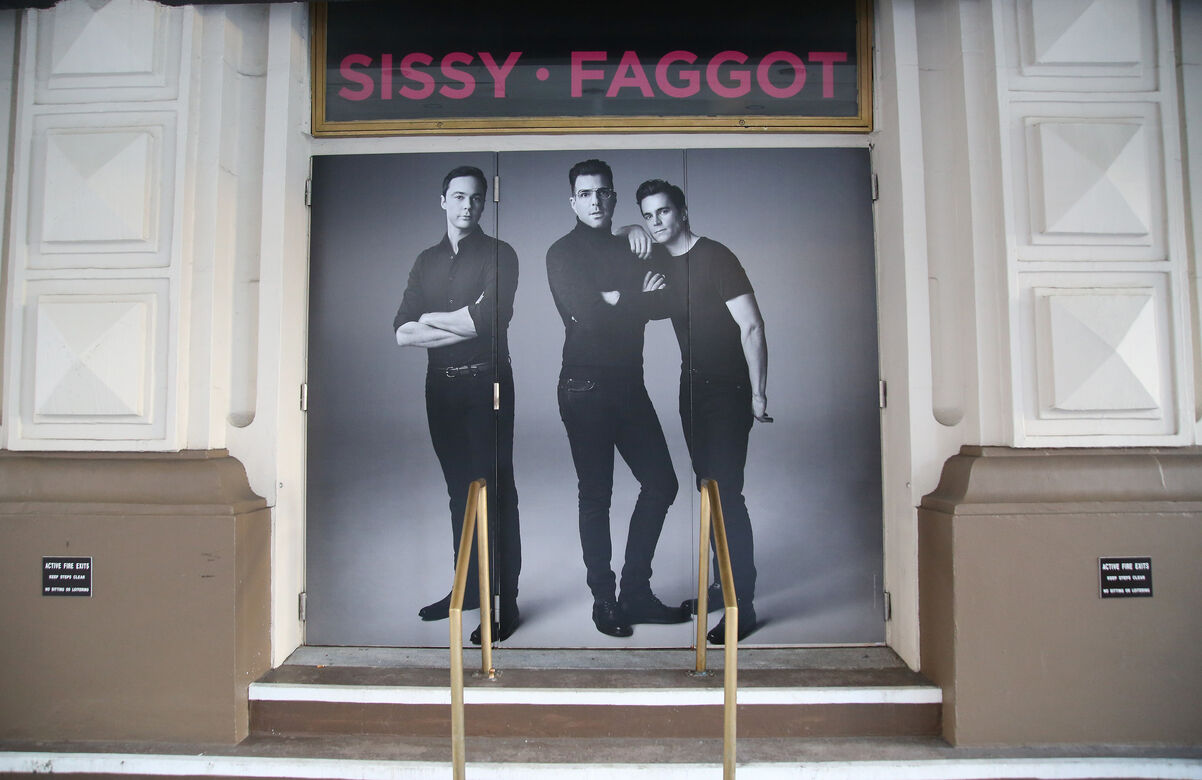

Gay shame is a bit loud– deafening, perhaps. And if it has been a long time since you’ve seen the film adaptation of The Boys in the Band, directed by William Friedkin and based on the play by Mart Crowley – or you’re seeing the Broadway production produced by Ryan Murphy, directed by Joe Mantello, and starring a cluster of conventionally attractive gay thespians in black turtleneck sweaters (just kidding!) – you may have forgotten just how loud it is.

Characters scream at one another, arms flailing, their libations almost lost to the wind. That the landmark play, first staged off-Broadway in 1968, just before the Stonewall Riots (the film adaptation arrived in 1970), could have once been described as “explosive” is not without reason: the dramaconcerning eight (maybe nine?) gay men ensconced in a nice apartment followed the grand theatrical tradition of getting a bunch bourgeois (mostly) white people in a room (in this case, for the sake of a birthday party), only to have the airs of respectability and functionality fall apart, fueled by booze and — certainly a focal point for this gay play, and maybe gay and queer art in general — self-loathing.

The characters, imbibing liberally, pay little mind to the short fuse they’ve lit, and as lasagnas fall victim to the events, each of the characters is left unresolved, still negotiating their relationships to gay shame.

In this journalism economy, the factthat Crowley’s play is being restaged for its fiftieth anniversary requires “hot takes” and personal essays about what The Boys in the Band has to say about gay shame in 2018, and how The Boys in the Band is insular or problematic or dated or a time capsule. And all those critiques are probably valid. But what of gay shame in art more broadly?

Divorced from its incendiary debut and historical context, its pointedly mechanical qualities and dramaturgical derivativeness look more obvious, the style owing a great deal to playwrights like Edward Albeeand Tennessee Williams. The play is laced with homophobic (and misogynistic) language, both part of the gay lexicon as well as indicative of the characters’ psychological and emotional turmoil: “Believe it or not, there was a time when I didn’t go announcing I was a faggot.”

There are, by characters’ own accounts, screaming fairies and Marys and a melange of mimeograph terms for queers that operated in triplicate: a middle finger to Stanley Kauffmann’s 1966 essay “Homosexual Drama and Its Disguises,” which suggested that gay playwrights like Albee and Williams stick to writing about their own people; an ironic yet accurate way of watching gay men linguistically navigate personal/sexual/romantic relationships; and a stinging reminder of what subtext exists within language in itself. These are men mostly in their 30s, who thus grew up in the ‘40s and ‘50s and ‘60s, whose relationship to shame and self-loathing would almost be congenital, not least of all for the one nonwhite character.

Undoubtedly, a staging of The Boys in the Band in a post-marriage equality and post-Trump sociopolitical climate places it in somewhat of a bind: it will reflexively exist as a testament to How Far “We’ve” Come (the “We” being select) and How Far We Need to Go. But that latter part still is prone to being written off as a thing, a feeling of the past. What do you do with it now?

It’s taken far too long to get serviceable and hyper mass marketed fare like Love, Simon, and for every Call Me By Your Name that’s supposed to break through to the mainstream, there’s a highly acclaimed, still fairly accessible queer film which is either praised or written off as dealing with shame and self-loathing. Neither of the aforementioned films even explicitly avoid the subject, but rather tuck it into their plot machinations in different ways.

The promise of a queer (or gay) Utopia seems out of reach, post-marriage equality ruling in the United States, which did a little and a lot to treat a kind of “gay loneliness.”

Does that mean that Utopia should exist in our art? Ty Mitchell addresses the Utopic inferences of Call Me By Your Name, writing, “It calls upon the tragic youthful yearning that is essential to ‘the queer experience’ and offers a comforting revision of events, one in which we get the love we wanted, even if just for a few paradisal weeks. It offers us a kind of utopia a utopia of love. It is, however, an unimaginative utopia, because it can only conceptualize fulfillment of same-sex desire by situating it in a social and historical vacuum, a world without identities, without rejection, and without disease. It is a world in which culture, history, or community could not possibly salvage queer desire as worthwhile, only love and its complete reciprocation. It is a love-utopia wherein not only are sexual identities irrelevant, but even personal identities are interchangeable.”

There is also the arguably more radical Shortbus by John Cameron Mitchell, but he, too, knows well enough the ways in which queer shame shapes identities. The two have radically different approaches though: Call Me By Your Name, though it takes place in the 1980s, is content, like Love, Simon, with a tacitly assimilatory aesthetic; it’s palatable and disinclined to shake the boat. Simon’s desire is explicitly to be “normal.” Shortbus is is happy to be radical and sexy and queer. Does striving for a queer art without shame, in any context or approach, mean looking for an impossible normality, an assimilation into normativity?

Books have been written about the queerness of shame and of queer shame, from Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation to J. Jack Halberstam’s The Queer Art of Failure. There’s Alan Downs’ widely read The Velvet Rage, and Beyond Shame: Reclaiming the Abandoned History of Radical Gay Sexuality by Patrick Moore, and a collection of essays called Gay Shame, edited by David Halperin and Valerie Traub.

Gay shame’s insidiousness can be found in things as innocuous as various definitions and conceptualizations of camp and camp aesthetics, as tender as readings of Frankenstein’s Monster(Charlie Fox writes in the Times, “When you’re gay and grow up feeling like a hideous misfit, fully conscious that some believe your desires to be wicked and want to kill you for them, identifying with the Monster is hardly a stretch”), other monstrous allegories like Closet Monster Cruising, in the painful strains of Rufus Wainwright’s music (in “Going to a Town,” he sings, “I’m gonna make it up for all of the nursery rhymes”), and as the primary target in New Queer Cinema offerings from the 1990s, like Todd Haynes’ aptly titled Poison and Gregg Araki’s The Living End.

Gay shame is not just garden-variety self-hatred, but the knowledge that one belongs to a group, a “collective of outcasts.” “The power of insult and stigmatization is so great that it brings an individual to the point of doing almost anything to avoid being included in the group being designated an constituted by insult,” writes Didier Eribon in Insult and the Making of the Gay Self. Gay shame is slicker than oil, and it sticks to you no matter how desperately you try to wipe it away. What else could fuel a desperation for “masc-ness,” for homonormativity other than to not be tainted with the same oil? What of a vow that may predicate its eradication of shame on assimilation?

If even lauded films like MoonlightandBrokeback Mountain can catch flack for confronting gay shame, there will always films on the margins like BPM (Beats Per Minute), The Wound, and Thelma that not only confront and reconcile with gay shame, but interrogate what its implications and consequences are. The backhanded answer to why a lot of LGBTQ people would rather see something like Love, Simon over BPM, or even Paris 05:59: Theo and Hugo (I mean, besides the subtitles) is that they’re “depressing,” that a movie like Beach Rats is homophobic in miring itself in its protagonist’s yearnings and shame. That they want to see “positive representations.” What’s a positive representation?

This isn’t an attack on films of Simon’s ilk, but a genuine question. In a society that not only still others queerness, but politicizes it, what does “positive” mean? Sexless? (Philadelphia.) Sunny? (Alex Strangelove.) When writers, critics, and audiences plead for honest and authentic queer representation, what does that mean? And what does that mean when shame isn’t at least acknowledged? Certainly, people may be fortunate enough to grow up and live in communities that encourage and support them.

Shame is by no means merely the province of cis white gay men, nor is it only their territory in film: films and plays as early as The Children’s Hour (play 1933, film 1961) and The Killing of Sister George (play 1965, film 1968) confronted lesbian shame and alcoholism, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1978 film In a Year of 13 Moons dealt with the ambivalences of a trans woman, Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (1993) studied the effects of gay shame within the context of Peking Opera and the changing political landscape of China, and Dee Rees’ breakout 2011 film Pariah examined black lesbian shame.

It would not necessarily be inaccurate to say that the austere, the melodramatic, and the emotional tends to have a particular effect on the history of an art form, not least of all with film, and not least of all with queer film. And, though some may protest at depictions of gay and queer shame in art and film, maybe some audiences must confront our a sadomasochistic relationship with seeing it represented at all.

For every studio head that lets us down with a pact broken that someone queer will actually be in a Star Wars or comic book movie, there are other things. The ironic thing about trauma is that the fact that it shapes you and your identity gives it an almost comfortable familiarity. Is the mundanely ideal(Looking,Love is Strange,Paris 05:59:Théo and Hugo) watchable anyways? Why does the audience that allegedly clamors for those stories rarely show up to them? The suffering of women and queers garners accolades; it becomes a self-perpetuating myth.

For gay shame, a Chinese finger trap: if you continue to depict it in art, jagged or sleek, you are perpetuating that shame. If you ignore it, discard it, dust it beneath a kitschy rug, then you erase the experience. There’s no good answer, and no right one either.

Can you remember when you first felt it? As slight as a sliver or as consuming as a spider’s web? I procrastinated on coming out as queer because i didn’t want to give my adolescent peers the satisfaction of being right. Even though I had the privilege of a liberal upbringing, shame still clasped at my senses. But I’d never want to pretend what I felt never existed.

In The Boys in the Band, Harold, looking at the ruins of his friends, particularly the self-destructive party hoster Michael, says with a mix of sympathy, disgust, and genuine curiosity, “Who is she? Who was she? Who does she hope to be?” Asking about past and present trauma and identity, and how that’s skewed and contorted our conceptions of our own futures, he gazes over the din, and over us.

The question hovers over recent theatre works like Joshua Harmon’s Significant Other, whose protagonist has not yet figured out how to situate his gay self in a modern gay world that, too, wants to distance itself from that historical baggage. And it’s in revivals of Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song and Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. And Jesse Green’s essay “A Brief History of Gay Theater, in Three Acts” suggests, more room is being made for other people in the LGBTQ community to tell their stories, to “hijack a canon” as he says it. What will they do with shame? (Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance, running in London, and Taylor Mac’s performances like A 24-Decade History of Popular Music ruefully deconstruct the intersection of gay shame, memory, temporality, and popular culture.) But you know what else is in almost all of these works? Strength. Resilience. A bit of power, too.

Shame is pervasive, arguably culturally inherited. It is persistent. It crawls beneath the skin, parasitic. But however nasty gay shame might be, even destructive, I don’t think the answer is to suggest it doesn’t exist at all. It’s shaped our history, and our bodies. Instead, maybe ask the art to challenge the society that breeds it and perpetuates it in the first place.

Image via Getty

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox