When she was sixteen years old, Rosalynde LeBlanc saw the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane modern dance company perform D-Man in the Waters, Jones’s tribute to his late partner, Zane, who had died of AIDS, and to troupe member Demian “D-Man” Acquavella who was likewise very sick (and would soon die of) the same cause. That piece not only won Jones a 1989 New York Dance and Performance “Bessie” Award, but it also changed LeBlanc’s life. She joined Jones’s company, staying for six years, and later danced with Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project. Today, she teaches dance at Loyola Marymount University. She is the co-director of the extraordinary documentary now in theaters (and streaming virtually through some of them) Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters, a record of her own students preparing to perform the work, but also a history of Jones, his company and the piece, one of the best films about artists trying to imbue students with love for the same work that inspired them.

LeBlanc’s class of undergrad dancers seem stumped by her question, “What is our AIDS now?” One says gun violence, another says conflicts on Facebook and neither makes a convincing case. A savvier group might argue HIV/AIDS is our AIDS “now” (the film was shot pre-pandemic) with Black queer men in the US having an estimated one in two chance of living with HIV in their lifetimes. But these students seem too young and sheltered (Loyola Marymount is in Los Angeles, but it is a Jesuit university) to have any answers and though some of them are undoubtedly queer, they seem reticent to incorporate queer life into the discussion (as Jones, in his work and interviews, always has) though a dancer does share that one of his parents came out as trans when he was a child.

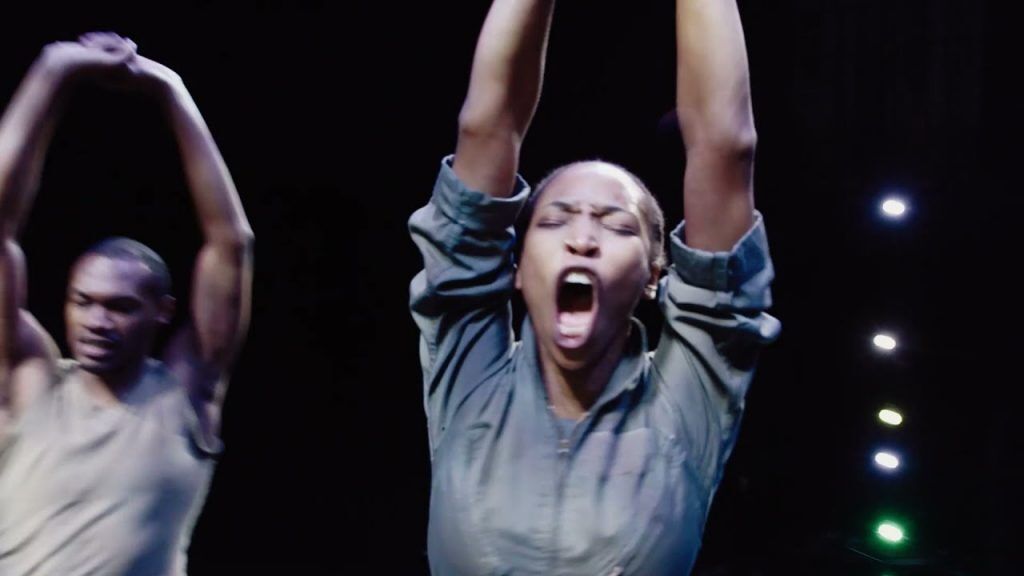

Jones, in his 60s now and having lived with HIV for decades, takes off his shoes to lead the class, at LeBlanc’s invitation, and his energy is infectious. He and LeBlanc remember one part of the choreography in D-Man in the Waters differently which shows how ephemeral dance can be–even Jones’s, which has won him two Tonys and a MacArthur fellowship. We immediately see the parallel with queer history, like the dance and Jones himself, always in danger of being forgotten by future generations, as an emotional LeBlanc tries to get her students to understand what living through the AIDS crisis was like, so they can feel this dance, not just go through its motions.

Jones, in his 60s now and having lived with HIV for decades, takes off his shoes to lead the class, at LeBlanc’s invitation, and his energy is infectious.

Jones (the one highpoint of Ailey, the otherwise dull, recently released documentary about another legendary gay Black choreographer, Alvin Ailey) is kind and generous to the students but precise in his criticism. Although his work always contained non-traditional elements, like men carrying men and women carrying men plus male performers wearing skirts (and having a fat man, Lawrence Goldhuber, interviewed in the present day as well as featured in an archival video, as a star performer), he sees the physical problem with a woman in the class supporting a taller and heavier male student. He also suggests a relative novice, Mateo Rudich, whose background is in hip hop dance, so he often isn’t familiar with the ballet elements and terms the others are, should switch roles with the student who is a dance major. Training for the new part, Rudich joyfully runs in backward circles in the studio and cinematographer (and co-director ) Tom Hurwitz moves the camera so he at times seems like he’s moving forward. Jones was right to give him a more prominent role.

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

Queer history, like the dance and Jones himself, is always in danger of being forgotten by future generations. LeBlanc tries to get her students to understand what living through the height of the AIDS crisis was like, so they can feel this dance, not just go through its motions.

Throughout the film, several iterations of Jones’s company perform parts of D-Man and other works and the original members share their memories in interviews. Seán Curran, a gay man who danced with the company in the ’80s and ’90s explains that he had seen Acquavella as a rival: someone who was similar physically but who had the onstage charisma Curran felt he lacked (in the old videos Acquavella stands out, even before we know who he is). But after performing in a duet in which they moved as one, their foreheads pressed together during the entire dance, they became close friends, at one point buying matching school girl uniforms to wear to the clubs–with nothing underneath.

Can You Bring It is full of moments that could have come from a narrative film. Curran recounts that one day Acquavella asked him what he thought the spot on his arm was and although Curran recognized it as Kaposi’s sarcoma, he told Acquavella it was probably a bruise from rehearsal. Later Jones promises Acquavella he will be on stage in D-Man and even though by the time it premieres, Demian is weak and has dementia, and Jones carries him onstage to have him do the arm movements of the piece (he is unable to do other choreography) then carries him off (an entrance and exit shared by the gay, HIV-positive dancer-protagonist in the 1997 British feature, Alive and Kicking). Acquavella died just two years after Zane. Says Jones, “We were hurting, but our work was a way to keep going.” ♦