For much of 2020, mobile hookup apps such as Grindr and Scruff were all that remained of my gay social life. Familiar faces and headless torsos vanished from the “nearby” grids, as many with remote-work options fled the city. I spotted the photo of someone from my building among the little squares covering the phone screen and messaged him to ask how he was faring. He never responded – which didn’t surprise me, since he had never acknowledged my “hello” whenever we shared an elevator. Maybe I read too much into it, but I wondered what had happened to our community.

My journey as a gay man began without a roadmap, years before the internet existed. I never faced any overt racism while attending high school in early 1990s Victoria, British Columbia, but a classmate definitely made derogatory remarks during an art class toward gays cruising at a local park. Thanks to him, I learned where I could find my ilk. No thanks to him, I also internalized how this was shameful and must be pursued in secret. After a movie one night, when I wasn’t expected home until past curfew, I mustered up the courage to walk to the park. I shivered the whole way – from a mix of the night chill, nervousness and excitement. Underneath a starry open sky, half a dozen men stood in silence, hands in pockets, by the bushes in the dark. I evaded their glances as I tried to decide if this was truly where I belonged. What I needed was some direction and some assurance everything was going to be OK.

I wondered what had happened to our community.

After graduation, I started calling the crisis hotline for Vancouver’s LGBT center from a payphone and asking volunteers on the other end what were my options – aside from swallowing an entire bottle of sleeping pills – if my parents were to disown me. They encouraged me to come to their support group, and I did. But I was too young to follow them to the bars afterward, so I never really got to know anyone well.

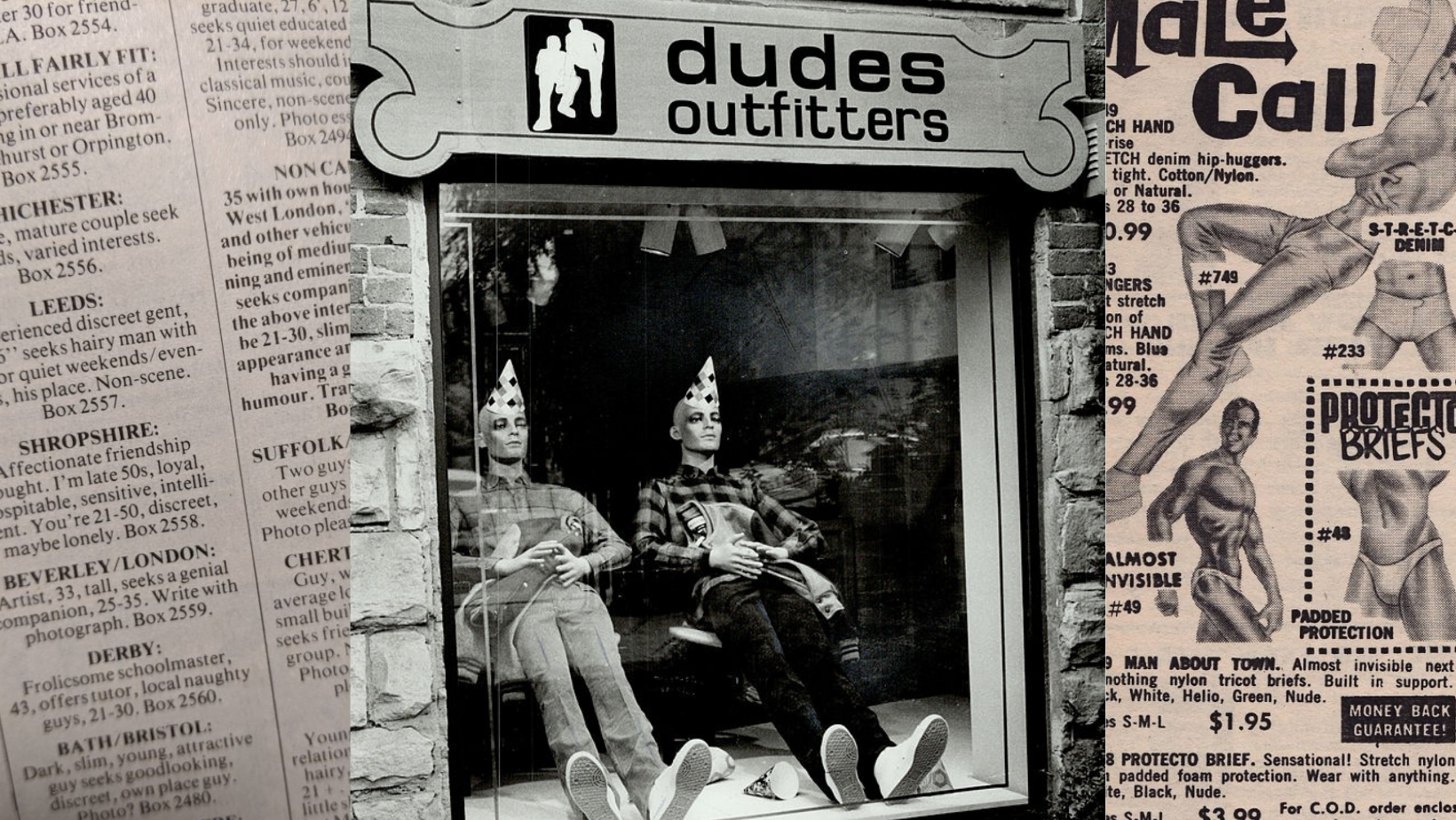

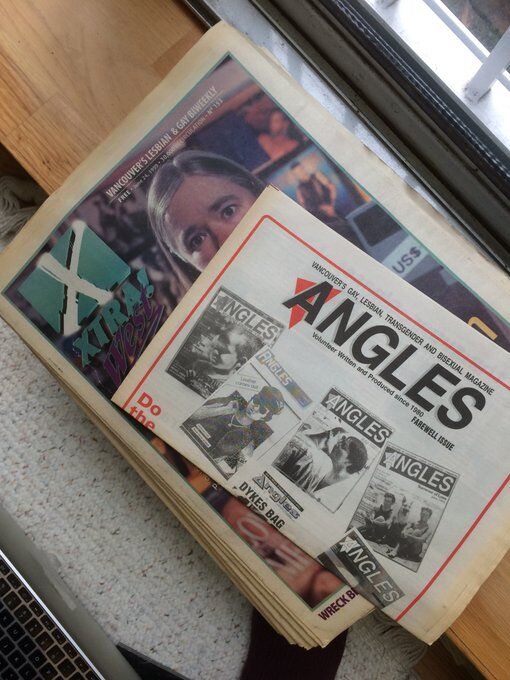

I discovered personal ads in the back of free alternative weekly newspapers. One placed by someone from Seattle offered to put up visitors. I must have been really naïve to buy a bus ticket without contacting him first, but I couldn’t have called long-distance from a payphone anyway. So imagine his surprise when I phoned him upon arriving in Seattle. He instructed me to come to a party the next day, where he would connect me with another man who would host me and a gay couple from Hungary. As for the evening of my arrival, he suggested I go to a bathhouse. Even though I was underage, the attendant realized I had nowhere else to turn and reluctantly gave me a room for the night. My blind faith in humanity was validated, even if not as planned.

Spending a gap year in Montreal, I was fully immersed in the gay scene, participating in LGBT groups and volunteering for the Image+Nation Film Festival. My housemate, whom I met through the school’s housing service, was gay; so was our next-door neighbor. Once the neighbor tried to pass down a first edition “The Joy of Gay Sex” to me. He didn’t understand English, so he thought an Anglophone like me would appreciate it. I was aghast to discover there were no mentions of safer sex protocols and promptly returned it. He had HIV, and this was long before PCPs routinely prescribed PrEP.

Once the neighbor tried to pass down a first edition “The Joy of Gay Sex” to me. He didn’t understand English, so he thought an Anglophone like me would appreciate it.

During my freshman year in Bloomington, Indiana, members of the campus LGBT group introduced me to gay chatrooms on AOL, like Internet Relay Chat and Gay.com. Although people did use those to cruise for sex, there were also general discussions of broader topics from entertainment to politics. There was a sense of community, and after a while, I got to know and become friends with people even if there was no physical attraction. Someone I chatted with on AOL offered to let me stay when I visited New York City for a job interview.

I did not have sex with my host in New York, just as I had not with my host in Seattle. It was as if people were willing to lend a hand simply because we belonged to the same tribe. I would not forget my New York host escorting me to Film Forum so I wouldn’t be late for a screening, and spotting me cab fare to the airport because I had splurged at Tower Records. This kind of generosity would be all but unthinkable decades later amid broader LGBT acceptance.

As high-speed internet supplanted AOL, people fled chatrooms for location-based collage websites like Manhunt and Adam4Adam – precursors to today’s mobile apps. Suddenly, I was shunned by many I might have chatted up, presumably because I was Asian and did not meet their “preference” – perhaps the same reason I was never invited to Fire Island Pines or Provincetown. Etiquette was seemingly gone, and along with it compassion and solidarity.

Not that everything was rosy back in the day. We were, after all, at the mercy of strangers. Though there was kindness, we were also taken advantage of, attacked, robbed, raped and stealthed. Things didn’t improve on that score. I was assaulted twice by gay men in the age of smartphones, one of whom I had met through the Growlr app. It’s just that there is no more of that kindness for the fellow gay like when there were seemingly fewer of us but with a greater sense of common bond.

Every time I scrolled through hundreds of photos on the mobile apps without a “hi” or “hello,” I felt more alone. With The Center and the bars closed during the pandemic, it became painfully apparent we were all yearning for connections yet we were all complicit in depriving each other of those connections by design of the apps and by our own prejudices.

I’ve kept men I’ve met through the years in my contacts and have tried to look them up periodically. Many are married, to either men or women, and do not wish to be found again. Some have died young, much to my surprise. My contacts’ obituaries have been vague, but through mutual acquaintances, I have learned the causes: cancer, diabetes etc. – none of AIDS as far as I know. Nevertheless, I feel like a character in those 1990s gay movies mourning all these losses. I wonder if mine will be the last generation of gay men to feel this way, to have fully experienced community and witnessed its dissolution. Whatever wisdom we have accumulated from our struggles isn’t really useful to anyone – just like I didn’t think that first edition “The Joy of Gay Sex” was of use to me. We have outlived AOL, IRC and Gay.com. I wonder if that rite of passage is passé.

Here’s to the last of us.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox