In gay culture, the idea of dating your twin remains eerily relevant. Few authors, however, have taken up the challenge inherent in this queer trope. Sure, there are creepy twins aplenty in horror films—the iconic duo in The Shining, the brothers in Dead Ringers, the sisters in Don’t Look Now—but in the realm of horror fiction, few novels succeed in transforming the inherent eerieness of queer twins into a catalyst for a satisfyingly horrific conclusion.

And then, there’s Thomas Tryon’s The Other.

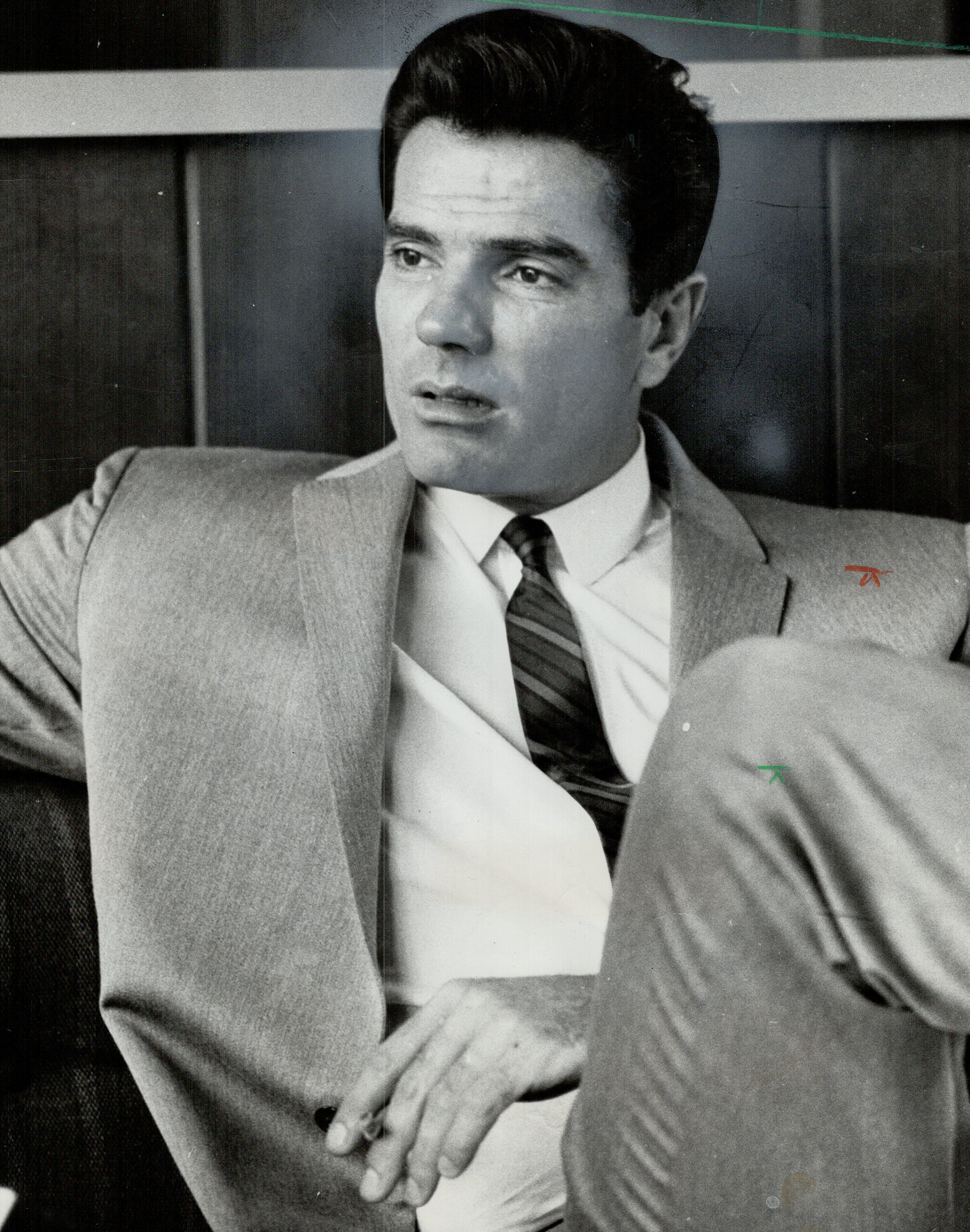

The Connecticut-born Tryon, who attended Yale and served a term in the Navy during World War II, started out life as an actor. But after a handful of harrowing experiences in the screen trade—most famously on 1963’s The Cardinal, where he was verbally abused by director Otto Preminger—he turned his dramatic efforts toward fiction. Luckily, he was amazing at it. Before dying due to complications of AIDS at the age of 1965, Tryon managed to pen 8 novels, along with a few short story collections, in the span of 20 years.

Tryon’s pivot was a wise one: during the 50s and 60s, being an all-but-out gay actor wasn’t exactly a walk in the park. After a three-year marriage to a woman, Ann L. Noyes, and two decades as an actor, Tryon turned his attention to writing, coming out with 1971’s smash success The Other. He also started dating men, if not exactly openly: first the “Chorus Line” dancer Clive Clerk, then the gay porn actor Casey Donovan.

Related:

This Overlooked Novel is an Erotic, Gripping Look Inside a Boy’s Military School

Torless’s confusion is hardly limited to his queer sexuality.

The Other is nothing if not informed by the sometimes erotic doublings of self and image that are part and parcel of queer culture: we open on two twins who share a secret language, and a “game” they’ve been taught by their Russian immigrant grandmother. The game involves a kind of transposition: you pick an object, and then you try your hardest to think of what it would be like to be that object, and then you become it. It’s an escape we see Niles, the “good” twin, indulging in time and again, while his bad seed brother Holland gets up to all kinds of bloody tricks. But that’s hardly the sum of it: The Other is full of perverse twists and a penultimate act of violence that literally made me gasp. It’s no wonder the book was quickly ranked among Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby and Maxwell Anderson’s The Bad Seed as game-changing horror. The culture was ready for the kind of horror fiction Tryon wanted to write: a kind of horror informed by secrecy, queerness, and deviance.

The Other isn’t just a tightly-written thriller that keeps you guessing: it’s novel that details the systematic destruction of a family, by its youngest sons. When the book opens, evil twin Holland (it’s strongly implied) has put his cousin to death, making it look like an accident. Later on, we learn that Niles and Holland’s father met a similar fate recently, as well as neighbor, the family cat, and countless others. By the end of the book, it’s clear that no member of the Perry family is meant to survive the blight of the twins: especially not their sister’s new baby, who meets an especially grisly end. All Niles and Holland care about is each other: they’re all the family they need. And as the chilling end of the book approaches, the reader understands that Niles and Holland’s relationship to the family is as outliers. They refuse to fit in with the Perrys to the point where they become dead set on ending the family line once and for all.

Some queer writers make their inability or lack of desire to continue the family line a source of anxiety. Others accept it happily—Alison Bechdel’s description of herself as a “terminus” in Are You My Mother? comes to mine. Still fewer use the medium of horror to stage an attack on the cozy concept of the American family. Taking from the unsettling genius of Levin’s horror writings—both Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives—Tryon’s The Other paved a new kind of uncanny path for modern horror. The terror of the book doesn’t, for the most part, lie in haunted spaces or supernatural events. It grips you precisely because it speaks to a queer desire underlying so much iconic horror from the stories of Edgar Allan Poe to the films of Clive Barker: it attacks the very concept of the family.

Tryon died, as many men of his generation did, far too soon. He packed a lot into his short life, and his horror fiction, including The Other, Harvest Home, and Night Magic, shows us the best of what he could do. It’s only a pity he couldn’t live to do more. ♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox