Superheroes have long been established as one of popular culture’s many cornerstones, and of them, Bob Kane’s Batman could arguably be considered the most popular — but also, maybe the darkest. Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy (2005, 2008, 2012), and more recently, Matt Reeves’ The Batman (2022), have both delivered more brooding interpretations of the famous comic-book character, both largely becoming responsible for the hero’s moody reputation. However, long before Nolan or Reeves got their hands on Batman, the superhero was portrayed in a far more lighthearted fashion, embracing the inherent campness that comes with a grown man fighting crime in his tights.

This was certainly the case in Leslie H. Martinson’s Batman: The Movie (1966). The first feature-length Batman film saw Adam West in the title role and provided so much superhero silliness that it verged on parody. Later, Tim Burton’s films, Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992), would offer a far more gothic take on the character, although they too had an unmistakable flamboyance to them. Yet, it was Joel Schumacher who really took this one step further with Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997), both of which exhibit an overt queerness that simply cannot be denied.

RelatedNobody would call an orange juice the “Batman special” if they didn’t want the audience to laugh at it.

This is especially the case for Batman & Robin, which is notorious for many things, but notably for being considered one of the worst superhero films of all time. However, this unfair dismissal neglects to appreciate the value of its queerness, or maybe this is part of the reason why it was received so poorly. It’s certainly more extravagant than its predecessor, but it also shares a lot of similarities with it. As it was in Batman Forever, where Schumacher first brought his queer influence to the franchise, even if it’s far more obvious in his much-maligned follow-up.

Entertainment with an edge

Whether you’re into indie comics, groundbreaking music, or queer cinema, we’re here to keep you in the loop twice a week.

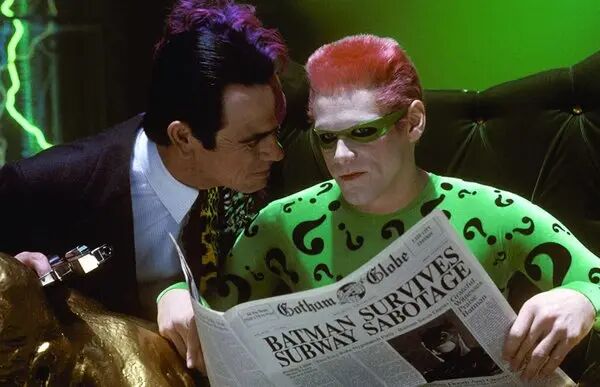

Schumacher clearly recognized the utter camp value that the likes of Michelle Pfieffer’s iconic performance as Catwoman created for Burton’s films, and ran with it in his own. In Batman Forever there’s Jim Carrey’s appropriately eccentric Riddler and Tommy Lee Jones’ truly manic Harvey Dent, aka Two Face. The colorful villainous duo really light up the screen, complete with some serious homoerotic undertones too. Next up, in Batman & Robin, Arnold Schwarzenegger delivers every ice pun known to man as the farcical Mr. Freeze. But better yet, it was Uma Thurman’s turn as Poison Ivy that really turned up the camp factor, proving to be absolutely mother (nature) for her performance. Whether it’s her over-the-top entrance –– where she emerges from a pink gorilla costume, inspired by Marlene Dietrich in Venus Blonde (1932) –– or the way she tempts her victims with a sultry kiss from her venomous lips, Schumacher’s vision for Poison Ivy, and Thurman’s subsequent performance, gave the gays everything they wanted.

Poison Ivy reveals even more of the film’s queerness as she unlocks an interesting rivalry between Batman and Robin. As they battle for her affection they drift apart, but are they really fighting over Ivy, or just jealous at the thought of each other with her? Just like the homoerotic undertones seen between Riddler and Two-Face, Batman and Robin also features that same subtext for its titular characters. And it’s these added layers to Schumacher’s characters that really take things from purely camp, to unapologetically queer.

Whether intentional or not, Batman Forever continually plants the seed of this relationship. Before Chris O’Donnell’s Robin (a gay awakening for many queer kids) becomes Batman’s official sidekick, he’s a part of his family’s circus act, the Flying Graysons. In his first appearance, he wears the classic green and yellow Robin suit –– which leaves very little to the imagination –– and even has a single fruity earring in too. Later, and after the tragic death of his family, Bruce offers to take him in at Wayne Manor. However, Bruce is only successful in getting him to stay after enacting full sugar-daddy mode, using his extensive collection of motorbikes to persuade him.

Long before Nolan or Reeves got their hands on Batman, the superhero was portrayed in a far more lighthearted fashion, embracing the inherent campness that comes with a grown man fighting crime in his tights.

Succumbing to Bruce’s money and charm he stays, ultimately discovering his superhero alter-ego. He eventually goes on to join him in fighting Riddler and Two Face, as “not just a friend, a partner.” Their relationship, both as a vigilante team and as “partners” continues to develop in Batman & Robin and gives even more weight to an earlier comment in Batman Forever when Batman admits: “I haven’t had much luck with women.” Of course, none of this confirms that Batman and Robin are gay, but it also doesn’t confirm that they are straight.

One of the biggest criticisms of Schumacher’s directing tenure is the batsuit costume design, which includes the infamous bat-nipples—but even this can also be interpreted as one of the more apparent examples of the film’s queerness. Many negatively cite Batman & Robin as the first film to feature this questionable costume design, but it was actually first seen in Batman Forever, with Val Kilmer debuting the more suggestive suit. It’s undeniable that in Schumacher’s films there is a much more enhanced look to both Batman and Robin’s costumes. The director has previously stated that the suits are based on Greek statues with perfect bodies and that they are “anatomically erotic.” He really makes sure the audience doesn’t miss this attention to detail too, including several close-up shots of the heroes as they suit up, highlighting every intimate angle –– bat butt-cheeks included.

In Batman Forever, Nicole Kidman’s Chase Meridian even comments on the suit, mentioning the appeal of its “black rubber,” before running her hands over it. This of course has additional connotations when considered through a queer lens and could inspire readings likening the costume to rubber and PVC fetishism. George Clooney, who replaced Val Kilmer in Batman & Robin, drew similar parallels. In an interview with Barbara Walters, he famously revealed that his Batman was gay. “Think about it, I was in a rubber suit. I had rubber nipples. I could have played him straight but I didn’t. I made him gay.” So whether or not Schumacher’s intention was to make these suits more sexual or arousing, his influence as a gay man and his appreciation of the male body is evident in their design.

But this is what’s so special about the queerness in Schumacher’s Batman films: it’s natural. Schumacher admitted that it never occurred to him not to put nipples on the men’s suits, because he “didn’t know that the male nipple was a controversial body part,” because obviously to him, why would they be? It’s fairly likely that Schumacher never set out to make Batman gay, but his Batman films became queer due to his influence. He let his experiences, tastes, and ideas as a gay man shape his creative vision, and for that, his Batman films –– despite their unfair reputation –– will always have value. ♦