Even in an age when sharing mundane details online is standard, it’s easier than ever to hide the messier aspects of our lives and control the way others see usuntil, as people often say on social media, someone’s been “exposed.”

Welcome to Exposed, a monthly column where author and activist Chris Stedman invites you to get a little more vulnerable.

Chris is the author of Faitheist and his essays and columns have appeared in Salon, The Guardian, CNN, MSNBC, The Advocate, The Rumpus, and The Washington Post. According to Wikipedia he is “a devout twitter user, fan of Britney Spears and Ciara, and maintains an active gay twitter following.” After spending the better part of his 20s working at Harvard and Yale he now lives in Minnesota, where he is working as a community organizer, writing a book on messiness and vulnerability, and messily tweeting at @ChrisDStedman.

____

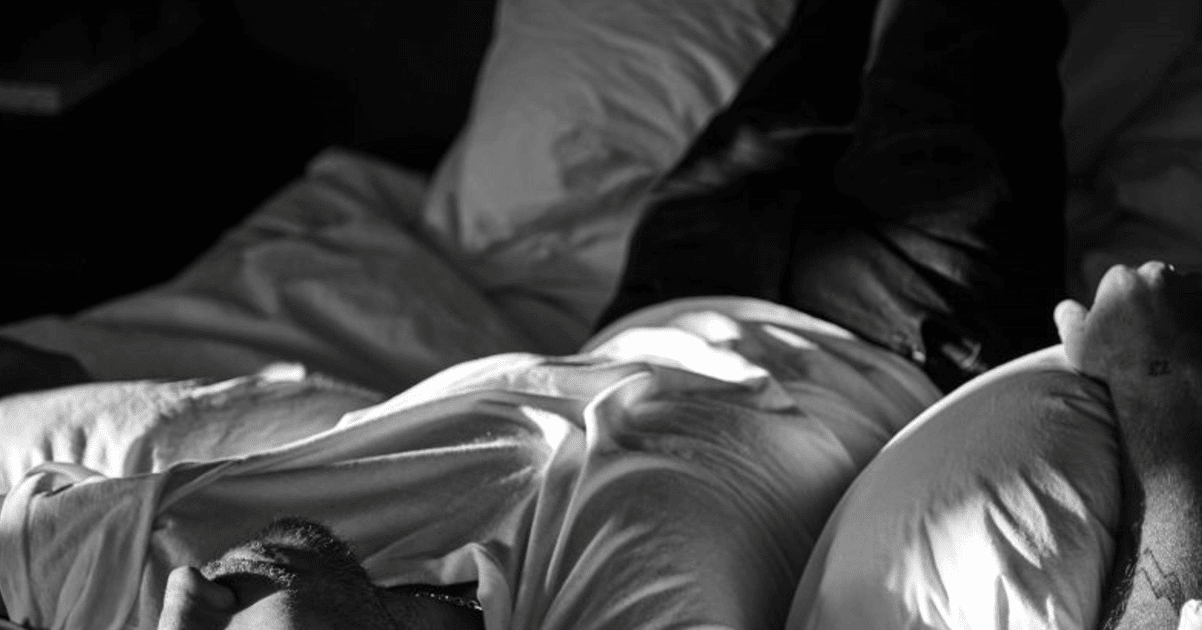

I woke up crying, drenched in sweat, my back covered in scratches.

I reached down to the floor, feeling around in the dust between moving boxes for my phone. 2:27 AM, Monday, May 29. After several hours lying awake in the dark, I’d finally slipped into a weary slumber. But my phone revealed that I’d barely slept an hour.

I was in the middle of packing up my life, only a few days from leaving the job I was told would be my career summit, one year removed from the end of my longest relationship. My dog and I would soon begin a three-day drive across the country in a tiny stick-shift Ford packed to the roof. I was headed toward a future that felt wildly uncertainbut that wasn’t why I couldn’t sleep.

Many recent nights had gone like this. I would lie in bed squirming, miserable, calling out to no one, begging to fall asleep. Eventually exhaustion would win outbut after just one or two fitful hours I would find that my hands had twisted behind my back to dig into my itching flesh, staining my short fingernails with blood. I was plagued by a mysterious malady that was slowly marching me toward a madness from which I feared I might never return.

But you wouldn’t have known from my social media feeds. I continued to tweet out stupid jokes and post sepia-filtered selfies that showed a smiling guy saying goodbye to one chapter of his life and looking ahead excitedly to the next.

The insufferable itch had started on my right shin a few months earlier, lingering there before migrating over to my left. Soon I was breaking out in hive-like rashes, blushes of blistering pink. Before long they were creeping up to my knees and thighs, then to my stomach, then my arms and elbows and the back of my neck. Eventually they were nearly everywhere, from the crowns of my ears to the bottoms of my feet, spotted rashes interspersed with red scratch lines that bloomed into purple bruises.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, I had been exposed to scabiesmicroscopic mites that burrow beneath your skin and cause an itch so consuming that the Latin root of “scabies” is literally “the itch,” derived from the word for “scratch.” Months later an ex who has worked in hospitals told me he’d heard scabies was so agonizing that, before it became easier to treat, it had driven many to suicide.

My scabies infestation arrived less than a year after I’d been exposed to bedbugsjust as my ex of nearly five years was moving out of our apartment, which was already one of the hardest experiences of my life. Instead of diving back into the dating world, I’d spent most of my newly single nights monitoring my bed for the slightest stir, paranoid that blood-sucking beasts were waiting to feast on my flesh. I was a wreck, and months passed before I got a full night of sleep.

And yet scabies was worse, especially because it evaded diagnosis for so long. By the time it was finally identifiedfour doctors, three biopsies, and a cross-country move laterthe lack of sleep had compounded with my physical anguish to leave me so destroyed that I couldn’t pretend to be anything else, even on social media.

I had imagined arriving in my new city and hitting the ground running, charming new friends and posting social media updates about my next chapter. Instead I was a total disaster; in every conversation with a cute stranger, in every new introduction, and at times even on social media, I was forced into honesty. I was broken open, my suffering laid bare for friends and strangers alike.

During some of the most difficult periods of my life, I, like many others, have climbed into bed, pulled the covers over my head, and yearned to hide my pain from the world. But with bedbugs and scabies, even my bed felt dangerous. I couldn’t hide, so I wore my mess on my skin. And because I wasn’t able to pretend I was someone elsean edited, more polished version of myselfI forged much more honest and real relationships during this time. I couldn’t curate myself, so I had to show up exactly how I was: hurting, wounded, and messy.

It was horrible. And liberating.

Even our safest spaces aren’t guaranteed to stay that way, no matter how much we try to hide or protect ourselves from being truly seen. If we want to be resilient and real, we need to face the fact that being real means taking risks. Hiding and editing won’t save us, because we are always at risk of being exposed. The answer, then, is to embrace openness, letting others see our messier sides more often, not just when we’re in crisis.

In the age of filtered selfies and pristine personal brands, it can be profoundly hard to let people see our imperfections. Even when we do share some of our challenges online, we often turn them into jokes, or something making us stronger, hurdles we’re leaping over on our way to our best life. It feels hard to say, “I’m not okay right now, and I don’t know when I will be.”

Scabies and bedbugs bookended one of the hardest years of my life, when both my job and relationship unexpectedly ended. One of the most challenging things about them was that they occurred at moments I was preparing to reenter the world, when I wanted to start fresh and “rebrand” myself as strong, pulled together, and better than ever. But that glossy version of myself didn’t, and couldn’t, exist, which forced me to learn how to be more vulnerable with others.

Vulnerability is hard, especially for many queer people. I learned early that men were only supposed to be and feel certain things and that, in order to survive as a queer person in a heterosexist world, I would have to conceal the softer, more sensitive aspects of myself. These impulses remain deeply ingrained, and I don’t think they will ever completely go away. But I don’t want them to be my defaultor anyone else’s. Even though vulnerability scares the hell out of me, I want queer people, and all people, to be able to be our full selves. In all our pain, in all our joy, in every complicated feeling.

To confront that fear, this monthly column will consider how we can let ourselves be messy, complicated, and vulnerable. Each month I’ll talk to someone about a time they felt truly exposed and what they learned from it.

On that sleepless night in late May, lying in the bed my ex and I used to share, I remembered what I learned from The Velveteen Rabbit, the story my mom would read to me when I couldn’t sleep as a child.

In my favorite part, the toy rabbit asks an old rocking horse what it means to be real.

“Real isn’t how you are made,” the horse replies. “It’s a thing that happens to you.”

The rabbit then asks if it’s painful or uncomfortable to become real. Sometimes, the horse says, but “when you are real you don’t mind being hurt.”

In order to become more vulnerable and real, we must allow ourselves to become not only worn and ragged, but also soft like velveteen itself. We must let go of our desire to be seen as strong and stitched together, and let the stuffing spill out of our seams. We must embrace the discomfort of sharing not just the flattering or neutral parts of our lives, but also the mess. And we must allow ourselves and others to be works in progress, to be wounded, and to be human. At times this will be painful and uncomfortable, but now, perhaps more than ever, it feels essential.

Want to get exposed? Email Chris at [email protected] with a short description of a time when you felt truly vulnerablein either a positive or a painful way (or both).

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Culture

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox