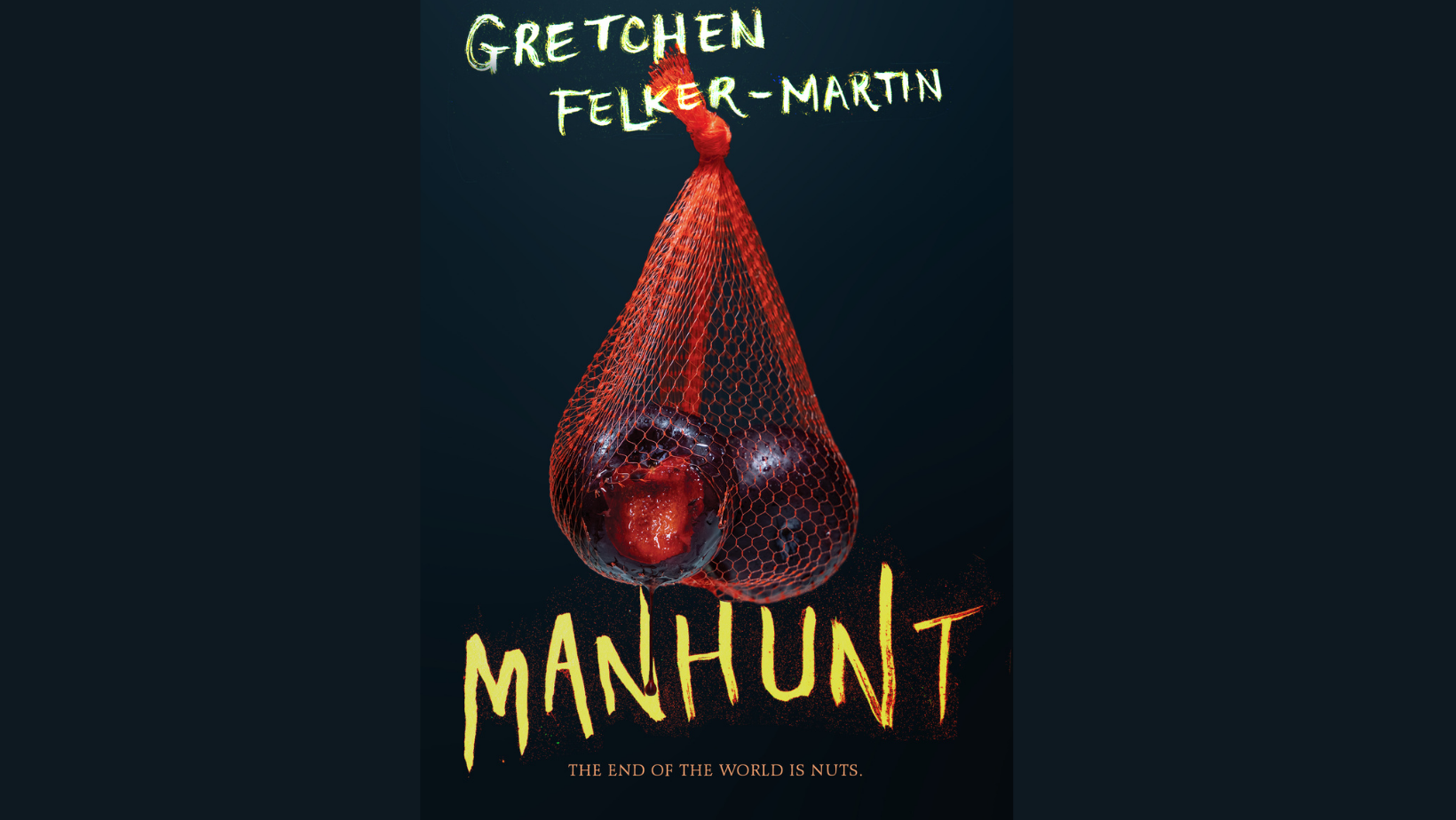

As one of the leading provocateurs of the queer horror fiction scene, Gretchen Felker-Martin is no stranger to abject controversy. Gretchen’s new novel Manhunt, which debuts tomorrow, follows a clutch of trans characters trying to survive amidst a devastating virus while outrunning murderous TERFs in an apocalyptic New England. Bathed in splatterpunk and a cinematic sensibility, the novel is an arresting exploration of the question “what if men would just go away?” It puts Y: The Last Man to shame (while inspiring renewed interest in its superior predecessor, The Screwfly Solution.) Trans women are the current epicenter of a poisonous moral panic, and trans women artists are uniquely positioned to tackle the failed essentialist fantasies of second-wave feminism. Gretchen has risen to the challenge with demented aplomb. I spoke with her about her practice, influences, and artistic desires.

Annie Rose Malamet: Before we dish about your upcoming novel, I want to talk about your origin story. More specifically, I’m interested in how you follow in the tradition of great New England Horror Writers (girl Stephen King, hello.) New England is a spooky place, steeped in ghostly history. Is this something you’ve thought about or influenced your practice?

Gretchen Felker-Martin: Yeah, absolutely. As a kid I ran pretty much wild in the woods; we lived way, way outside of anything you could call a real town. No supermarket, no businesses to speak of, just 600 or so people spread out through the forest. I’d take my dog and hunt for snakes and newts, or climb trees, or go stare into little ponds and see what was going on in there. That visual palette, dead leaves and moss and fiddleheads and lady slippers, that was very influential to me, and when I learned as a little kid that we had taken all that land from the Abenaki and the Pennacook, that had a profound impact on how I saw it. As far as I’m concerned, New England is Mordor. It’s where we poured onto this continent and commenced ruining the next four centuries of human history. Of course it’s haunted. There’s nowhere more haunted in the world, and every single picturesque little downtown area and whitewashed clapboard church is dripping with it.

What are some haunted New England books or texts that you’ve drawn inspiration from?

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

For me, it’s got to be IT and Moby-Dick. Stephen King is inescapable when you’re writing horror set in New England, and I grew up on him, and I still love him. I read IT when I was the same age as the kids it’s about, which was a really formative experience for me, and again it’s so connected to the woods and marshes of New England, the tenuousness of human life here. King really understands what we as New Englanders don’t want to talk about or look at, and what happens in those dark places we ignore. He also understands the exact ways in which New Englanders are deeply, hatefully prejudiced. With Moby-Dick, it’s the fatalist melancholy of the New England temperament that keeps me coming back to the book year after year, our endless love affair with the sea, which is really our love affair with the void. From Hell’s heart I stab at thee, etc, etc. There’s also a book called American Indian Myths and Legends by Alfonso Ortiz and Richard Erdoes, parts of which deal with local myths, Abenaki myths, that I was given as a kid, and the stories about Gluskabe and the baby and how Coyote and Wolf made the world were early favorites for me, and I think I still really want to emulate the arbitrary suffering and tricks of fate that animate those stories.

Bathed in splatterpunk and a cinematic sensibility, the novel is an arresting exploration of the question “what if men would just go away?”

Stephen King is a favorite of mine as well, despite his embarrassing Twitter presence and his bizarre fatphobic misogyny present in many of his novels, including IT. You’ll forgive me for the hot button question, but this is an issue I’m forced to think about so often these days. How do you personally reckon with difficult work made by artists with “problematic” histories or opinions? For example, I know you’re a fan of Anna Biller, a director who recently hinted at some of her TERF leanings.

I would say I’m very pragmatic about it. Millions and millions of people hate me just for what I am — trans and fat and a woman — and if I took it personally and let it scare me away from their work, I’d be cutting off my cultural literacy almost completely. King writes about fat women very cruelly, and I realized that even as an eleven-year-old, that this man I admired and wanted to emulate seemed to see my body as an object of pity at best, contempt and self-loathing lust at worst, and it’s sad that that little girl had to internalize that it was normal for the authors and directors she loved to hate her or to feel disgusted by her, but that’s the reality of loving art when your body is seen as aberrant. As an adult of course I’ve put in the work to find smaller independent art by people whose experiences reflect my own, people who aren’t disgusted by bodies like mine or who are capable of interrogating their learned disgust or self-loathing, and that’s been tremendously meaningful and healing for me. With Biller specifically, I’ve known she was dim and kind of homophobic since I first found her online presence, but what are you going to do, you know? The Love Witch is great. I saw it in theaters twice.

Your new novel, Manhunt has garnered some preemptive social media controversy from other queer and trans people. It was quite disturbing to watch a piece of art be judged by the court of queer public opinion before anyone has even had a chance to read it. Given that one of the authoritarian factions in your novel is comprised of transmisogynist cis women, was this reactionary strain something on your mind while you were writing?

This is definitely my post-online harassment book. (Laughs). By the time I had the idea for Manhunt I’d already dealt with targeted harassment from TERFs, from fatphobes, from the sort of irony-poisoned eighth-tier hangers-on to podcasts like Chapo Traphouse and Red Scare, right-wingers, and other queer and trans people as you say, primarily those who object to being told they shouldn’t try to get their fellow queers fired or beaten for reading the wrong kind of Homestuck fanfiction or whatever. So yes, it was on my mind when I started writing the book, and pretty much from the moment I announced it I started hearing from people saying “well this plague would kill such and such a group of people, so you must want to kill them in real life!” and it was just incredibly tiresome and upsetting. I think that kind of censorious impulse comes from a lack of control in one’s own life, so you start looking around like okay, well who’s vulnerable enough that I can control them? That kind of willfully ignorant and hateful mindset was what I wanted to capture with the book’s antagonists.

“Millions and millions of people hate me just for what I am — trans and fat and a woman — and if I took it personally and let it scare me away from their work, I’d be cutting off my cultural literacy almost completely.”

I’ve been reading my digital copy of your novel, and I’m most struck by how cinematic the violence you write is. Which obviously makes perfect sense to me as I know film criticism is part of your artistic practice. In your fiction writing, are you considering filmic portrayals of violence? Which films or directors stick out to you as inspirations?

Movies definitely mediate how I picture and write violence, but what I’m always chasing when I watch violent movies is catharsis for the feeling of the violence I’ve experienced in life. I want to make it feel like that, to communicate that violence is an intimate interpersonal thing, that it expresses power and disgust and desire. For me, the director who does that over and over again in his movies is David Cronenberg, who gets that violence is calamitous and psychically and physiologically altering. Lars von Trier, particularly with Antichrist, that scene where Charlotte Gainsborough drives a millstone through Willem Dafoe’s calf has been with me for years and years now. That’s a high watermark, to me. That and in Mary Harron’s American Psycho where the sex worker played by Cara Seymour scratches Patrick Bateman’s face and he loses his mind. I love that. Oh, and I really can’t talk about this without mentioning the time-lapse action sequence in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the Coppola movie. It’s so lush and textured and indulgent, and that movie really informs so much of what I value aesthetically in prose. Maximalism. The grotesque. Excess.

“As far as I’m concerned, New England is Mordor.”

Another aspect of this book that is sticking to me are the overt references to internet jargon, culture, and spaces – particularly those that are known for targeting trans people and women (for example, the use of the incel mononym “Chad”). Being that this is such a current text, how do you want this story to stand the “test of time?” How do you envision it functioning in ten or fifteen years?

G: I think for me the test of time isn’t very important. Not to get heavy but I never expected to live to thirty, so whatever they want to do with my shit when I’m gone, that’s fine, or if I’m still alive that’s still fine. They can forget it or steal it or whatever they want. I wrote the book for myself and for trans women like me at this moment in history, and we’re all so immersed in the sewage of internet culture, it felt impossible for these characters not to talk that way and understand those things. If it ages poorly, it ages poorly, but you know, people still watch Seinfeld. They still read Shirley Jackson, and the context for her stories became more and more about her own agoraphobia as her life went on. I think an intensely personal and of-its-time thing has certain strengths that more generalized, popularly appealing art doesn’t. Really though, in ten, fifteen years I hope with all my heart that people who read Manhunt are like “Wow, were we ever that scared of TERFs? Do they even exist anymore? Weird book.” I hope that’s how it ages.

There’s a complex interplay between sex and violence in Manhunt. I’d expect nothing less from you, obviously. There’s this incredible moment right in the beginning where one of the main characters, a trans woman, is facing off with a cis woman TERF who is actively trying to kill her. As Fran is fighting for her life against this attacker, she imagines the TERF holding a riding crop above her quivering ass and starts to get horny. It’s a short and loaded moment wherein shame, violence, arousal, and queerness are jumbled in this gorgeous cacophony. I want to know more about your process in writing these scenes and considering the relationship between desire and fear.

“I wrote the book for myself and for trans women like me at this moment in history, and we’re all so immersed in the sewage of internet culture, it felt impossible for these characters not to talk that way and understand those things.”

I’m speaking for myself here, but I think it’s not exactly to say a lot of trans women grow up very intimate with feelings of self-loathing, and as an adult, sometimes having those feelings confirmed by an outside party, especially an authority figure, can feel perversely gratifying, like “oh okay, I’m not crazy, I’m not making up how horrible I am, and this person here is going to assume responsibility for that by hurting and degrading me.” It’s an erotic dynamic; you don’t need to look any further than Nancy Friday’s My Secret Garden where Holocaust survivors talk about their sexual fantasies about their captors and torturers, about the worst experiences of their lives and how they came to get off on the aesthetic and sensual memory of those experiences. I think that’s powerful, getting off to the people who wanted to exterminate you. And of course, the TERF fixation on trans women is sexual; it’s intensely sexual. They concoct these elaborate fantasies in the form of conspiracy theories about how hypnosis sissification porn is stealing away men like some kind of Invasion of the Body Snatchers scenario, they spend all their time ranting and raving about us until their spouses leave them, until their lives fall apart, until they have nothing and no one in their lives but their embittered cult ideology. We’re their fetish.

And finally, what are your dream project plans for the future? What are you working on now?

Right now I’m working on THE CUCKOO, a sort of, like, Stepford Wives story set in a conversion therapy camp for queer teens in the early 90s. Really really intense body horror, teen angst, teens hurting each other and fucking up and falling in love. I think it’s scheduled for 2023, but don’t quote me on that! After that’s done I have a million things I want to do. I have a book about Venetian flagellants, a dinosaur horror-fantasy, a magical girl body horror story a la Sailor Moon, a book about a billionaire who pays a bunch of fuckups to commit suicide so they can build him an estate in Hell before he dies. The one I keep thinking about, though, is a horror story about medieval sappers, the guys who dug under castle walls at a point in history where really we were not at all good at making sure tunnels didn’t collapse, to plant bombs and undermine fortifications. I had this idea for a story about a couple of lovers who do this for an English nobleman’s army in the 1500s. Getting stuck underground is one of my longest-lasting phobias, and I love writing medieval horror. It’s such a rich period.♦