On select Fridays, between 11 PM and 3 AM, you will find Teanna Herrera walking up and down Santa Monica Boulevard. She’ll be accompanied by a swarm of volunteers and advocacy workers in black and pink shirts, carrying paper bags and book bags, perhaps even water bottles. They stand out on these streets as they travel en masse, drifting down side streets and sidewalks passing alongside many locals making their way to or from various nightclubs and bars.

“We’re reaching out to the public,” Herrera told INTO. “To the homeless population and the trans women who are out there doing sex work.”

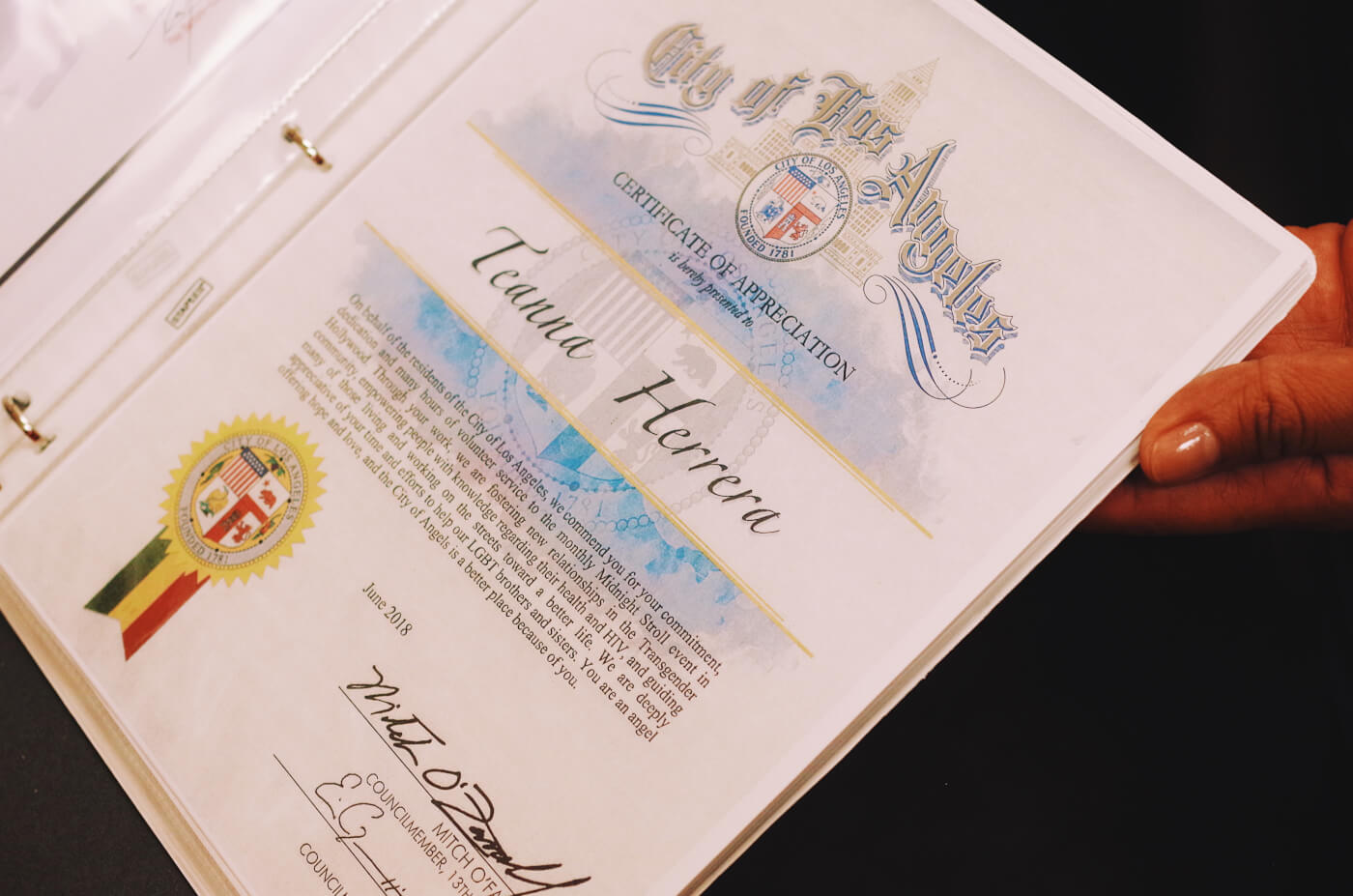

Herrera and others are participating in the Midnight Stroll, a largely volunteer-based program designed to assist displaced LGBTQ persons. Herrera participates in the Stroll through her work as a Victims Advocate at St. John’s Well Child & Family Center’s Transgender Health Program, where she connects queer people – primarily trans women of color and the undocumented – to health care and safety.

“When I’m out there [on the Stroll], reaching out to the public, they know me,” she said. “They come to the clinic. They all know me. They know my life experiences.”

These experiences are the reason she connects so closely to this group: A Los Angeles native, Herrera transitioned in the 1980s at just 17 years old. She’d been doing sex work since 16, joining friends who were already involved.

“The majority of the guys were coming by, picking us up,” Herrera said. “At that age, I didn’t see it as nothing bad … I would do that on the weekends while still maintaining a job, to camouflage in case my parents would ask where I got the money from. On top of that, it escalated to me having sugar daddies.”

“As I got older, I started thinking: ‘Wait a minute – I’m a teenager,’” Herrera continued. “These are like child molesters. It started kicking in.”

This is when things changed for her, she said. She realized she could shift away from sex work and instead turn to one of her many side-jobs, which included a brief stint in cosmetology to working for her sister’s garment manufacturing company to entering a budding computer industry in the late 1990s. However, while jobs came and went, sex work was always there for her. It was validating in some ways and, for many transgender people, this experience isn’t unique.

“I’ve learned to survive on sex work in the past because trans women are not given opportunities for employment,” Herrera said. “We’re all human beings and we should all be entitled to some line of work but, if nobody wants to give us employment or hire us, what do we do? We turn to sex work. It can be dangerous and very stressful.”

“And there’s nothing wrong with sex work,” Herrera continued. “But you have to be well grounded and mentally set because of the people you’ll have to be dealing with, in case they are psychotic or under the influence.”

Herrera has experienced this aspect of the job in many ways. She was the victim of three different hate crimes. She lost several friends to HIV. She was arrested twice for prostitution – and that reset her mind, driving her to become an advocate for persons like herself.

“The most I ever did in county jail was 90 days. Three months and I had enough,” she said. “That’s what made me want to get into corrections because I saw all the bad stuff happening in there. As an inmate, I could see that there was still prostitution going on inside of the correctional facility. I had seen so much.”

Through various programs and classes, by way of institutions like Los Angeles Community College and the Asian Pacific AIDS Intervention Team (APAIT), Herrera reframed her experiences to be an advocate for those in need – and has thrived.

“I advocate by offering the services, reaching out to them, showing them this is where I work,” Herrera said of reaching the trans community. She spends most of her time at St. John’s educating organizations across Los Angeles County on transgender issues, as well as the community’s overlap with human trafficking. Within St. John’s, she runs Seeking Safety, a six-week program for “trans women of color who have been living or experiencing trauma, high risk for HIV and Aids, and drugs and alcohol.” Herrera is also a member of the Transgender Advisory Council, a group of transgender individuals who work with Los Angeles city government and elected officials to tackle issues facing their community.

Rizi Timane, the manager of the Transgender Health Program at St. John’s and founding director of the Happy Transgender Center, sees Herrera as a vital part of his team, and an asset in community outreach.

“Teanna brings a vast knowledge about trans women and trans patients,” Timane said. “She brings that understanding and empathy to her role as a peer leader and victims advocate. [Patients] are more inclined to listen and to trust her advice on how to possibly find a way into mainstream employment as well as how to stay safe while still in the sex work life. … She goes out into the community to present and share her story and attends important community meetings where she advocates for the community as well.”

And this is crucial in health care environments because, as studies have shown again and again, there are so many barriers to getting transgender individuals health care. Advocates like Herrera are crucial, according to Emily Allen Paine, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Texas at Austin who is studying how gender and sexuality are shaping the health of marginalized groups.

“We know that LGBTQ groups access care – both preventive and acute care – less often than their straight peers,” Paine said. “One of the major reasons is they fear discrimination and stigma in those environments.”

In health care settings, trans and gender non-conforming individuals are often misgendered, their identities are assumed, and they are forced into a narrow model of care. Health providers often fail to recognize a person’s identity or embodiment which leads to disruptions in care, stemming from microaggressions and overt harassment and other stigmatizing behaviors.

“What’s really important is that LGBT people feel recognized in health settings,” Paine said. “When someone like Teanna is in a health care position, she’s able to help educate providers on the diversity of experience…She can really relate to the people she’s doing outreach for. That really matters.”

“It’s important to have people in your organization that reflect a population served,” Paine continued. “Even if you can’t go out and hire a bunch of new providers, you can have these community members creating protocols and practices that will affect those populations.”

Jazzmun Crayton – health and policy coordinator at APAIT, creator of the Midnight Stroll, and board member of the Transgender Advisory Council – recognizes this in Herrera and sees her as an asset for this specific reason: in order to help, you need people who can share how they’ve been helped.

“Someone with a lived experience can come from a very beautiful lens because they have nuance and texture and are speaking from past experience,” Crayton said. “She represents the hope that there is a chance for them.”

Herrera’s work is crucial because minority communities must advocate for themselves, and encourage others to advocate, too.

“Having queer people support queer people is a powerful exchange,” Crayton says. “There’s so much giving. There’s a level of understanding no one could possibly understand unless they’ve had that experience…There’s just this deep understanding at the core, like, ‘I know what this feels like. I don’t know what it’s like for you, but I’ve been there. We’re affected by each other.'”

Herrera says she will continue to work, to keep helping people who she sees herself in – but the real work starts with the individual. In her experience, a person has to see that they need help, and they need to make their minds up to make a change before any work can be done.

“I can’t baby them, I can’t be holding their hands,” Herrera said. “I can tell you the resources – and it’s up to you if you want to obtain whatever it is that is out there…You’re a grown person. It’s up to you. If you fall,” she continued, “always remember we are here to help you.”

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox