I’ve shown the movie The Man Who Came to Dinner to several people in my life, and each time I expect them to understand what the hell is going on without any commentary or clarification from me. I always act shocked when the person I’m watching it with comes away with a sense of broad confusion, not unmixed with admiration. Then I have to describe the play—and movie—the best way I can, and I usually say something along these lines:

“It’s a play that asks, what if the most obnoxious man in New York got stranded in a straight-edge Midwestern couple’s manse in Buttf*ck, Iowa, and invited all his gay and Jewish showbusiness friends to join him, slowly driving the Midwestern couple insane through sheer force of personality?”

Of course, there’s a lot more to it than that. The Man Who Came to Dinner, both play and movie, concern one Sheridan Whiteside, an on-air intellectual known for his Sunday night broadcasts. His is inexplicably beloved by housewives across the country, despite being as New York as it gets. And New York, in the case of Whiteside, means something very specific: pretentious, literary, impatient, a bearer of extremely petty high standards in everything. He is a person who surrounds himself with Hollywood glamour girls, great ladies of the New York stage, darlings of the Algonquin Round Table, and literary vivants. He is also, without ever showing sexual interest in men or seeming to have any discernable sexuality, extremely gay-coded. He is, in a word, Alexander Woollcott.

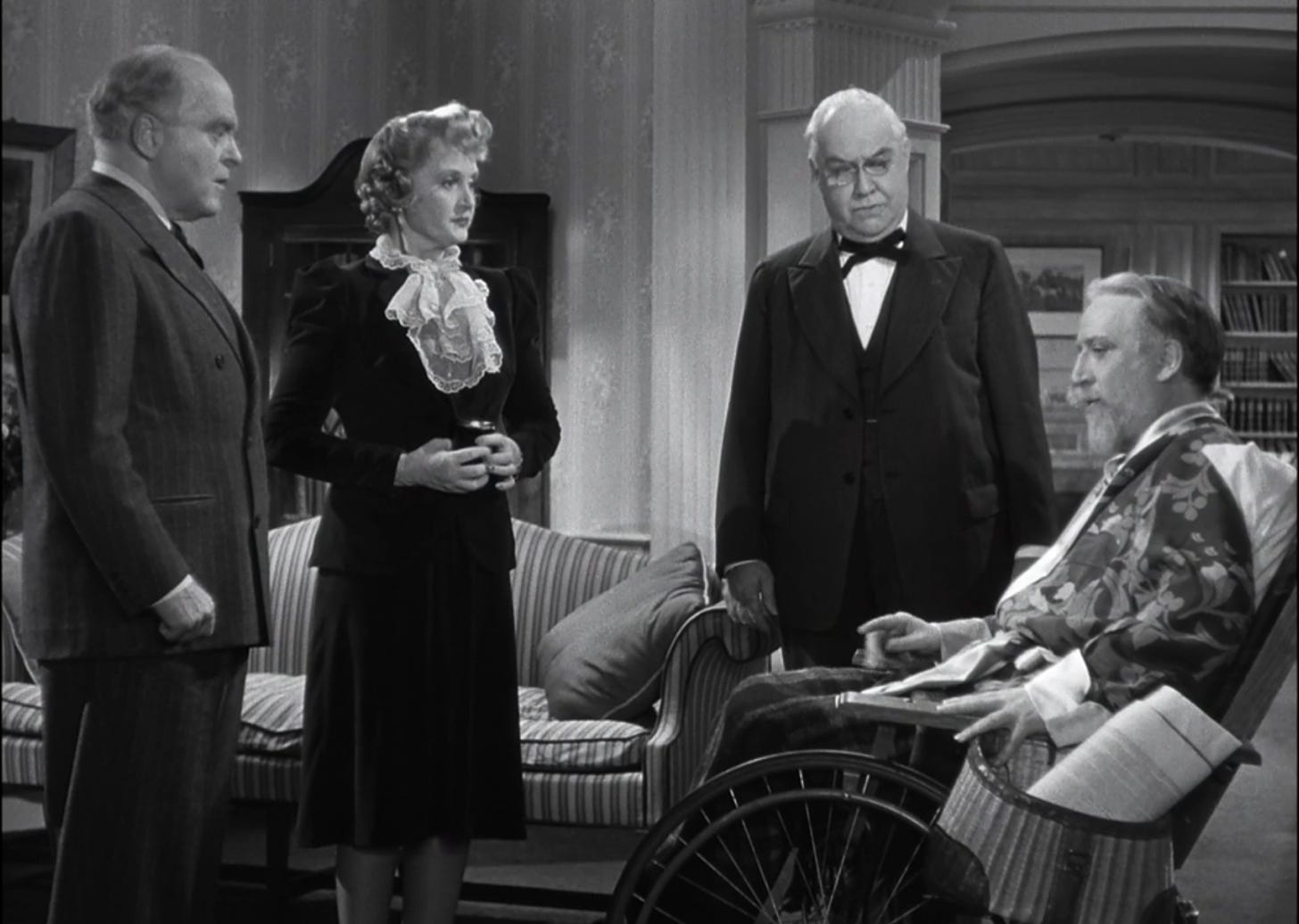

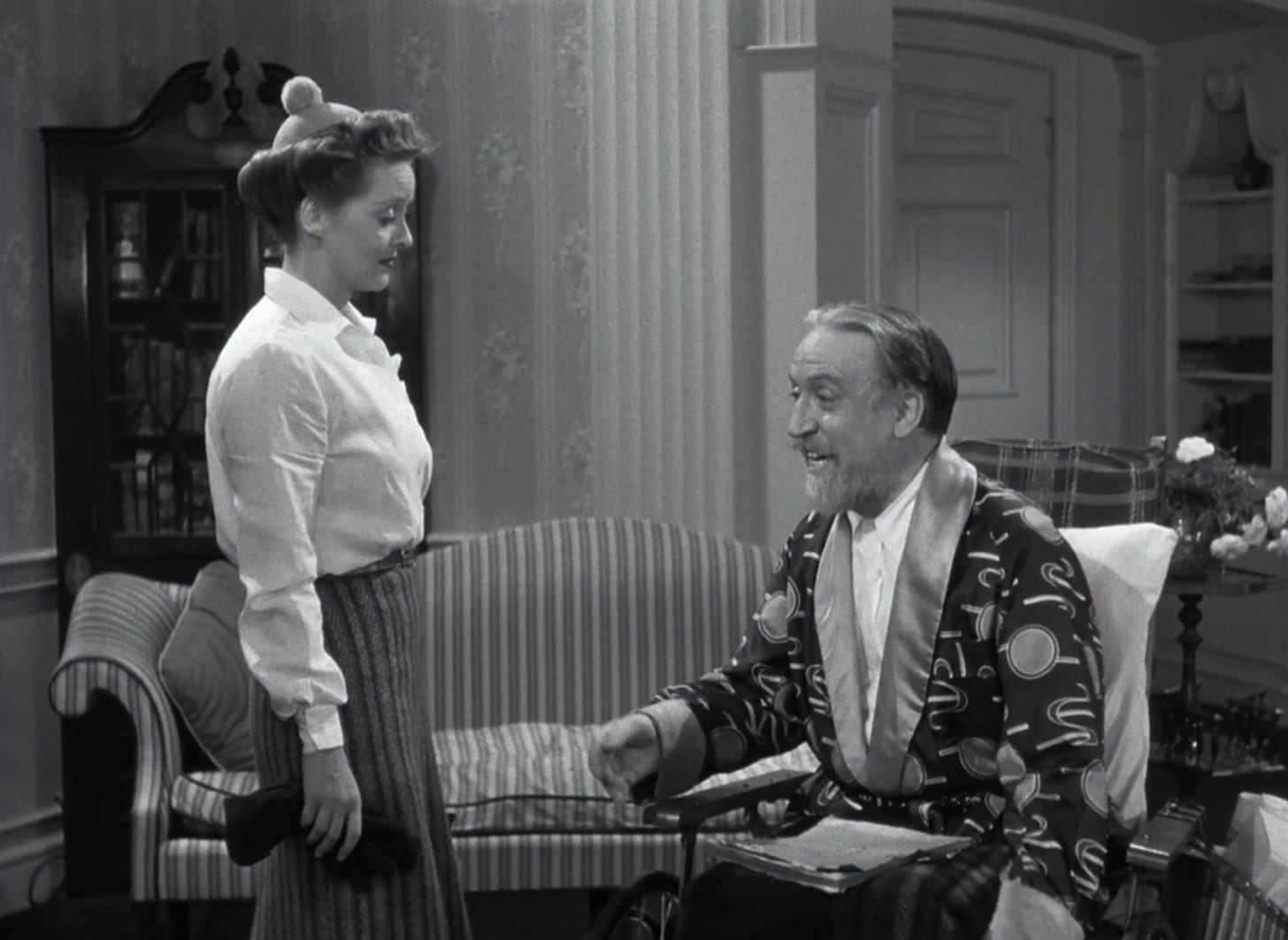

The play’s authors, Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman, were quite open about basing its central character on their friend Woollcott, the 20th-century literary critic known for his passionate friendships with Noel Coward, Dorothy Parker, Gertrude Lawrence, and Harpo Marx. Woollcott even eventually played the role onstage as the authors intended, but for the film, he was passed over, rightly, for a much straighter-seeming gay man, the veteran crank character actor Monty Wooley. The role of his secretary Maggie Cutler was given to Bette Davis, while the role based on Gertrude Lawrence went to WB “Oomph girl”1 Ann Sheridan. The result is a sparkling, but incredibly dated affair that remains one of my favorite Christmas movies perhaps because of the frantic atmosphere it manages to capture.

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox

All the things that should make the movie stagey and unbearable (the limited camera movement, the constant entering and exiting of prominent characters into the same living room, the rapid-fire dialogue) manage to make it a peculiarly stressful kind of Christmas movie2. Not only does it get that manic energy right, it manages to make it both disconcerting and weirdly cozy: it captures that feeling of living in a place where the rooms are always full of strangers, buzzing with life, full of conversations you’ll never manage to really get a grasp on. Everyone in this movie is grasping and scheming and living out their little private New York dramas—from the comfort of some asshole’s living room in Mesalia, Ohio. And isn’t that just the perfect summary of what it feels like to be gay and arriving home for Christmas, especially if “home,” for you, happens to exist in one of these small towns that we spend the rest of the year fearing, hating, making cruel jokes about, and looking down on?

The plot, in short: Sheridan Whiteside comes to Mesalia, Ohio, during a speaking tour. On a visit to the very proper Stanley residence, he slips on the steps and falls, and must use a wheelchair for about a month, until he makes a full recovery. In that time, he makes it his mission to terrorize the household: conducting his business out of it, doing his radio broadcasts from it, inviting groups of incarcerated people and Chinese businessmen to dine at the table that does not belong to him. He takes up space, grandly, and throws a wrench specifically into the Stanleys’ boring Midwestern plans for their children, who were already aching to rebel before he got there. He breaks up his secretary’s romance with a local (“corn-fed”) playwright, then brings them back together again. He orders cases of antarctic penguins to the Stanley house. In effect, he holds court in the gayest possible fashion, refusing for even an instant to be anything but himself dialed up to the full 11. And it’s Christmas, the time during which gay people are famously told to shut the fuck up and stop making everyone uncomfortable in favor of a quiet, nonconfrontational evening.

It is a gay fantasy of wreaking havoc on middle America, and it takes a gay, possibly asexual, critic as its primary inspiration.

Even without the Woollcott aspect, I think this movie would have no trouble appealing to me—the script is 2/3 baroque insults (“You Simpering Sappho”, “You Flea-Bitten Cleopatra”) 1/3 soda water, and it follows the traditional style of any Marx Brothers comedy, in which an extremely buttoned up world, usually represented by Margaret Dumont, is thrown into utter chaos by the arrival of four ill-mannered Jews. And make no mistake, it is the gay part, and the Jewish part3, that’s really at the heart of why the film remains interesting. We know New York today as a place defined more by privilege and wealth than by esoteric literary references and caustic wit. In the 1920s, when Woollcott was at the top of his game, and well into the 1940s, it was seen not only as a place where “intelligent” theater could thrive, but a place in which people could live who had no other earthly place to call home in this country. The fags, and the Jews, and the people who knew what the name “Cornell” meant without further clarification. This is their world, and it has come to Mesalia.

In real life, Woollcott did surround himself with difficult New York types. His friendship with Harpo Marx—which some speculate to have been an unrequited romance on Woollcott’s part—carried on far into Marx’s marriage to a woman, and is evidenced by years of oddly sweet letters back and forth. Woollcott rubbed elbows with other literary oddballs like Dorothy Parker and Oscar Levant, and famously said of reading Proust that it was like “bathing in someone else’s dirty bathwater.”

He had strong opinions, and was defined by them. His personal life, like most queer people of the time, was the subject of wide speculation. Some claimed that a case of mumps from childhood left Woollcott “impotent,” while other sources claim it resulted in a “hormonal imbalance” that caused him to be unable, or perhaps simply uninterested in, engaging in sexual acts. He was a large man who made no excuses for the amount of space he took up. His influence was extraordinary: but, being so much a man of his time, it’s no surprise that his name inspires a kind of glazing over in the eyes of listeners today. He was a gossip, a critic, a writer and editor of some of the earliest “Shouts and Murmurs” pieces in the New Yorker’s history. Of course we don’t remember him: he didn’t leave us anything to remember him by.

I often think of Woollcott in the context of my own career. What happens to people who spend their lives putting out small pieces of work: reviews, essays, of-the-moment joke writings, hot takes. Do we survive past the small window of our time on earth? Does our work speak to anyone besides archivists and people like me, dust-covered assholes with nothing better to do than comb through the annals of history looking for the gay weirdos the culture has seen fit to discard? I guess, as with everything, only time will tell.

And if we’re not remembered, I guess that’s kind of fine. There are all kinds of writers—all kinds of gay people, too. Not just the kind that can speak for and to and also beyond the time in which they live, but the people who are choked and bound by their time’s preoccupations, its struggles, its minor annoyances. There are arbiters of taste who exist to be snobs, and there are others with a genuine urge to broaden the world they live in through a love of art, of weird exhibits, setpieces, long-gone gestures and phrases. There are critics, and then there are memory critics, infusing everything they do with a touch of perhaps obnoxious, unneeded context. We’re a little bit much at times, a little too gay and passionate and weird. But we mean well.

And the thing is, we can’t help it, the Sheridan Whitesides of the world. We have to be ourselves at all times, forever, lest the ceiling of the world fall down upon us.♦