Going to see Chicago in theaters in 2002 is a memory that, for whatever reason, remains etched in my brain. I went with my two best friends at the time: in those days, we composed a group of bored preteens who went to the movies mainly to do other things, like hang out at the mall, eat Taco Bell and Orange Julius and f*ck around. But Chicago was an event: we were there for the movie, for once. It wasn’t like the 35 times I’d gone to the Hampshire Mall to see Down to Earth—this was a big deal.

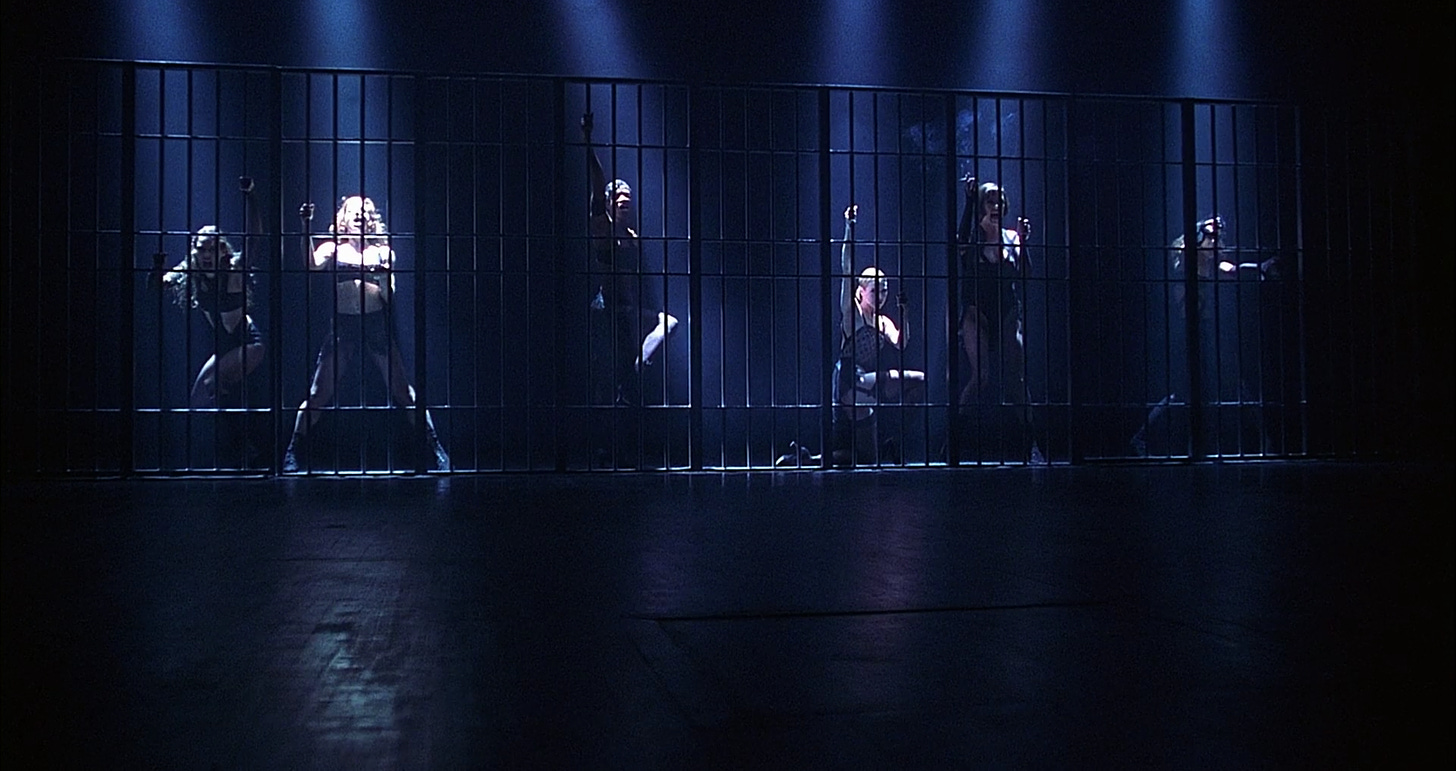

It was a cultural event, too: we were there not just to see an adaptation of a musical that had been running for years already on Broadway. We were there to see an updated version of the show made palatable for us: preteens with no real relationship to Broadway or live theater, but predisposed to love musicals with everything in us. We’d loved Moulin Rouge the year before, and Chicago promised to give us something of the same thrill. It was a musical shot like a music video, and we were there not just to hear the story of jazz-age killer Roxie Hart (Renee Zellweger) and her rival and eventual costar Velma Kelly (Catherine Zeta-Jones.) We were there to see Queen Latifah as Matron “Mama” Morton, the “countess of the clink”; to see the iconic 2000s pop star Mýa as one of the girls of the infamous “Cell Block Tango.” We were there to see cameos by Lucy Liu and Taye Diggs, and we were there to see girls shake their asses in sequined outfits and whisper “hotcha…whoopee” while gyrating on each other.

Basically, we were there because it was gay. Very, very gay. As a teenage girl, you don’t get excited about a 1920s-set prison musical that’s 90% isolated shots of women’s thighs unless you’re either gay, or in denial.

Related:

This Experimental Film Tried to Be Homophobic and Ended Up Being Homoerotic

Possibly the classiest erotica you’ll ever watch.

We were both.

On the face of it, “Chicago” is a musical about women killing men, with the understanding that most men—if not all—totally deserve it. “It was a murder, but not a crime,” the chorus sings in “Cell Block Tango” as Velma Kelly describes how she walked in on her husband and sister in flagrante delicto, shooting them dead on the spot.

And they’re right. One of the most baffling injustices of this culture is the fact that men can do just about anything they like to women—fuck around with them, break their hearts, two-time them, leave them for the babysitter—and women, for their part, have basically no recourse. And sure, the #MeToo movement helped a little. But rape and sexual coercion are not the only ways in which men hurt and destroy women: far from it. Our society, down to its very bones, is set up to reward and celebrate cowardly men who cheat, neglect their children, desert their families, treat their girlfriends and wives like shit, lie to their faces, and remarry younger, hotter models the second they’re out of the picture. “Chicago” is a blissful remedy to that, a kind of alternate universe that reimagines these terms and asks: “what if women had the power in relationships?” What if female revenge was allowed to run wild in the streets, with no consequences from society or the law?

All the men would be dead, and the women? They’d be having an amazing time.

This updated-Lysistrata premise is just about as gay as it gets. Gay men love nothing more than a vengeful, broken-hearted woman on the brink of breakdown, and queer women will never pass up a chance to watch a prison drama that celebrates hard-talking dames, thigh-flashing acrobatics, and communal female power. Chicago’s jail scenes present an Amazonian matriarchy set up to avenge even the smallest of slights against the divine feminine. There’s the delight in poking fun at the opposing roles women must play in this culture as well: the public persona of the Madonna, and the private one of whore. “Chicago” the musical was bold in that it pulled the curtain back on the impossible position women have always been placed in, a position that never gives them recourse to anger, vengeance, or violence.

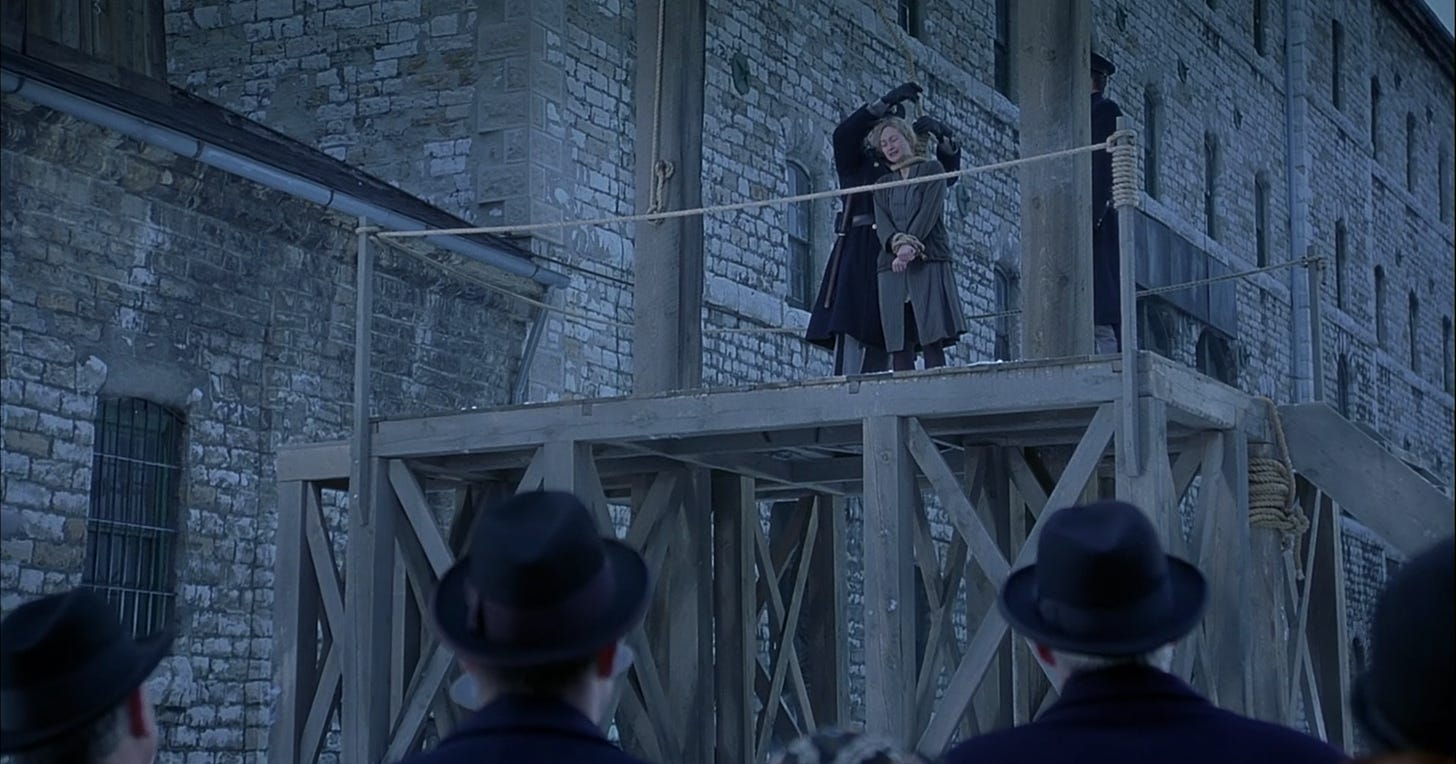

In reality, the 1920s were both a liberated and a stifling moment for women in America. The personae of the “jazz baby” and “party girl” were glamorized, but not quite accepted. Every movie from that time makes a point of both celebrating and punishing these characters, designating them as sinful aberrations from the feminine norm of wife and mother. Including the 1927 silent film Chicago, directed by Cecil B. DeMille and based on the original play by Maurine Dallas Watkins, who’d reported on two female “jazz killers” for the Chicago Tribune in 1924. Watkins adapted the story for the stage in 1926, and when DeMille made the movie a year later, he changed the play’s liberating ending—in which both women get off scot-free for the murders—into a moralistic one, putting Roxie Hart behind bars for good.

So you can imagine how, by 1975, audiences were ready for a new take on the legend of jazz killer Beulah Annan: one in which she not only gets away with it, but becomes a glamorous celebrity for plugging her boyfriend. The Fosse show transformed Watkins’ story into a celebration of female rage: in the musical, we’re shown a society full of people so desperate for women to play the part of the “reformed sinner” that they’ll even overlook murder to do it.

With all this in mind, I should have loved Chicago when I saw it. But I didn’t. All I could think about was how empty it was. It had all the ingredients I craved: show-stopping numbers, choreography up the wazoo, hilarious performances, and a sly revisionist history arc. But it left me cold. I knew I should have liked it—I was supposed to. My friends left the theater raving about it. I left wondering what was missing.

All these years later, I kind of get it. I wasn’t ready to love Chicago. I wasn’t ready to embrace that specific kind of emptiness it celebrates. I don’t think I was quite cynical enough to do that yet.

It takes a certain kind of cynicism to love and appreciate the work of Bob Fosse, which does something a little different with musicals than I was expecting as a teen. Traditionally, I’d known musicals to be one thing and one thing only: heightened technicolor dreamscapes filled with beautiful actors who were in love with each other. They were boy meets girl, they were aspirational, they were romantic. I didn’t realize that musicals could be so convincingly about romantic love’s opposite: not just hate, but the sweet coldness of revenge. These days, my favorite musicals (Sweeney Todd, Follies, Carousel, South Pacific) are about the disenfranchised, the misanthropic, and the dead. Back then, I just wanted a fantasy. This was a different kind of fantasy: a campy, funny, violent one. Chicago is a musical you grow into. It takes a little bit of growth, and a lot of bullshit, to get to a place where you can identify with Roxie Hart, a woman who shoots her boyfriend largely out of vanity, screaming “nobody walks out on me!”

The whole thing about Roxie Hart is that she’s not talented. In the words of her murdered boyfriend Fred Casely, she’s a “two-bit talent with skinny legs.” He says this by way of explaining why he didn’t—and never intended to—introduce her to his friend in vaudeville. That’s the way he got into her pants, by promising to get her closer to her dream of becoming a star. Once she finds out that he lied to her—and also that he thinks of her as talentless—Roxie pulls a gun from the dresser and shoots him at close range. “You lied to me,” she says. And again, she’s absolutely right. She gets her husband, the milquetoast Amos aka “Mr. Cellophane” to take the fall, but the cops see through it at once. Roxie lands in jail with her idol, the jazz singer Velma Kelly, and employs the celebrity lawyer Billy Flynn to take her case. Once he does, she becomes a sensation, a sweetheart of the press, an idol to the masses. She got famous in the only way that untalented people can: by becoming a brand. Roxie’s brand just happens to be that of murderess. And in 1927 Chicago, where they’ve never yet hung a woman, there’s nothing more glamorous than that.

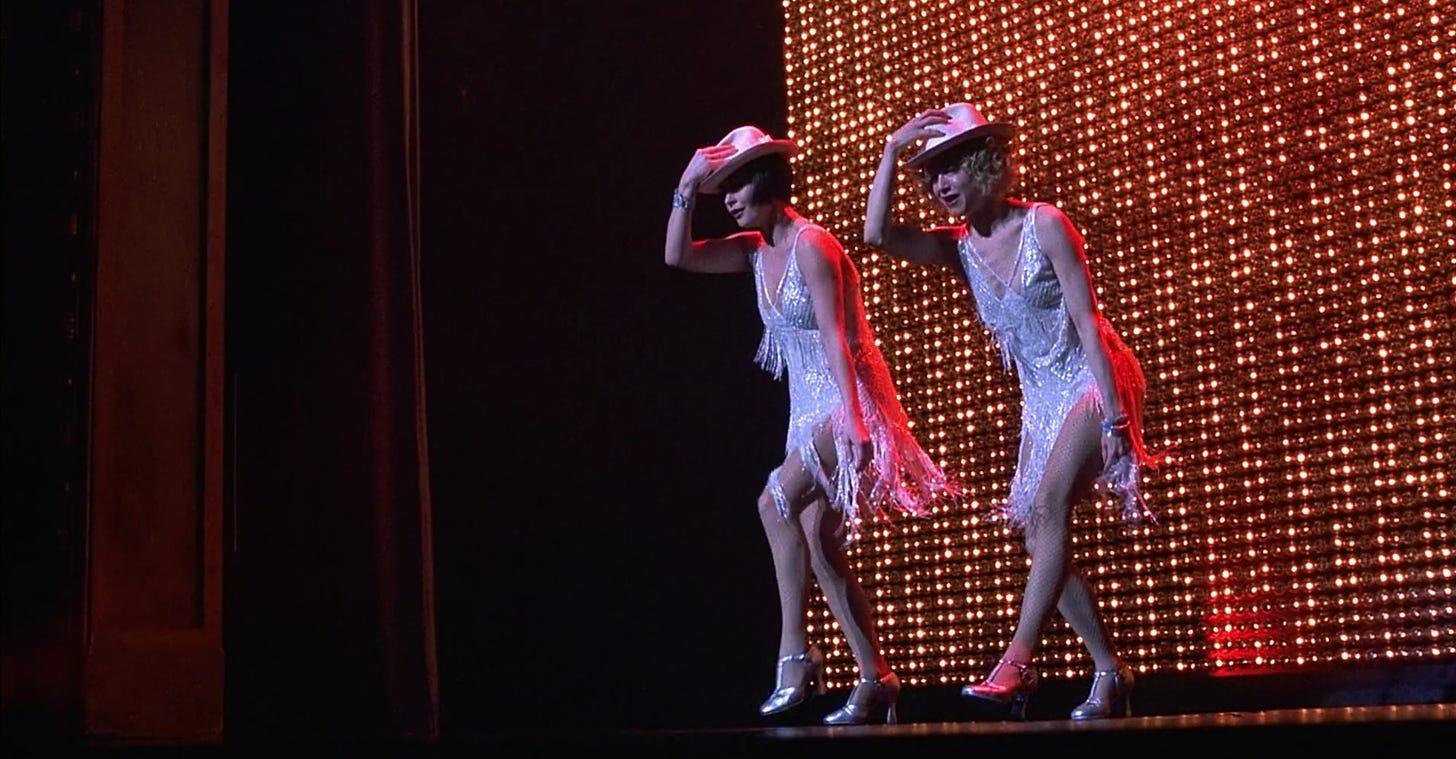

Of course, there’s a flip side to fame: it doesn’t last. Roxie soon learns that there will always be a new girl murderer, a new sensational story, a new scoop. She can’t hold onto the spotlight for long. She wins her trial and is released into a cold world that’s already forgotten her name, and it’s only by uniting for a double act with Velma Kelly—also a forgotten woman— that she can seize the spotlight once more. Kelly seeks her out, explaining that “one jazz killer act is nothing, but two…” Roxie almost turns her down. “It’ll never work,” she says. “‘Cuz I hate you.”

But Velma, ever the professional, isn’t deterred. “There’s only one business in the world,” she says, “where that’s no problem at all.”

It’s only by teaming up that the women can finally succeed in a world that’s still controlled by men. The end of Chicago is a beautiful embrace of the communal, of disenfranchised people finding power in numbers. You get the sense that it’s possible not simply to get away with murder, to get away with the ultimate female crime—equally as criminal in 2002 and 1975 as it was in 1926—of being completely yourself.

That’s what makes the politics of Chicago—both musical and movie—feel liberating. It’s not the kind of ending that makes you feel joyous and hopeful in the way a classic Hollywood musical might. But it does make you feel something. Gratified, justified, and delighted by the way it course-corrects, the way it seems to rewrite history itself. And that’s something I couldn’t really take in as a 13-year-old, before I had full access to the searing anger and pain of being betrayed, over and over again, by a society that would never celebrate me who I was.

There are plenty of things that make Chicago a better movie 20 years after the fact. There’s the way society has changed, for one thing (not enough, but it has changed) and the way that we’ve caught up to the divine feminine rage that the musical is mocking and celebrating. There are other things, too: the long-closeted Queen Latifah is finally out as gay (those in the know of course always knew) lending a new significance to her snarling rendition of the ode to sexual reciprocity “When You’re Good to Mama.” She wasn’t the only one: I came out, and my best friend at the time—the one I saw the movie with—has also since come out as bisexual. A lot has since been said that could not have been said in 2002, and a lot of what Chicago only hinted at then can be openly embraced now. We’re still a long way from truly celebrating and platforming female anger, and we still, of course, live in a society that hates women, gay people, and trans people. But in the 20 years that have passed, we’ve opened our eyes quite a bit to everything Chicago stands for. We’ve reclaimed icons like Britney Spears, Paris Hilton, and Lindsey Lohan, figures broken under the wheel of celebrity whom the culture encouraged us to mock 15, even 10 years ago. We’ve started to examine our hatred of and obsession with female sex symbols, our fear of women who embrace their sexuality, and our collective desire to see them punished. A reckoning has begun, and as always it’s never enough, but it’s a start, and a promise. Chicago—among so many other things—is so much a musical about time and its thorny passage. The trends that are doomed to expire, the celebrities that are fated to disappear, the ideas that feel socially important that are, in the grand scheme of things, destined to be replaced by others. “In 50 years or so,” Velma and Roxie sing in their final number, “It’s gonna change, you know.”

They were right, and they always will be.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox