London’s queer spaces have been closing at an alarming rate over the past decade. Rising rents, gentrification, and a raft of redevelopment initiatives are causing many LGBTQ venues to close down, leaving entire neighborhoods without safe havens for queer people. According to a report by University College London (UCL), the number of LGBTQ venues in London has fallen by 58% from 125 in 2006 to 53 in 2017.

Iconic spaces in the city, including cabaret and burlesque nightclub Madame Jojo’s, lesbian venue Candy Bar, and gay pub The Black Cap, have closed over the past decade. When it was announced that the legendary gay pub and club The Joiners Arms was set to close in early 2015, regulars and friends of the East London institution started to mobilize against the proposed shutdown.

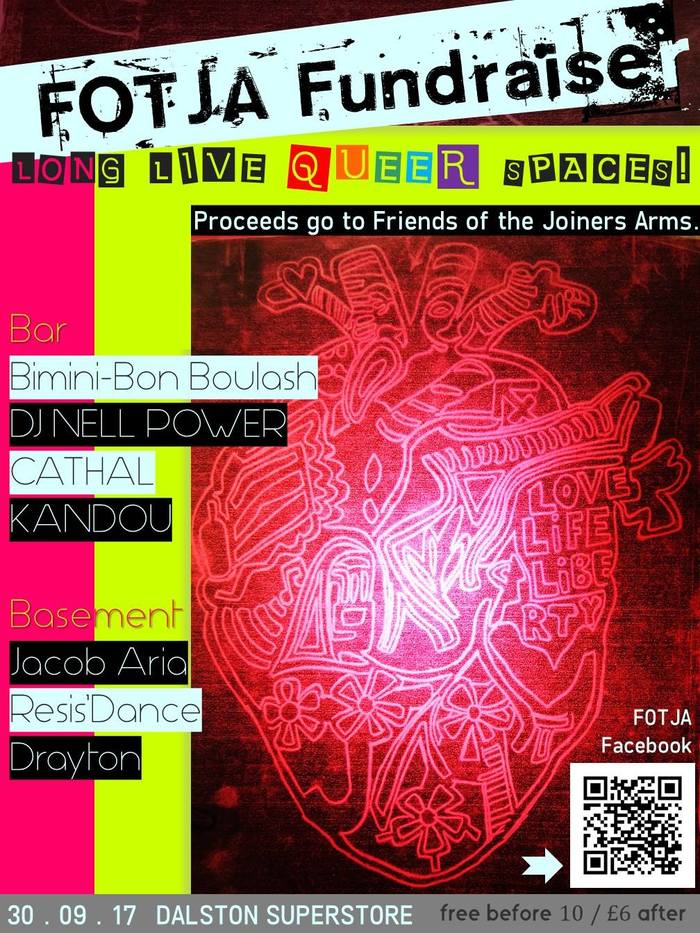

“The Friends of The Joiners Arms (FoTJA) formed when a group of people; patrons and friends of The Joiners Arms rejected the idea of losing a community space they felt belonged to them,” says Dwayne Clarke, a campaigner with Friends of The Joiners Arms. “United in opposition, the primary objective was to prevent the bar/club from closing down.”

The FoTJA group has been organizing demonstrations fighting for the reopening of The Joiners Arms for more than three years since developer Regal Homes bought the venue in 2014 and announced plans to turn the plot into luxury flats and office space. Thanks to the perseverance and dedication of activists, not only has the local council made it a condition of the redevelopment that an LGBTQ bar must be incorporated into the premises, but planners have also said the new queer venue will have a lease of at least 25 years, not pay rent for the first year, and receive £130,000 towards fit-out costs.

This agreement is believed to be the first time in the UK that the sexual orientation of a venue’s patrons has been a key condition for gaining planning approval, with the storied club still being relevant more than 20 years after it first opened its doors to the public in 1997. Dwayne believes that it’s difficult to measure the impact The Joiners Arms has had on the LGBTQ community because it has come to mean so many different things to a diverse range of patrons.

“To some, it was an iconic institution with a history and legacy too important to lose. To others, it was a safe place to hang out and unwind with your mates. Perhaps those two things, that ability to be both at the same time, was probably the really special and ultimately unique thing about it,” says Clarke.

Although extremely strong legal protections exist for LGBTQ people in the UK, the importance of LGBTQ-inclusive spaces remains paramount at a time when anti-gay hate crimes are on the rise. According to the charity Stonewall, hate crimes against LGBTQ people shot up by almost 80 percent over the past four years with 40 percent of trans individuals experiencing a hate crime directly due to their gender identity.

Doctoral researcher Laura Marshall, who worked with Dr. Ben Campkin on the UCL report on LGBTQ venues, points out that the vast majority of LGBTQ spaces in London are operated by predominantly white, cis, gay, middle-class men, meaning diverse spaces are uniquely precious in this environment.

“LGBTQ clubs run by and for women, trans and non-binary folks, and people of color are highly valuable to members of these communities. These clubs actively redress unequal access to space and intersecting oppressions commonly experienced elsewhere (including mainstream LGBTQ spaces) such as misogyny, femmephobia, transphobia, racism, and homophobia. Recognizing these asymmetrical power relations within LGBTQ communities is essential,” Marshall tells INTO.

There are many complex reasons behind the unprecedented decline of queer venues, from serious incidents of crime leading to licenses being revoked to one-off railway projects like Crossrail seeing historic venues bulldozed down. But by far the most significant factor in the closure of these spaces is landlords wanting to capitalize on skyrocketing property prices in the capital and deciding to develop the previously commercial spaces into private flats and luxury apartments.

Redevelopment projects have been directly responsible for the closure of 57 of London’s queer venues since 2006 with a further ten closing due to often disproportionate rent increases or lease expirations. It’s not just LGBTQ pubs and clubs that are shutting down across the UK, but the venues catering specifically to queer people are closing at a faster rate. According to the UCL report, 25 percent of London pubs closed their doors from 2001 to 2016 and there was a 44 percent fall in the number of nightclubs operating from 2005 to 2015.

The growing awareness and interest in the loss of spaces for London’s LGBTQ community has led to politicians taking action, with London’s first Night Czar, Amy Lamé, who was appointed by the Mayor of London to promote the capital’s night-time economy, advocating for at-risk LGBTQ venues. Lamé introduced the Mayor’s ‘LGBT+ Venue Charter’, a five-point pledge that venues can sign to show their support to the LGBTQ community, and the Mayor later funded the £10,000 UCL report to better understand the factors contributing to the closure of these safe spaces.

A handful of new venues are opening up around the city. East London queer pub The Glory has become a drag hotspot since opening in 2016, late-night club South Bloc in Vauxhall launched last year and a 750-capacity gay club is set to open its doors later this year. Other groups fighting against the closure of vital LGBTQ venues, including the Black Cap Foundation and The Royal Vauxhall Tavern Future campaign, are challenging the unrepentant closures of LGBTQ bars and clubs.

“These campaigns have each achieved successes in different ways and the passion and commitment shown by members of these groups is a testament to the value of these venues. That said, protecting LGBTQ spaces should not require this level of labor from LGBTQ communities. Keeping London’s LGBTQ venues open relies heavily on borough councils since property-led redevelopment often poses the greatest threat,” says Marshall.

Yet, 19 of London’s 32 boroughs now don’t have a single LGBTQ venue and there are no clear signs the trend of LGBTQ bars closing down is set to reverse. While FoTJA weren’t able to prevent their bar from closing, they were instrumental in winning protections for a new LGBTQ late license bar in the future development, with Clarke saying the group ‘hopes to win the lease for this space, and open London’s first community-run LGBTQI+ pub!”

The LGBTQ community in London and elsewhere in the country has evolved massively since the advent of dating and ‘hook up’ apps that have made it easier than ever before to meet other LGBTQ people. Grindr, Hornet, Tinder, and Chappy, alongside increasing social acceptance, play a major role in how many in the community use queer spaces.

“Where there was once a need for such establishments, based on the desire to meet fellow individuals in a safe and inclusive environment, progression in the social realm has begun to erode this need. We certainly are not there yet, but I feel that with a fully inclusive society, such places will become a thing of the past,” concludes Clarke.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox