With a recently published retrospective book of his work, a piece commissioned for the Cannes Film Festival, and several of his portraits hanging from light posts in Chicago, out pop artist and painter Tennessee Loveless hopes to follow in the footsteps of his idol, Keith Haring.

Loveless, a 40-year-old self-proclaimed “visibly gay” man with striking face tattoos, started his career in licensing and production development at Disney. Working behind the scenes for several years, he finally got his break when someone saw his work hanging in his cubical.

“Disney thought I was eccentric, but I could paint, so they went with it,” Loveless tells INTO. “I was never shy about who I was there. I learned at a young age, that as long as you’re a good person, you can be unapologetically you. If people hold you accountable for your queerness, then that’s their problem, not mine.”

Loveless went on to create officially licensed art for both Disney and Warner Brothers, as well as several other brands like MAC, OPI, and Urban Decay, but in 2018, he’ll make history with his Disney-published book that featured 100 silhouettes of Mickey Mouse. The Art of Tennessee Loveless: The Mickey Mouse TEN x TEN x TEN Contemporary Pop Art Series is a pop journey exploring the history of the icon, while bringing global, societal, and personal context to the imagery. With text written by by David A. Bossert, the book explores Loveless’ childhood growing up gay in Georgia and his early struggles in a conservative environment.

“It isn’t just a regular Disney book,” says Loveless, who now lives between Paris and Chicago. “I’m the first openly gay artist with a story Disney has published along with my artwork.”

Another challenge Loveless faced was the diagnosis of severe colorblindness at the age of seven. He can see the colors blue and yellow, but red hardly registers, and green not at allit looks grey and muted.

“My life is a dim room in the color scheme,” he says. “There’s no color value.” But, he explains, he’s able to create his colorful work by labeling his paints with pigment codes.

“If I’m trying to communicate an emotion or something that exists in the world, like a fire for example, I’m going to know what color code that is because I’ve been taught that,” he says.

His aesthetic outside of Disney and other branded work centers on being queer. Loveless came out at 16, in Marietta, Georgia, but after being bullied by classmates, and not feeing supported by family, he escaped to Athens, and was embraced by the drag community there.

“The first people who gave me a reason to paint were drag queens,” Loveless says.

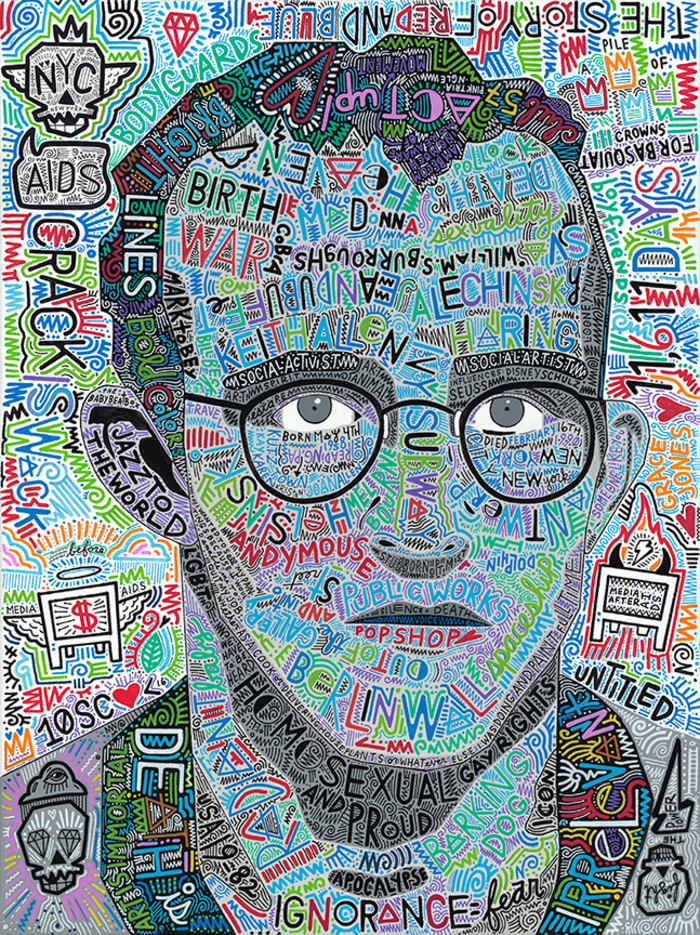

After his lover of 15 years died of a heroin overdose, Loveless painted his first portrait and included the story of their relationship on and around the face. He started doing portraits of more public figures after that, with the intention of illustrating what he feels are their true stories. His first 10 portraits of drag queens were hung along light posts in Chicago’s Boystown neighborhood, and the city’s LGBTQ community center, The Center On Halsted, uses them to highlight their HIV awareness program Get to Zero.

The issue of HIV/AIDS is an important one to Loveless personally. He’s lost several close friends to AIDS, has close friends living with HIV, and is a regular user and advocate of PReP. He recently created a portrait of Elizabeth Taylor in tribute to the actress/activist and the Liz Taylor AIDS Foundation.

His work Art Outsiders is series of portraits of heroes in their fields. People who’ve made a difference, he says. Included are such luminaries as Andy Warhol, Judy Garland, Tesla, and Vincent Van Gogh. He’s also done a portrait of Keith Haring, whom he says is a catalyst for much of his work.

“[I admire] his work during the AIDS era, when Reagan was doing nothing,” Loveless says. “Haring used his voice to raise awareness. We have an option as artists to be incredibly selfish and just do our own aesthetic and voice, but I want to take it further and do what Haring did, use my abilities as a painter to create portraits and pieces that have to do with political justice or queer identity or AIDS awareness.”

Loveless is now focusing on his long-term project Drag Landscapes, a series of in which he anticipates 15 years of work, hoping to create 500 individual international drag queen portraits. He says he wants to capture “their stories growing up queer, and how drag became a part of their lives.” Drag Landscapes will showcase “both the heartache and the power of being queer.”

“I think you’ve got one life to live,” Loveless says. “Why not use your voice for others and not yourself? Today more than ever we need warriors.”

All images courtesy Tennessee Loveless

Don't forget to share:

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox