Just a few weeks ago, it was announced that Frida Kahlo’s closet would travel outside Mexico for the first time in history, making its way to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum early next year.

This announcement was met with enormous fanfare because the clothing, which was locked away for 50 years following her tragic death in 1954, creates a unique portrait of the excruciating pain she endured throughout her life. There are the beautifully painted medical corsets, which became a necessity after she was involved in a tragic road accident at just 18 years old. There are fringed, scarlet-colored boots, one of which has a stacked heel to disguise the effects of polio, which made her right leg shorter and thinner than her left. There are the flowing, technicolor dresses she wore to simultaneously express pride in her Mexican identity and mask the scars written across her lower body.

Kahlo’s life was famously fraught with pain. Born in Mexico City in 1907, the painter spoke about her “very, very sad” childhood, which escalated in 1913, when she contracted polio at just six years old. This was the first in a series of horrific incidents which forced her into solitude, eventually leading her to find solace in her art. Her ability to turn pain into beauty was both surprising and admirable; her self-portraits in particular won worldwide acclaim for their depictions of strength against adversity. “My painting carries with it the message of pain” remains one of the most famous quotes of her career.

These elements of the painter’s life – the pain, the suffering, the ability to channel them into timeless works of art – are well-documented. Kahlo’s queerness, however, is spoken of less frequently.

It was during her school years (which were delayed due to her polio) that Kahlo nurtured a strong, anti-conservative political identity. At 15 years old, she became one of the first women to be accepted into Mexico’s Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, dedicating herself to education and forming an anti-conservative group named the “Cachuchas,” a small but radical faction dedicated to fighting heteronormativity. This dedication to disrupting the status quo is one which characterizes queerness – in a right-wing world which pushes against minorities, deconstructing what it means to be “normal” is a politically necessary act. In this sense, Kahlo lived an unwaveringly queer life which is often ignored.

Take her clothing, for example. It’s clear that Kahlo used style throughout her life to communicate a strong sense of national identity in particular, but one family portrait shows that she also used three-piece suits, slicked-back hair, and ties to subvert what it means to be a woman. Standing with her eyes fixed on the camera, Kahlo presents herself in stark contrast to the dresses, heels, and dangling jewelry worn by the other women in her family. By playing with clothing choices and indulging her inner drag king, she reveals a desire to deconstruct which is radical even today.

This refusal to conform became a famous part of her personality throughout her career. She was defiant – one iconic example of this defiance came when she was advised not to attend the opening of her own art exhibition due to illness. Instead, she arranged for her bed to be delivered via ambulance to the gallery. She was also quick to call out the snobbery of Paris’ art world as her profile increased globally, fighting against elitism and attitudes of superiority. “They are so damn ‘intellectual’ and rotten that I can’t stand them anymore,” she once exclaimed. “I would rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas than have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.”

Not only was Kahlo queer in terms of her ideology and her determination to subvert conservative culture, her love life was notably queer as well. Her most enduring relationship was with on-again, off-again husband Diego Rivera, a Mexican muralist and self-confessed lothario. In total (they divorced and then re-married in later life), the two were married for more than twenty years, but it was an unconventional relationship from the moment it began. It is said that they would live in houses which were separate but conjoined and each have sex with other people in their respective bedrooms. Kahlo was bisexual and romantically linked with a series of beautiful, subversive women whose names have gone on to become as legendary as her own. Although these whispered stories of high-profile affairs are often salacious and steeped in speculation, they reveal the extent to which her love life broke with convention.

Rivera conducted his own affairs too, one of which was with Kahlo’s younger sister, Cristina. This left the artist heartbroken. Soon after finding out, she painted a picture, ‘A Few Small Nips’, which depicted the aftermath of a husband stabbing his wife 20 times after discovering her betrayal – it’s safe to say that, all of the affairs he conducted, this was the one that hurt.

She later remarried him in 1940 not necessarily as a lover, but as a companion to see her through the final years of her life. “I cannot speak of Diego as my husband because that term, when applied to him, is an absurdity,” she once said. “He never has been, nor will he ever be, anybody’s husband.”

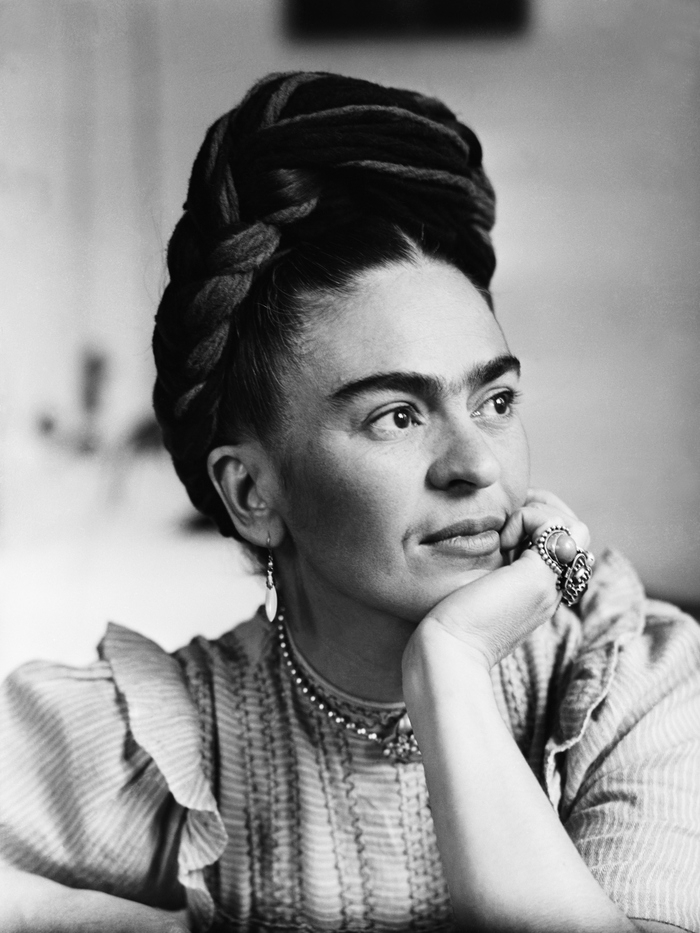

Finally, it’s impossible to write about Kahlo’s legacy without mentioning her famous unibrow. This is the one defining facial feature still recreated at Halloween parties worldwide, styled out by YouTube and Instagram MUAs and discussed in lengthy op-eds which reference its “feral appeal.” Whether intended as political or not, the amount of attention paid to Kahlo’s eyebrow reveals the extent to which beauty standards are ingrained in society. The amount of coverage a few extra hairs can garner is revelatory of the ways that we expect, demand women to fit Eurocentric ideals of “perfection.” Given what we know about the painter’s radical view of the world, it’s likely that the unibrow was a political statement of sorts – instead of plucking, she groomed it with special tools and wore it with unapologetic pride.

Not only is Kahlo queer in her political desire to subvert conservative society, she lived a life free from boundaries and found joy in rallying against expectations. She is a queer icon: one with a heartbreaking story, a timeless body of work, and a complex yet beautiful aesthetic which, even today, still issues a “fuck you” to societal norms in terms of its singularity.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox