There didn’t used to be so many words. You were gay, queer, or a queen. And they all meant different things, but they all put you in largely the same category: a person society hates.

It’s only now that the words have become important. In the past, there were only codes.

Frank Simon’s 1968 documentary The Queen is a portrait of a community without a name. It follows drag icon (and later, trans activist) Flawless Sabrina as she organizes and emcees the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Contest. She has a protege, Rachel Harlow, and more than a few enemies. But she is the leader of this community of misfits, and her pageant places trans women, drag queens, and gay cis men under one roof as they are judged on a five-point scale. Five points for walk, five for talk, five for bathing suits, and ten for overall “beauty.”

From the very start, it’s not clear what the director thinks this story is about. Is it about Sabrina herself, a 24-year-old drag queen who, the same year as The Queen was being filmed, moved into her legendary apartment which would become a salon that saw the likes of Truman Capote, Rudolph Nureyev, Andy Warhol, and Michelle Obama?* Is it about the queens themselves, young gay men, mostly, who dress as men when they are out of drag. Or is it about the few others who hang on the sidelines, like Sabrina’s protege Rachel Harlow, a 19-year-old AMAB queen who looks, talks, and dresses like a tomboy out of drag?

It’s about all these people, and none of them. More than anything, it’s about the situation the queens are in. Unable to distinguish between different types of queerness inside of an era that painted one single scarlet “Q” on your forehead no matter where you fell on the spectrum of gender and sexuality, the queens bond and fight, they express differences of opinion, they revel in their beauty and call out each others’ ugliness. Some would like to have what they refer to as “sex change” surgeries, and some would not. Some want to serve in the military. All of them are hurt, and they relay this to each other and the camera. One queen tells a story where a man walked up to her and said, “you’re not really a woman, are you?” Another expresses confusion about the overlap between sexuality and gender. “Most queens are gay men,” says one of the contestants, explaining that the men at home don’t want a beautiful woman coming to bed. “They don’t want a girl,” he says, “they want a boy.”

This is a very far cry from what we’re used to in the 21st century. We have out transgender politicians, actors, writers, and filmmakers now. Drag is a part of the culture in ways no one could have predicted (the Broadway musical of “Priscilla, Queen of the Desert” comes to mind.) Drag Race has had so many seasons I can’t even count them anymore. Drag is still beautiful, but it’s corporate. It’s a franchise. In the words of Sabrina herself in The Queen, “it’s commercial.”

But when you watch these queens putting on their makeup, taking pains to choose the right clip-on earrings, using the same shitty makeup tools and brushes they’ve had probably since they were teenagers, you realize that drag used to be something different. An actual rebellion. You had to lose something to perform it. Maybe your personhood in the eyes of the larger world. Maybe your pride, if you lost too many times. Drag used to cost something. Now it’s a fun detail on someone’s bachelorette party itinerary.

Sour grapes, sure. But you listen to a young man who looks exactly like Grady Sutton sing the most perfect, heartbreaking cover of “101 Pounds of Fun” from South Pacific and tell me you don’t feel it. The sadness.

Tell me you don’t get how hard it is that people work for something in ways that cost them everything, only to have that thing become nauseatingly mainstreamed 50 years on. And it’s not the mainstream part that’s sad: it’s the fact that drag has become so much a part of the culture that its power is rendered meaningless.

There’s a lot of sorrow in representation, and people don’t talk about this. Rightfully so: it’s a bummer! But it’s a very peculiar thing to feel excited about the existence of artifacts like this mixed with the deep sadness invoked by the kind of lives they had to live. Even if they experienced joy, which many queens do in this movie, it goes hand in hand with the depression of knowing that once the queens left the stage, their lives were hard and painful. There was only one place where they could feel real, and it was onstage. But not just any stage—a specific stage that had to be fought for, protected, and maintained at all costs.

According to the New York Times obituary, Sabrina “organized [their] first show in 1959 and produced many thereafter, working surreptitiously to avoid the morality police and sometimes the actual police, since some cities and states still had laws against cross-dressing.”

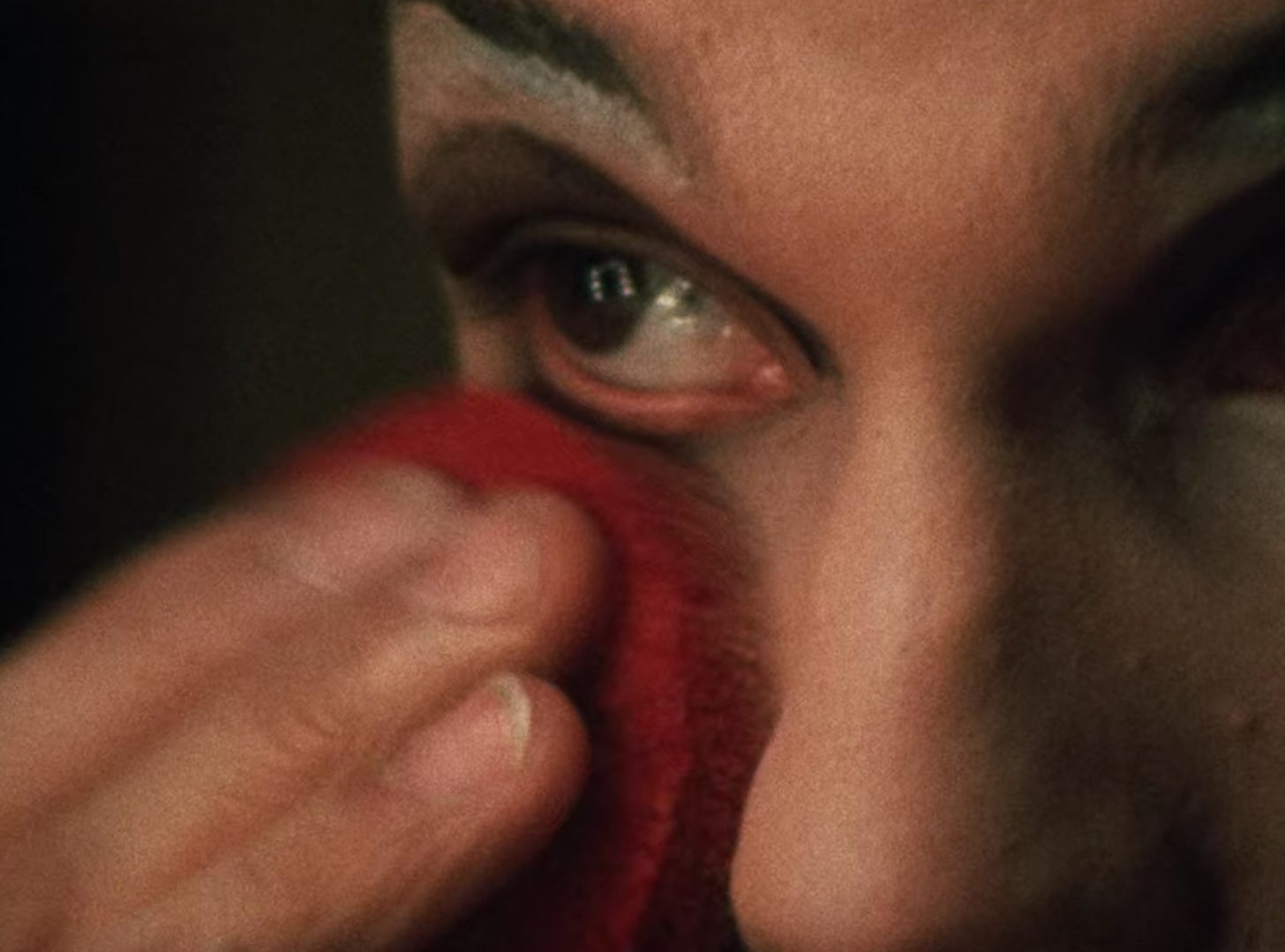

The people who did it back then remember how hard it was. What an effort of will it must have been to simply perform on a stage somewhere, for other people like you. Back then, the prize wasn’t winning. It was being able to do it. “You ask a queen what her name was before,” Sabrina explains early on, while applying powder to her under-eye area. “And they say, ‘there is no before.’”

To be seen, for a brief, flickering moment, as the person you are. That was the prize: A crown with no value, except to us.

*Such luminaries would continue to stop by for 40 years until Sabrina’s death in 2017.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox