There is a level of insincerity and intentional distance to The Gospel According To André that feels so boringly contemporary–everything its subject is not. The film, directed by Kate Novack, is, as critics like the New York Times’ Jon Caramanica have pointed out, “frustratingly static” in that makes “a point not to get in its subject’s way.” But in more plainspoken and pointedly 2018 terms, one watches the film and can’t help but think of it is as nothing more than a 94-minute Instagram post of self-aggrandizement. I offer it the same response I give its 90-second long forefathers: “This bitch fronting.”

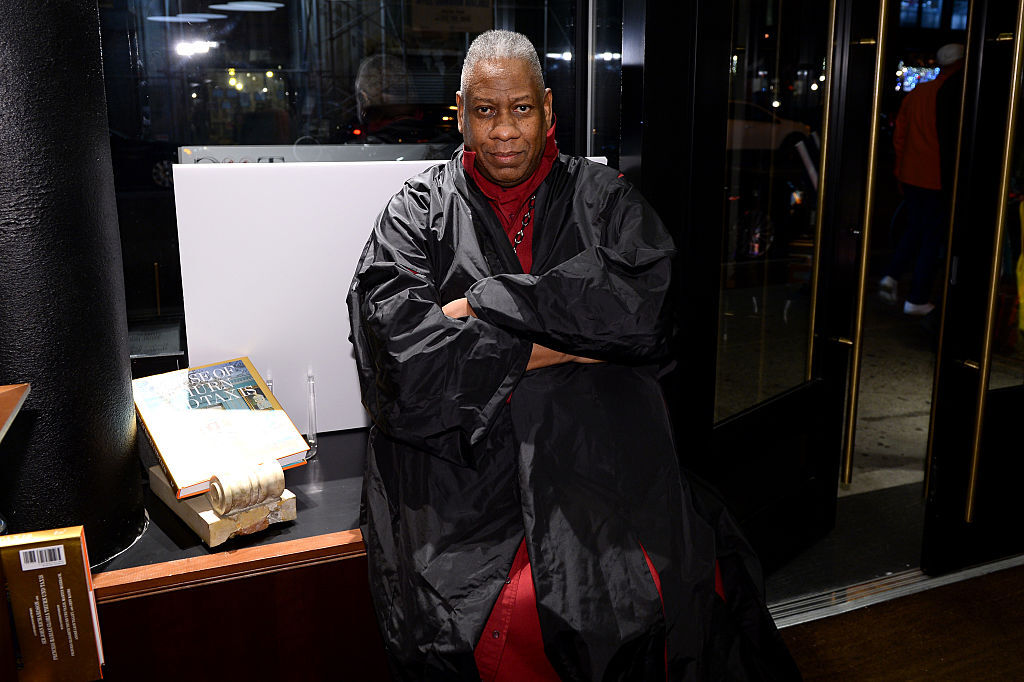

Make no mistake, André Leon Talley, or better yet, the André Leon Talley, has every single right to be self-congratulatory. He is a visionary. He is a trailblazer. He is a force. As a child of the Jim Crow South who grew to be a Black man of towering presence, for him to succeed in the fashion world as he has is unprecedented, and indeed, worthy of a documentary.

However, there are always two ways that a documentary can go: The film can either tell you the truth, or the version of the truth it prefers to present. That’s why I invoked Instagram — we all like to show off the best version of ourselves, but if an opportunity like this presents itself, why not go beneath the veneer?

Why not offer fashion’s equivalent to 2010’s Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work, which peeled away the groundbreaking comedian’s mask and revealed the struggles and sacrifices that coincide with leading a pioneering life. It showed you that even a legend can struggle — particularly as they age— but one couldn’t help coming out of the film feeling motivated, inspired by the beauty of perseverance. Instead, The Gospel According To André is an informational version of his storied life and career.

He offers his musings about what fashion and style mean as a bunch of famous people who don’t seem to really know him lavish him with praise. There are some flickers of those more familiar — notably folks who knew him before he found his way to New York and Paris — but you get the sense they are for nostalgia’s sake.

One of the documentary’s talking heads, Yale Divinity School theology professor Eboni Marshall Turman, offered what should have been the basis of the film: “At once a legend, and he is also a tall, big Black man born in the American south. And as such, there will always be great tension there.”

She went on to add, “How great it is to be André Leon Talley, but he knows what it has taken.”

Part of that for Talley was his decision to pursue a career at the expense of anything else — including a romantic life.

George Malkemus III, a friend of Talley’s who works at Manolo Blahnik, also echoed Turman’s sentiment but went further. “When he was becoming André Leon Talley, a partner mattered less,” he explained. Malkemus went on to add with respect to love: “The ships sometimes pass.”

In 1994, The New Yorker’s Hilton Als profiled the then 46-year-old Talley in a piece called “The Only One.” Referring to Talley’s romantic yearnings as “melancholic” and “immune to involvement,” Als writes: “Generally, he is attracted to men who avoid him. He avoids the potential rejection and hurt that are invariable aspects of romantic love.”

Decades later, Talley lets his guard down most when the subject is broached.

“Listen, I have no love life,” he says in the film. “There is no such thing as a love life. I never had a love life. I was busy doing my career. That is the flaw in my life that is there: I never have fallen in love or experienced love.”

In deciding not to seek love for himself, “I kept loving the world I was in.” But did that world love him back? And was that world not agonizing in its scarcity of people who looked him?

In the recent New York Times profile of Talley, “André Leon Talley’s Next Act,” he says of the industry to which he’s pledged all allegiance, “Fashion does not take care of its people. No one is going to take care of me, except I am going to take care of myself.” It is bewildering as it is befuddling to hear him declare that at nearly 70 years old, “I’m broke.”

And when he said he only been in love twice, including with a woman named Anne Bibby, she responded with laughter and clarification. “We were very good friends,” Bibby explained. “But he was in love with what he was doing.”

It is not my belief that a person needs to have a lengthy history of romantic and sexual experiences in order to convincingly say they’ve led a happy, fulfilled life. Back in 2012, Tim Gunn revealed that he hadn’t had sex in 29 years. Citing a traumatic experience with a past partner, he explained, “Do I feel like less of a person because of it? No.”

While Talley hasn’t answered a similar question, and it is not my place to project such a sentiment to him, he has spoken differently about his lack of intimacy.

On Fresh Air with Terry Gross, Talley said: “I regret to this day [that] I have difficulty responding to physical emotion and it’s based on a childhood experience — I don’t know what it is, I can’t think about that now — but I do regret not having that relationship.”

Yet, he does declare, “I’m not going to say it’s the worst life; it’s been a wonderful life.”

Indeed, Talley’s talents, vision, intelligence, humor, and sparkle are noticeable in The Gospel According To André, but it’s been in the interviews in support of it where he pulls back on the fabulousness of his life because there is more to life than just work. It’s that imbalance that makes Novack’s storytelling lacking. As a Black gay man, I often worry about my own future.

I think about the racism I still have to endure. Then I consider the homophobia that is just as pervasive. I also have my worries about putting too much into work at the expense of my personal life and what that could lead to. And there’s the fact that I have a book out soon that’s largely about me trying to overcome old trauma and not deprive myself of human connection. Because I worry about dying alone and I sometimes question not necessarily whether it’s worth it, but what it will give way to as I get older.

Maybe Talley didn’t want to answer some of those questions because he didn’t have the answer, but I wish his director had tried to pull them out of him. He is a walking Black history and Black queer history monument. He has, as he made clear, led a wonderful life. Still, it’s been a lonely one. Lonely in his professional life, given that while he has helped incorporate more Black models, photographers, and designers in the pages of Vogue, he has no known person that looks and loves like him in those halls as his successor or one of many successors. Lonely in his personal life.

Ultimately, the documentary made me sad. I wrestled with whether that was largely due to my own fears, but either way, it left me with more questions than answers. It also left me terrified.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox