We are currently swimming in a sea of queer film & TV. Just this past year, we have seen LGBTQ characters at the center of runaway hits (Netflix’s Queer Eye reboot), critically-acclaimed awards darlings (Angels in America, Call Me By Your Name), and even big-budget studio films (Love, Simon). Queerness has become mainstream. But despite this wealth of gay programming, there are very few queer stories on television quite like Killing Eve.

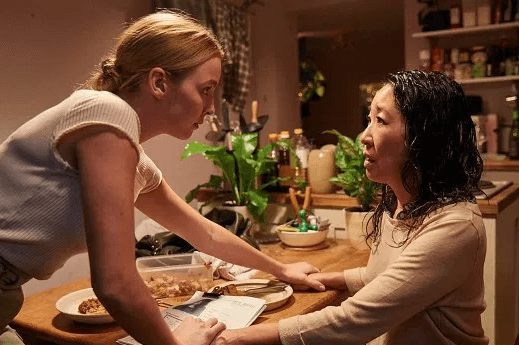

The new BBC show, which was (deservedly) showered with nominations from the Television Critics Association last week, tells the story of a British cop, Eve (Sandra Oh), as she hunts down an assassin named Villanelle (Jodie Comer). Eve and Villanelle become fascinated with each other immediately, long before they ever meet face-to-face. Unlike other LGBTQ stories that construct narratives around a centrally defined relationship or identity, Killing Eve never explicitly names Eve and Villanelle’s desire. It is often sexual, at times romantic, and occasionally vengeful. No matter what way I try to spin it, I can’t quite seem to find the words to pin it down. Some writers have imagined how the show could be more explicit about this central relationship, but what I find most exciting about this relationship is how it resists simple categorization.

When gay characters are depicted in media, their queerness is too often forced into a restrictive template. We usually only see characters that are out and proud, and if they are not, they must learn to become out and proud. Other shows may drop hints of a character’s homosexuality without it leading anywhere, a practice referred to as queerbaiting (I’m looking at you, Sherlock). Due to television’s long history of queerbaiting and the “bury your gay” trope, many critics understandably demand that characters’ queer sexualities be explicitly named. However, while creating gay role models is essential, the problem here is that the expectation for one’s sexuality to be clearly defined becomes just that: an expectation for stories to fit within a narrow understanding of what it means to be gay. This expectation seeps into our celebrity culture, too; it demands that actors either publicly come out in a way that feels familiar or be vilified — which happened recently with Lee Pace — without recognizing that each person’s process can be completely different. We unfairly separate queer narratives into those that are “legitimate” and “illegitimate” based on mainstream conceptions of gayness.

In a recent episode of the Still Processing podcast, hosts Wesley Morris and Jenna Wortham wrestle with these questions. They make excellent points about Hollywood’s commodification and straightening of queerness, but they also criticize Janelle Monae for coming out as pansexual in a way that feels—perhaps unintentionally—like a ranking of acceptable identities. Throughout their conversation, they place great value on individuals who make unambiguous announcements about their sexuality. But while there can, of course, be something quite powerful and liberating about coming out in such a conclusive way, the narrative of the closet does not hold true for everyone, nor should it have to. When discussing the musician Rita Ora, Morris explains that people wanted a “cleaner declaration” of her sexuality, but what if some people’s queerness simply isn’t clean?

This void of messy queer narratives is precisely why the ambiguity of Killing Eve is so thrilling. It depicts a queerness that we do not already have a mold for in media; it is not a joyful love story, a tragedy, or a tease. It never outright explains its characters’ sexualities, but unlike shows that queerbait their audiences, Killing Eve does not need to name the relationship between Eve and Villanelle in order to recognize it. Both characters’ interest in the other is rooted in a desire of an unknown — a life away from the men that presently structure their lives. From the get-go, Eve is shown to have a nice job with a loving partner, but something is clearly missing; she grows bored and impatient with her surroundings. Villanelle, too, finds something refreshingly new about her playful cat-and-mouse game with Eve. She has no qualms about disposing of her father-figure handler Konstantin or the assorted men and women she encounters during her travels, but she can’t seem to shake Eve — nor does she want to. Eve and Villanelle are both deeply affected by each other in a way that is not only sexual or romantic, but also rooted in the potential of an alternate lifestyle. They enter into an elaborate dance, edging closer to one other while always being just slightly out of reach.

The archetype of the killer and obsessed cop is nothing new. It has recurred over decades, perhaps most notably in Silence of the Lambs and most recently in Netflix’s Mindhunter. But what makes Killing Eve remarkable is how it treats Eve’s desire. While tracking Villanelle, Eve does not fall into a downward spiral and is not forced to grapple with some “inner darkness.” Unlike the cops that have come before her, Eve is fiercely competent. She never loses sight of the fact that Villanelle is dangerous, and when Eve almost lets her guard down in the finale, she still stabs Villanelle in the chest.

And despite this very real danger, series creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge paints their relationship in light flirtatious brushstrokes. Eve throws her job and respect for authority out the window in favor of finding Villanelle, a decision that isn’t portrayed as naïve but rather as invigorating. I couldn’t stop myself from addictively watching episode after episode to see how these two women’s lives would continue to intersect. The delightful chaos of the show stems from its queer sense of play, from the thrill of Eve and Villanelle discovering something about themselves within the other. Eve’s obsession with Villanelle is not a mistake. It opens up doors—it is an entry-point into a new life. In the finale, their connection comes to a head when Eve surprises herself by trashing Villanelle’s apartment. She pretends she is in Villanelle’s mind to explore how it feels and how it changes her. And in this moment, I found myself letting out a sigh of relief. Finally, I thought. Eve’s queerness is exhilarating because she is flirting not only with another person but also with a version of herself that she sees reflected through Villanelle. And it is an image of herself that she doesn’t necessarily hate.

It is clear that Eve and Villanelle will never have a monogamous or loving relationship, but it is also clear that there is a sexual nature to the games they play (Villanelle tells Eve, “I masturbate to you”). The show does not shy away from its characters’ sexual attraction but also complicates this narrative at every turn. Killing Eve reflects an amorphous view of queerness — a queer sensibility rather than a queer identity. A sense of play, curiosity, and unfiltered desire. It is a different, but equally important, form of representation. And, as of the end of its first season, this delightfully bizarre cat-and-mouse game has no ending in sight.

Killing Eve’s queerness isn’t a clean declaration — it is a feeling, a taste that permeates across the screen. Seeing loving monogamous gay couples in TV and film can be important for many people, but there is also something freeing about a queerness that does not need to, and perhaps cannot be, named. Killing Eve relishes in its winsome ambiguity, forcing us to ask: why do we demand our queer stories be so cut and dry? What is our stake in explicitly naming and identifying a particular form of queerness — one that so often resembles hetero relationships? And whose stories, like Eve and Villanelle’s, do we risk leaving behind in the process?

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox