But the bigger story has always been the less intimate one. For me, the historical narrative of the 90s is more personal than any of my memories from childhood. The mind is a magpie: it picks up shiny things, whether thematically related or not, and sticks them onto the same great clump, and this amalgamation of thoughts, films, pop songs, memories, abstract notions and half-remembered TV jingles, is what composes memory. It’s not straightforward and it’s not stratified. And the story of George, in my mind, is intertwined with the story of Howard Ashman.

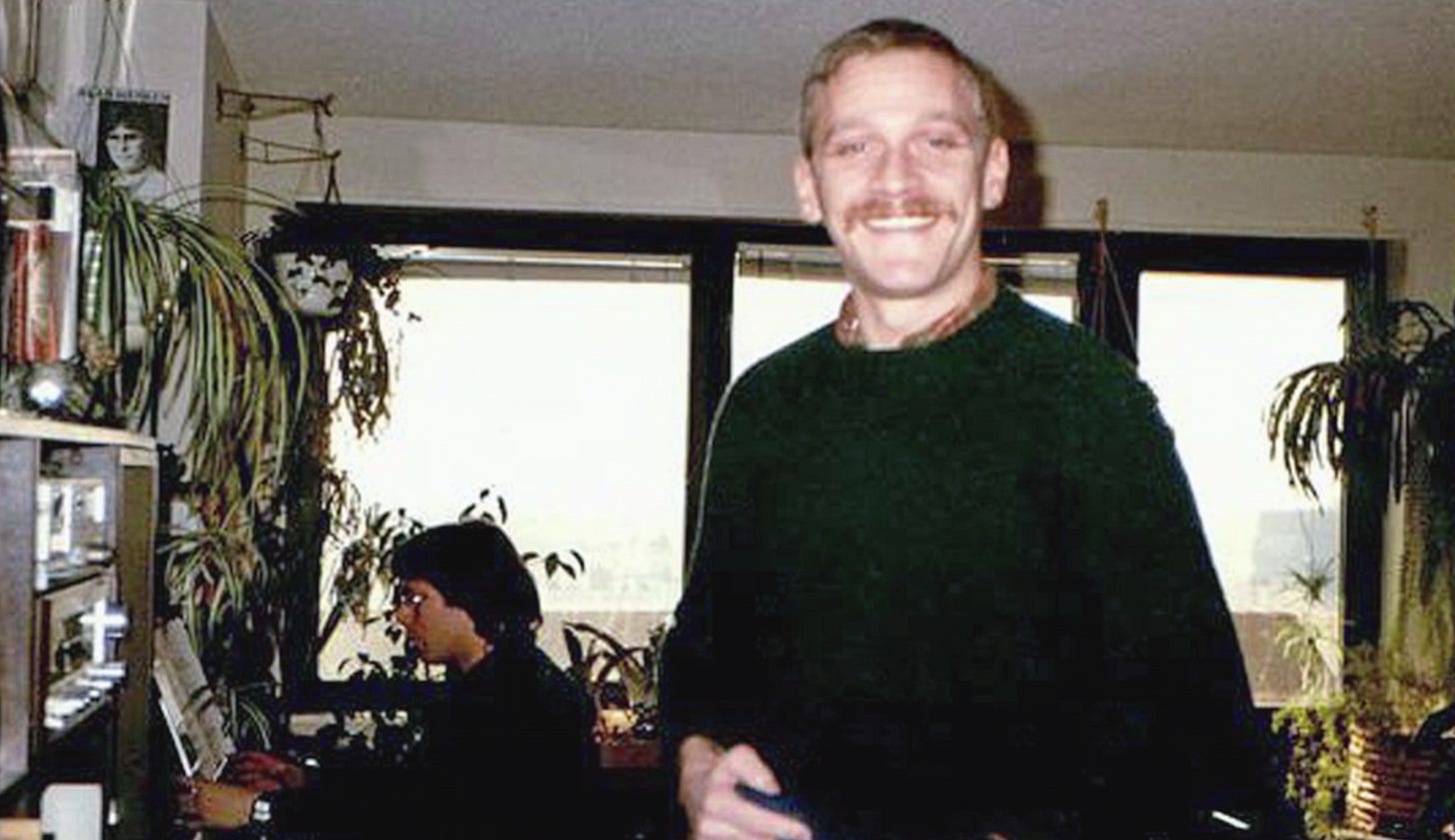

Ashman, for those of you who don’t know, was a Broadway lyricist best known for the musical “Little Shop of Horrors” and for his work on the Disney Renaissance films of the late 80s and early 90s. Ashman was also, to my mind, one of the most consequential figures of the American theater. He died on March 14, 1991 from complications of AIDS/HIV, before he was able to see a cut of his final work for Beauty and the Beast and Aladdin. A year previous, he’d won an Oscar for his work on The Little Mermaid. When Ashman received a posthumous award for Beast the next year, his partner, the architect Bill Lauch, accepted it for him. “This is the first Academy Award,” he included in the acceptance speech, “given to someone we’ve lost to AIDS.”

This is not why Ashman is the most consequential figure in American theater of the second half of 20th century, but it speaks to the many ways in which Ashman changed the firmament, a firmament that was screaming out for change.

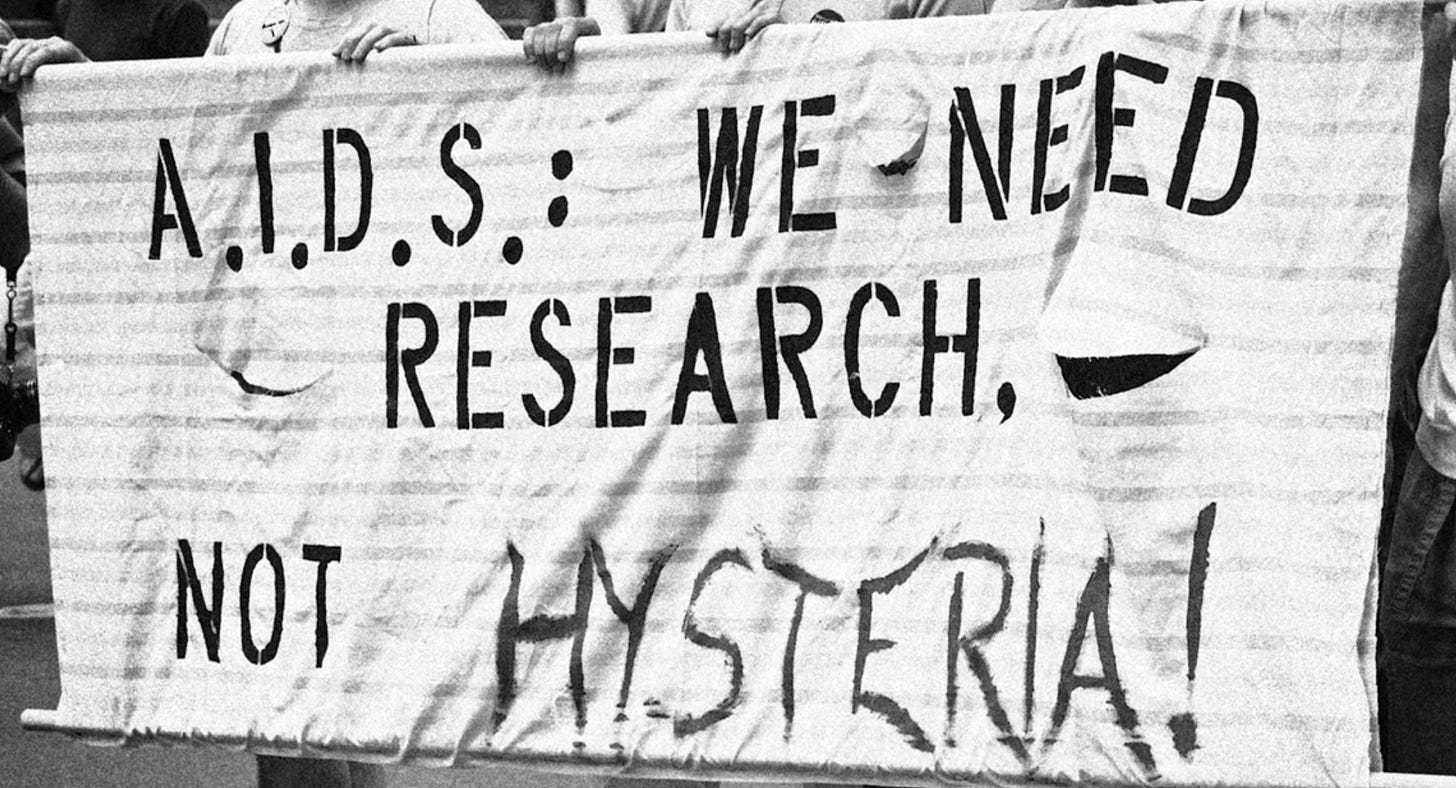

Disney producer Don Hahn, (Waking Sleeping Beauty, Hand Held) has been working on Howard, a documentary about Ashman, for years. This August, the film finally showed up Disney+. And despite being a straightforward doc, guilty of all the things that generally make me hate the documentary genre (one word: violins) it is a perfect encapsulation of what Ashman brought not just to the stage, the film world, and the world of music: It tells the entire story of the 1980s and 1990s in New York, unwittingly weaving together the personal tragedy of Howard Ashman’s story with the grander political tragedy of what the AIDS epidemic did to Broadway. In the oft-quoted (by me) words of Fran Lebowitz, one of the most crushing parts of the AIDS crisis wasn’t just the loss of so many incredible artists: it was the loss of an audience. The sophistication we used to associate with Broadway and New York theater has vanished in favor of franchise expansions and soulless tourist fare in part because of this. AIDS took out gay men of all kinds: artists, writers, architects, critics, dilettantes, laborers, sex workers, and addicts. We didn’t just lose them: we lost their taste, their sophistication, and their love of art. We lost their standards.

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

Howard Ashman had absurdly high standards: for himself and for everyone he worked with. He was deeply in love with his craft, despite describing the act of musical adaptation “an exercise in stupid.” Raised in Baltimore around the same time as another gay Baltimore icon, John Waters, the two men’s lives were destined to echo and reference each other until Ashman’s death. Both men were in love with performance, with actors, and with the outrageous. Some of Ashman’s earliest stage works were loving yet tongue-in-cheek adaptations of irreverent novels and fairy tales, notably his college production of “The Snow Queen” and a musical version of Kurt Vonnegut’s “God Bless You Mr. Rosewater.” The latter was a flop, panned by Walter Kerr for being messy and unfocused, but Ashman continued to hone his talent for giving famously unserious texts the musical treatment. “Little Shop of Horrors” was viewed by Ashman’s colleagues as a big mistake: who wants to see a musical based on some low-budget 50s movie? The success of “Horrors” was legendary, leading Ashman to his next project, a musical version of “Smile,” a 1975 satire about beauty pageant contestants. It, too, flopped hard, despite a passionate opening night audience.

The fact that Ashman found success in any medium is a small miracle. For an artist so committed to taking the depressing, the unfashionable, the resplendently obnoxious and setting it to music, it wouldn’t seem that Disney-level success was in the cards. Yet at some point between graduating from “hippie” college Goddard and establishing his own black box off-Broadway theater in 1977, Ashman was introduced to his future songwriting partner Alan Menken. After the failure of “Smile” in 1986, the newly-minted team was lured to L.A. by a persistent Jeffrey Katzenberg, the then-chairman of Disney with a bug up his ass about its flailing animation department. Katzenberg wanted Ashman to come and write songs for some new animated musical ideas. Ashman and Menken departed for Hollywood and found themselves shipped off to a backlot in Glendale, where the disgraced animation department currently resided, a sort of back-handed punishment for the box office humiliation of The Black Cauldron.

The team was disheartened, but still excited to work on their first project: an animated adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid.” It was an exciting prospect, especially for Ashman, who had grown up with Disney classics like Peter Pan and Cinderella. But Disney hadn’t made a good musical in a while. The old format from the 60s didn’t work anymore. Ashman quickly realized that while live-action films had left the old-fashioned pacing and plotting of the studio system behind, animation had aways to catch up. Disenchanted with the stage, he felt that animation might just be the last place where the traditional Broadway musical could still exist.

He was right, but he still had a fight ahead of him. During a development meeting for the film, Ashman described how the music and lyrics could be used to propel the story forward, as in a traditional Broadway musical. He told the animators about the need for an “I Want” song, where the leading lady sits down somewhere onstage and sings about what she wants, and from that moment, the audience loves her and is rooting for her. He gave Ariel her “want song” (“Part of Your World”) and gave Belle her “I want adventure in the great, wide somewhere” soliloquy. He turned Ursula from a derivative cartoon into a tantalizing villainess with clear motives and an unlikely inspiration: that of Divine, the John Waters stock character and famous Baltimore drag queen. He gave Ursula “Poor Unfortunate Souls” and he gave Sebastian the singing crab, “Under the Sea.” Instead of writing songs about nothing, as past Disney lyricists had done, Menken and Ashman threaded the Broadway structure into the animated musicals of the late 80s and early 90s, and it is for this reason that Disney enjoys its reputation today: It still uses the formula that Howard Ashman helped put in place. He gave Disney animation its first Oscar in decades, and Disney rewarded him by keeping him on for as long as they could, even after Ashman became too sick to work. It didn’t take long: during production for The Little Mermaid, Ashman began to notice white spots on his tongue. Thrush, he figured, but he was too scared to go to the doctor. He didn’t want to get an HIV test, because at the time, it could have lost him his health insurance along with his job. He opted instead for a T cell count test. It told him everything he needed to know.

From the time Howard Ashman was diagnosed as HIV positive to his death, he completed one film (Beauty and the Beast) and wrote half the songs for another (Aladdin.) He came to work when he could, even though everyone could see that he was rapidly losing weight, growing weak and irritable. No one knew why Howard came less and less to meetings, and because they didn’t know the reason, they assumed his Oscar had given him a big head. When the Beauty and the Beast production unit shipped itself from L.A. to Ashman’s home in upstate New York, animators were miffed, describing it as “bringing the mountain to Mohammed.” But Mohammed was dying, and only a few people understood why: Ashman’s partner, the architect Bill Lauch, and, later on, Alan Menken. Ashman waited until the last possible moment to tell anyone about his diagnosis. Instead, he worked until he couldn’t anymore. By the end, according to collaborators, they were “writing Prince Ali on his hospital bed” at St. Vincents in New York.

The producer Thomas Schumacher, interviewed for Howard, has perhaps the most impactful thing to say about Ashman’s work: “You can never take Beauty and the Beast away from the AIDS epidemic,” he says, pointing, among other things, to the film’s famous “Mob Song,” in which Gaston and the villagers, urged on by fear, plan to attack the Beast at his castle:

“We don’t like what we don’t/

Understand in fact it scares us/

And this monster is mysterious at least”

Director Don Hahn chooses, in the interest of fairness, I suppose, to follow this statement with a remark from Ashman’s sister, who survives him. She believes that Beauty and the Beast as an AIDS metaphor is “a bunch of hooey.” Instead, she claims, it was Ashman’s incredible empathy that led him to write songs about people with so many and various wants: a curious mermaid, an intellectual young woman trapped in a small town, someone who dreams of garbage disposals and chain-link fences. But to claim that Ashman never consciously wrote AIDS into his work is not to claim that AIDS never touched it. An artist with AIDS makes work about AIDS, whether explicitly or not. A gay artist working in the time of AIDS makes work about AIDS, whether they want to or not. An artist who wins an Oscar for his work and is unable to accept it because of AIDS is an artist whose work is intertwined with the disease itself. It is not our place to debate whether or not Howard Ashman’s work was influenced by AIDS: It simply was, and this takes away nothing. Neither does it add anything, necessarily.

I think there’s a bit of discomfort, or perhaps an ambivalence, about honoring a man whose gayness was not quiet, and yet whose contributions shaped an art form we like to think of as being “innocent.” But films for children are always made by adults, and adults bring their own complexity to these most universal of films. A film about a beast in self-imposed exile who feels himself impossible to love, a film about a man doomed to expire alone and in part because of loneliness, can be a children’s story and retain its maturity and depth. Children are not stupid; they understand complexity and are sometimes better equipped to deal with it than adults are. I think that having Howard Ashman be such an adult in a realm that never expected to tell stories about homosexuality created a strange kind of tension that explains, in part, why Ashman’s tragedy feels so deep to me. In my perfect world, people would be screaming Ashman’s name from the rooftops. In this same world, everyone watching Howard would have to take frequent breaks, as I did, just to get through it without getting so sad and angry that they want to break all the windows in their house. In my perfect world, people would not dismiss the work of someone who really did change the world for the better in ways that survive him simply because he worked for Disney. In my perfect world, people would not belittle an animated film for being animated, even before they know it’s about AIDS.

AIDS and Disney, as a cocktail, should not go down smoothly. But the beauty of the Disney establishment is that it exists outside of itself by now. At some point, Disney films weren’t about Mickey Mouse or Walt Disney or Bambi anymore. They became a formula: a way to tell hard stories about growing up to kids. That’s how I view the work of the Disney renaissance. They’re films that help kids grow up, just as Walt Disney always intended. But the Ashman trilogy is special: they’re are films about helping gay kids grow up. Ask any queer person who’s watched them. They’re made for us, by someone like us, and that’s a rare thing.

I’ll never get over the fact that Howard Ashman is dead. There are a lot of gay men who betrayed me by dying, most of them before I was even born. I’ve grown out of a lot of them, but Ashman becomes dearer to me with every passing year, with every new thing I learn about him. I will never stop watching those films, and he will never be dead to me.

Further Reading

Sarah Schulman, “Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America.”

Fran Lebowitz, “The Impact of AIDS on the Artistic Community”

INTO writer Juan Michael Porter II does great work over at TheBody.com, a resource for people living with HIV.