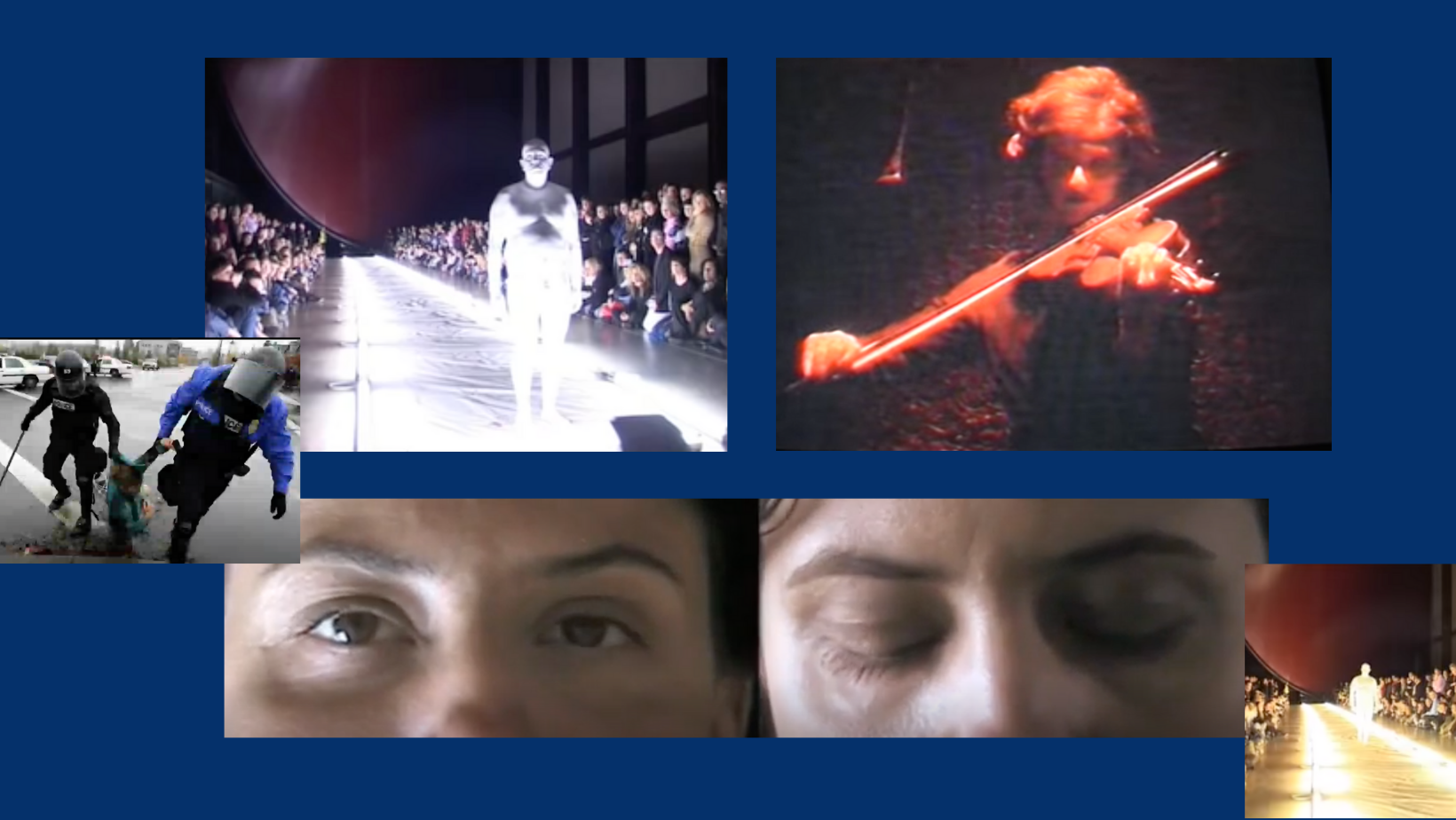

Franko B’s 2021 performance I’m Here exists in dialogue with history, both individual and institutional. Images are projected onto Franko’s body using 360° body-mapping – his own performances; politicians like Joe Biden and Kamala Harris; protests; pornography – and the piece is left semiotically open, inviting interpretation more than answers. It reckons with the artist’s own past performances, several of which use his body as a canvas.

This idea of the body as a vehicle for art has developed over time, from Yves Klein using bodies for paint, to Franko’s earlier work using blood as artistic material. As technology changes, the way in which the body can be used changes alongside it; in the 21st century, art that’s more rooted in the digital. The constant changing of images feels like browsing the endless stream of online content – it makes sense for the body to be projected onto like a TV screen or a browser. These developments also reveal ways in which the world has moved on since he performed these older pieces, like Oh Lover Boy (2001-5), and I Miss You (1999-2005); the former has the artist lying down, christ-like, bleeding from his hands, while the latter takes this recurring image of Franko – nude, painted white, bleeding – and places in the context of a catwalk. I Miss You features at the end of the new work, a kind of remake, artistic self-cannibalism that mirrors the changing place of both the artist, and the world that they inhabit.

I’m Here is a kind of 21st-century reprise of Franko B’s bloodletting work from the 90s and early 2000s, using advances in technology to reframe the ways in which the body can be used as a site of politics and resistance in live art, and understand Franko’s old work in a new way. In turn, the continuing changes in Franko B’s work capture a wider change across queer art, and the ways in which it relates to illness, and the politics of the body.

The constant changing of images feels like browsing the endless stream of online content – it makes sense for the body to be projected onto like a TV screen or a browser.

I’m Here is a striking example of the ways in which the body can be reconstructed with a new meaning. For decades of Franko’s performance work, the body has remained nude and painted a stark white, creating the image of living blank canvas, making every change and cut all the more noticeable. But just as his practice has changed over time, the way that this body is understood has changed with it. I’m Here engages with the legacy and echoes of Franko’s work and how the art of the past can be reinterpreted in a new decade, a new century, under a different political consensus. By projecting I Miss You onto the body of its performer, I’m Here reframes Franko’s old performances as part of the continually changing idea of the queer body in art. Here, it is both a canvas and a screen, a move away from contact and towards projection. Rather than being about the loss of something – blood — I’m Here is about accumulation, the addition of images, the layering of ideas.

Here, the queer body is both a canvas and a screen, a move away from contact and towards projection.

While illness hasn’t historically been a permanent fixture in queer art, the AIDS crisis and the decades in its wake have led to a reckoning with these ideas. Queer art has always, in a sense, been haunted by lives lost. Artists have often directly responded to the ways in which it impacted the perception of queer bodies by foregrounding the presence and use of blood, and these bodies’ relationship to illness. Art produced that emphasized these bodies was inherently political, an act of resistance. Of course, these definitions of queer bodies, and the extent to which they were able to respond to the AIDS crisis at the time or since, are somewhat narrow. They’re informed heavily by the conservative politics of a small number of countries – chiefly American and the United Kingdom – something that speaks to the fact that platforms were available to mostly white and male artists at the time.

There’s no physical bloodletting in I’m Here. Instead, scars and moments of bloodletting from Franko’s past performances are projected onto his body, apparitions from a queer past that was defined by bloodborne illness. This makes the reuse of Franko’s bloodletting work in I’m Here particularly nuanced and complicated: with the old art projected onto his current body, the spectre of the AIDS crisis is brought back to life, reminding us that it is still very much with us.

The most (in)famous example of queer live art about blood, and the political outcry surrounding it, is Ron Athey’s Four Scenes From a Harsh Life (1994). The piece created a moral panic around the idea that Athey, who is HIV positive, was exposing the audience to “AIDS-tainted blood,” even though the blood used came from one of Athey’s HIV-negative collaborators, Divinity P. Fudge. The legacy of panic around the blood of queer men still persists; in the US and Canada, there’s a 3 month abstinence rule for queer men donating blood. A similar rule was recently overturned in the UK, but queer men were still prohibited from donating plasma during COVID-19. That’s what makes the distorted, reappearing scars in I’m Here so politically potent; it becomes an act of reopening old wounds, and all the damage that comes with them.

Disease doesn’t always generate this kind of response. For all of the damage done by the Spanish Flu in the wake of the First World War, there’s little art – from the time or since – that grapples with it, while there are countless responses across all artistic forms to WWI. An exception to this rule is Edvard Munch’s Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu (1919). The gulf between responses to the war and to the illness that ravaged the world after it is the beginning of a complicated idea around the ways in which illness is responded to in art, and the relationship that this has with politicised bodies.Historically, art about illness has focused on loss of life, and apocalyptic imagery associated with it; from Bruegel the Elder’s The Triumph of Death (1562), to the 18th and 19th century paintings of the Dance of Death. Throughout the 20th century, as illness and disabled bodies became politicized—as they did during the AIDS crisis—the art being created changed in order to reflect this; bringing to the forefront the realities of living in ill, queer bodies.

More contemporary artistic responses to epidemics explore the idea of illness creating an othered body through the prism of identity. The bloodletting work of Franko B and Ron Athey illustrates how the idea of HIV and contagion change the ways in which the queer body is perceived; for example, the work by Kia LaBeija, reframes racialized narratives around an ill body in her photography. These responses to COVID are often less about the body – the nature of the illness and its indiscriminate nature – because COVID doesn’t other the body in a way that HIV/AIDS historically has. Additionally, by being airborne rather than bloodborne, COVID requires a different kind of artistic response; there are examples of what this might look like in both historic and contemporary queer art.

Michael Curran’s 1994 piece Amami Se Vuoi explores the idea of fluid exchange beyond blood in a way that’s both intimate and somewhat unsettling; there’s an air of aggression to it, even with a willing and open mouth accepting something primal and bodily from a partner. While it doesn’t impact queer people in the same way as HIV, COVID-19 has still been responded to in unique ways by queer artists, reiterating how queer bodies can exist as sites of political action in art.

Much of this work shares a relationship to history, from the dialogue that Ron Athey enters into with saints and the idea of religious ecstasy, echoed by Franko B in Oh Lover Boy (2001-5), to the ways in which Martin O’Brien’s work has responded to the legacy of Bob Flanagan. The intersection between art and chronic illness in Flanagan’s work is a question of agency, and finding a kind of liberation in submission all of which he lays bare in the poem ‘Why?’, which features lines like “because I felt like I was going to die/because it makes me feel invincible/because it makes me feel triumphant/because I’m Catholic.”

O’Brien’s art has evolved over time as his own relationship with his body, and time, has changed. The 2018-20 piece, Until the Last Breath is Breathed, captures the changing dynamic of his work, as he moves beyond the life expectancy of someone with cystic fibrosis, and what he’s gone on to call “Zombie Time.” These are themes that have become increasingly vital in the time of COVID, and his work has gone on to reflect this.

[Queer performance art] constantly invokes history, looking to the future, and what it is that we might leave behind for others, for our ghosts, for the planet.

The Last Breath Society (Coughing Coffin), a 2021 group show at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London which featured one of O’Brien’s performances as a centerpiece, captures the various ways in which queer artists have responded to themes of illness, breathing, and isolation. The show brings together a wide variety of responses to ideas of queer life, death, and rebirth, on both micro and macro scales; from personal responses to death and what we leave behind in Lechedevirgen Trimestigo’s Last Will, to the relationship that the earth has with illness and climate change in You will not feel this way forever by Nicholas Tee. A video piece by Frank B, Time Space Nothingness (2018), explores loneliness and timelessness with footage of solitary figures by the sea, as the artist reads text over it. By placing art about loneliness or environmental catastrophe alongside a variety of pieces on physical illness, ideas of what it means to be ill are reframed and placed into new, politically urgent contexts. Rather than simply amplifying the poignancy of Franko’s piece about loneliness, the show proffers a new understanding of what we consider to be an “illness” or epidemic, from the impact that isolation can have to the idea that the planet itself is sick.

By placing art about loneliness or environmental catastrophe alongside a variety of pieces on physical illness, ideas of what it means to be ill are reframed and placed into new, politically urgent contexts.

Coffin captures something vital about the changing nature of queer art: the ways in which we define ideas of queerness, bodies, and illness itself keep changing. It constantly invokes history, looking to the future, and what it is that we might leave behind for others, for our ghosts, for the planet. Noemi Lakmaier’s In Progress meanwhile uses a split-screen to explore the assumptions and contradictions of gender and identity as something that’s constantly in the process of change.

As our understanding of queer life and art continues to change, we have a greater need for responses that can capture the multitudes inherent in these identities. Some of this is obvious: you can’t use the body-as-canvas to respond to different illnesses in the same way, and there’s a greater need for diversity in the kind of bodies and experiences seen in this art.

To understanding the relationship that queer art around illness has with bodies, it’s vital to understand the kinds of queer bodies that are most often represented: white ones. What’s striking about Coughing Coffin is the way in which it diversifies what’s understood as The Queer Body. As the world changes, queer art needs to change with it, and the narrow prism of what the queer body meant decades ago needs to develop in a way that captures the multifaceted nature of contemporary queer life. It requires, along with changing how these bodies are perceived, changing the kind of bodies that we see; to look at the history of this kind of art is to look at the bodies that have so often been absent from it.

One of the most powerful moments of I’m Here comes at the end of the performance, when a projection of I Miss You is beamed onto Franko’s body: his past self literally brought back to life on his current one. The sequence from I Miss You grows smaller and smaller, a striking image that seems to capture something about what we carry with us, and how we change. In the time since I Miss You was first performed, the world has changed, and the layers and contradictions in I’m Here capture the ways in which queer art has to change with it.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox