

Sarah Schulman, the author of Let the Record Show, a new, definitive history of the direct action group the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP), was a member of the group’s New York branch in its late ’80s-early ’90s heyday. She’s also the co-director of The ACT UP Oral History Project, composed of nearly 200 long interviews of former members of ACT UP New York, compiled over 17 years. These excerpts make up the bulk of Record.

Schulman, the writer of eighteen previous books, provides a framework for these voices, but rarely puts forth her own experiences–except in the introduction and conclusion, and the full interviews are linked as online PDFs along with short clips of audio or video. With each interview snippet centered around an event or time period, the text, with its contrasting points of view (most apparent between men and women, as well as white people and people of color) becomes a kind of ACT UP meeting itself, with each person saying their piece, sometimes contradicted by the person whose words come immediately after or before. The difference is that in print, Schulman can cut members off before they go on too long.

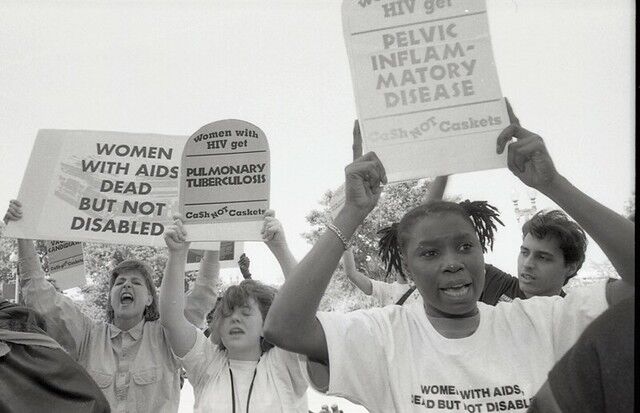

The book is so densely populated with revelations and resonance that to point out only a few examples is difficult. One of the most well-known players in the current pandemic, Anthony Fauci, is, depending on who’s speaking, either a savior (for his role in getting the life-saving drug combination approved) or a villain. During a meeting with ACT UP women, including Linda Meredith, to get the definition of AIDS changed so it covered women’s symptoms, he tells them “I have an agreement with the men in ACT UP that they don’t speak to me in that way.” Meredith counters, “I’ve never even met you before. How could we possibly have that agreement?” In the introduction, Schulman explains only one woman with HIV in ACT UP New York survived, and she wouldn’t agree to an interview because some members of her family still don’t know her status.

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

Most of Schulman’s previous books have been novels. Tellingly, the arc and sweep of this volume mimic the best kind of fiction. We learn that some of the HIV-positive, white, privileged gay men of the group split off from the others to work with (and receive money from) pharmaceutical companies and to cultivate closer relationships with bureaucrats like Anthony Fauci. Both, in the process, hastened the arrival of the drug combination that would make AIDS a manageable illness for many, but also cut off those who couldn’t afford these drugs or health insurance.

Plenty of other people in ACT UP went into nonprofit AIDS services (as I did, for a time) only to see the wisdom of ACT UP never deigning to lobby for those services. As Garance Franke-Ruta says, “If you don’t yet have any inkling of what’s possible or impossible or proper or improper, then you’re much more likely to do things that actually wind up moving the bounds of the possible.” As part of nonprofits, individual ACT UP-pers have their uncompromising vision limited by the narrower scope of these organizations, no matter how many good works they do.

Schulman writes, “Both Maxine (Wolfe) and Mark (Harrington) illustrated that leaders, in activist movements, are the people who do the most work.” Later she adds, “And they were both relentless” Like a lot of other members of ACT UP, Ann Northrop uses her experience in the straight world (which for Northrop included a stint at CBS News) as she advises members on how to not talk “to the media” but “through the media”. Rick Loftus, an ACT UP member who became a researcher, reiterates the value of ACT UP’s non-hierarchical nature. “I would go back to my lab and say, Well you know, blah, blah, blah, blah, and I would present something that some bartender had observed at an (ACT UP working group) T&D meeting or treatment committee meeting, and you’d have this bigwig fronts-of-the-newspapers, doctor-scientist say, Really? Oh my God, what an interesting idea —I’d never thought of that, but that’s true, isn’t it? ”

Record leaves us with some striking moments highlighting the many who died. While sharing a ride to Washington for an action, a young “oversensitive” legal coordinator, Karen Moulding, plays a game of “I Have”, a contest of sexual experience, with the older gay men in the car. She wins. Talking to Shulman, she recalls, “And I remember at the end of this game, Bob Rafsky—there’s a silence, and he goes, Karen, you’ve just found yourself some newfound respect. We’ll never look at you the same way again.” In the next sentence she remembers his memorial. Women’s health advocate Risa Denenberg, in her time in ACT UP, befriends one of the more contentious members, Jon Greenberg. When she scattered his cremains, “she asked everyone to make Jon’s wishes come true and eat some of his ashes. Not everyone would, so she put them in the coleslaw.”♦