Spoiler alert: Major spoilers ahead for the new 2018 version of Halloween and Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House ahead.

More than any other genre, horror films capture the American national mood. They hold a mirror up to America’s face and cut behind the facade straight to its psyche. In the 1980s, audiences watched as sex-crazed teens embracing the “free love” ethos of the 1970s were hacked and slashed. In the 2000s, fear of biological warfare equalled a rise in zombie contagion films. When you watch a horror movie, you’re not just watching the characters on screen fight for their lives — you’re seeing what makes us as a nation shit our collective pants.

October this year seems to be in overdrive, for some reason: Netflix released a glut of spooky content, people are trying to pop Hocus Pocus virgins’ cherries with renewed vigor and I actually bought materials for a costume for the first time in years. But aside from the onslaught of creepy content, something has stuck out to me: What’s scaring us is the older generation, baby boomers and early Gen X-ers who currently have a vise grip on institutional power and who seem hellbent on driving this country into a ditch. We feel like we’ve inherited a shithole, and in light of news just this week that the Trump administration wants to erase trans people from federal policy, we sometimes feel as helpless as a babysitter whose boyfriend is on his way with a scary video.

October saw the release of the Netflix original series The Haunting of Hill House and David Gordon Green’s film Halloween, both of which center narratives about the terror of intergenerational trauma. Both, in very different narratives, argue that what scared us before we exited our childhoods will continue to mold us as adults, often for the worse. Both films to varying degrees also blame parents or older generations for current predicaments. The children of Hill House won’t let their father off the hook for ignoring their multiple warnings that their summer mansion home was haunted by a menagerie of past homeowners or for the death of their mother.

In Halloween, the franchise’s heroine Laurie Strode (played to perfection once again by Jamie Lee Curtis) is haunted by the franchise’s looming presence, The Shape aka Michael Myers. Halloween is a story ostensibly about trauma and what happens after a person, especially a teenage girl, experiences trauma. It’s hard to watch Laurie Strode and not see someone like Christine Blasey Ford, who bravely aired her own trauma in front of the world at a congressional hearing so that she could tell others of her psychological tormentor, newly sworn-in Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh.

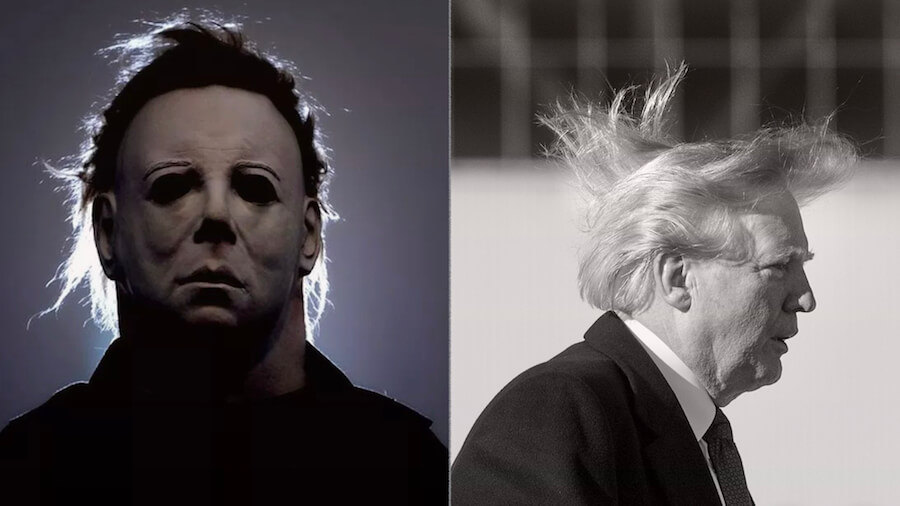

Laurie Strode could be a stand in for Ford or any other woman who has been silenced by her assailant, but on the other end, we have the menacing Michael Myers, a person whose power depends on silencing others. Myers, with his bleach-white mask and terrible fake comb-over hair, does come off a little Trump-like throughout the film. He is relentless in his pursuit of his victims while also never explaining exactly why he chooses to kill who he does. (Also, take a peep at who he kills throughout the film: women, an effeminate young man, a young black kid and two journalists. The only person he spares is a young, presumably innocent white child. How much more MAGA can you get?)

While the film is purportedly about the trauma that women suffer at the hands of other men, the film also reflects a problem in America at large: It is way more interested in the suffering of Michael Myers than it is Laurie Strode. Strode gets relatively few moments on screen alone. She often intrudes into other people’s storylines — the journalists in hunt of a story, her granddaughter’s National Honors Society dinner — while Michael keeps the camera’s focus. Heck, at one point, Myers’ doctor, Dr. Sartain, who’s become obsessed with his subject, literally says that over time he’s shifted from wanting to understand the perspective of the victim to wanting to hear from the victimizer. He’s a “fine people on both sides” kinda guy, it seems.

Now, there are several ways in which Myers and Trump are very much not alike. Myers hasn’t uttered a word since 1978, while Trump’s bloviating never stops. Throughout the film, characters desperate to know why Myers does what he does ask the killer to “SAY SOMETHING!” to no avail. While Trump does have things to say, the urge to hear Myers say something could be read as the way the American people want to know the hidden urges and agendas behind the life-ruining policies of Trump and his whitelash-fueled administration. Why the cruelty? Why the killing? Why the camps? Michael Trump, say something! Myers’ own silence is perhaps read as the way straight white men are not really taught to access their own psyches and speak about the harm that’s been done to them and the harm they’ve exacted on others. (For evidence of this, just watch Kavanaugh’s congressional testimony, an angry slasher film of a verbal harangue.)

People venerate Myers and his actions in a way that seems to mostly let him off the hook, even if Strode does not. When Myers is going to be transferred to a high-security prison, Sartain bemoans that he’ll be treated badly, not too different from conservatives’ “character assassination” reactions to #MeToo accusations against the Roy Moores and Kavanaughs of the world. Several people laugh off Myers as not an actual threat, including the mayor of Haddonfield, who laughs off the fact that a bus with Myers on it was found on the side of the road and that Myers has escaped on Halloween night.

“What are we gonna do, cancel halloween?” Hey, traditions must go on, right?

Speaking of the upturned bus, I haven’t even mentioned the scene that many queer people have pointed to on social media as the film’s lone queer moment. In the scene, a father drives his son out to go hunting — America’s pastime! — and the father slightly chastises his son for loving dance class more than hunting. Though the child is never called queer, he’s certainly written as gentle and, to many people, coded as queer. The father and son, besides being on opposite ends of the masculinity spectrum, also have a huge age chasm. The father looks to be closer to a grandfather-like age. Sure, they both get slaughtered, but the father’s death is offscreen, while the effeminate child gets slaughtered for audiences to see.

In the film’s final act, we get to see Strode evolve from the original franchise installment’s “final girl” to a wise, ass-kicking crone. (Though Halloween: H20 doesn’t exist in this film’s universe, that’s definitely the midway “mother” archetype of the three, given it did take place 20 years before the original and before this current installment.) Myers, the hunter, becomes the hunted and Strode is able, seemingly, to take back the power — even if the film, in classic slasher style, does leave Myers’ death open to interpretation.

In a way, Strode’s performance in the final act is like our own quest to breathe in this oppressive patriarchal environment. It’s part gritty survivalist mechanical victory and part wish fulfillment. Many marginalized people will never get the chance to lock their demon in their basement and light him on fire. But they can do the work of facing their trauma every day and, eventually, moving on. The next generation, represented here by Strode’s granddaughter, will one day get to wield power.

Halloween, then, has a message for those of us who are tired of living under heteropatriarchy: We’re the final girls. (It’s a message that the film implies but isn’t really able to pull off all that well, but I’m giving it the benefit of the doubt here.) If we prepare and change the systems around us so that law enforcement, government, media and other structures in place can keep these white men accountable, we will have our victory. With a better hold on how to deal with this trauma, the next generation will brandish the knife.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox