Jeffrey is an ecstatic movie, just as I remembered it. It moves, it spits, it fucks, it fantasizes, and it is unafraid to be passionate. And it’s hilarious. When I described this film as an AIDS comedy, I was being quite literal. This is one of the few films I can remember that takes a comic approach toward the epidemic. It’s bold, it’s fourth-wall-breaking, and it works. Because the thing about AIDS is that we know it was a tragedy. We know it was—is—horrible. It was so horrible, we feel bad even laughing about it now in some of the lighter moments of Pose and It’s a Sin. But Jeffrey was unafraid to laugh in the face of death, panic, uncertainty, and AZT reminders. And it came out in 1995.

I can’t talk about why Jeffrey is so great without talking about the cast. This is a small-budget film with the look of a big-budget one, thanks to shrewdly-placed cameos by gay icons like Christine Baranski (she’s so young!) Nathan Lane (as a horny, musical-loving priest!) Sigourney Weaver (as a bitchy self-help guru) and Victor Garber (a sex addict!) Also: Kathy Najimi, Olympia Dukakis, and Bryan Batt, which some of you may know as Salvatore Romano from Mad Men. He’s a Cats dancer and HIV-positive boyfriend to Sterling, played by Patrick Stewart, who has perhaps never been better.

Based on his play of the same name (a play that theaters at first refused to run because of its subject matter) Jeffrey is probably the last (only?) wonderful thing Paul Rudnick wrote since becoming desperately lazy at the New Yorker. It’s so dynamic, to the point where you feel like New York City is truly a place created by—and for–gay men. It’s a story in which gay sensibilities are not tragic, but personified. Nothing is polemical, and Patrick Stewart wears a pink beret.

Related:

My Favorite Gay Character of the Year is a Total Sociopath

“Rain Dogs” is, at heart, a story of chosen family. But it doesn’t sidestep the aspects of chosen family that can be just as abusive as biological family

The plot you ask? It’s this: Jeffrey (Steven Weber) is a pushing-30 gay man living in New York in the gay 90s. He’s paranoid about getting a positive HIV diagnosis. He used to love having sex, now he’s just scared. When we meet Jeffrey, he is at the start of a journey to remain celibate. Romance, of course—and general horniness—keep getting in the way. It’s a sex comedy by way of abstinence: think 40 Days and 40 Nights combined with the politics of Lysistrata and the manic energy of Love’s Labour’s Lost. But make it campy.

The thing about Jeffrey is that it isn’t just campy. It comes from a real place of pain and fear, and it feels like a document of not just a moment in history, but a moment in the history of ways to feel about sex. Straight society has historically feared sex for its ability to spread disease, bring life into the world, and enforce shitty power dynamics between men and women. But to read a book like Edmund White’s “States of Desire”, published in 1980, is to learn about the world of gay men before the AIDS epidemic—a world in which sex, all kinds, is celebrated, hungered after, and centralized in the culture. It was the last time, really, gay men could think about sex that way: as a carefree exercise that brings you into contact with the only people who actually understand you. Or are like you.

Obviously, that changed quickly the year after, in 1981, when a mysterious virus had started to creep into the public eye. By 1995, the year Jeffrey came out, there was ACT UP, Clinton’s PACHA Council, and 31,500,000 deaths on record. So yeah. People were freaking out about sex, understandably.

We know what happened with sex—it got safer for some people, or it didn’t, or people abstained altogether, as Jeffrey tries to do. What we don’t know is what happened to romance. People lost their partners, entire power couples were swallowed up by the void. But what happened to romantic yearning?

That’s the question Jeffrey attempts to answer. He tries to have safe sex. He calls his parents, only to get in between one of their phone sex sessions. He keeps running away from Steve (Michael T. Weiss) the cute top that’s been chasing him all over the city. He is not so much afraid of sexually-transmitted diseases, but the intimacy that might occur between him and someone who’s positive. His best friend Sterling (Patrick Stewart) is less worried about the whole thing, possibly because his boyfriend Darius (Bryan Batt) is already positive. How can you just go about your life, Jeffrey is always asking Sterling, when you know your lover could die at any moment? Sterling shrugs it off until the last moment. And in that last moment, of course, Darius dies. Because this is a movie about AIDS.

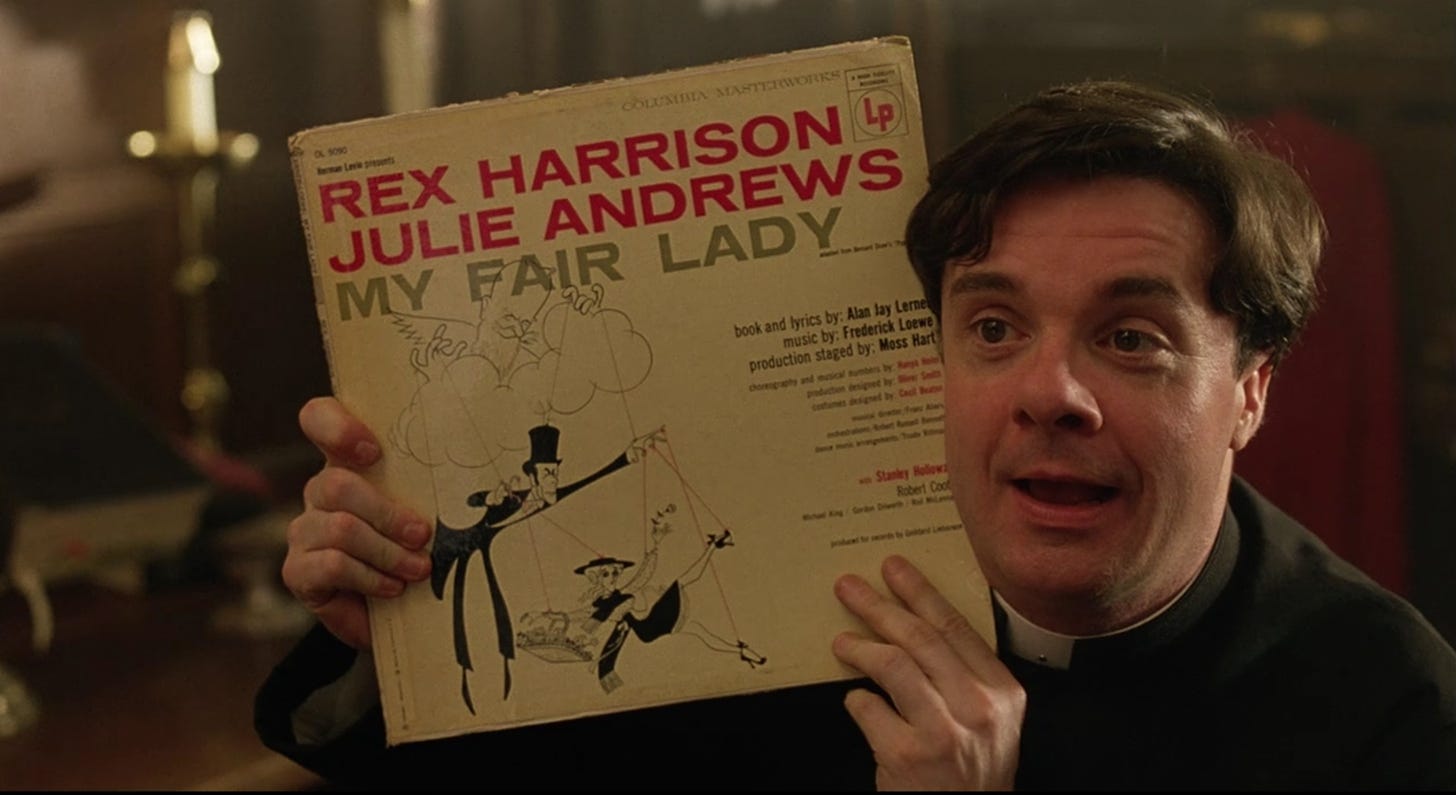

But it’s not that kind of a movie about AIDS. It’s not “Angels in America,” and it’s not the kind of gay martyr story you’d expected from this era, even in work created by gay men. It’s too lively for that. This is a movie where Olympia Dukakis shows out in full feather at a Pride parade to support her adult trans daughter. A movie where Jeffrey calls his parents to discuss his romantic woes only to be caught in the middle of one of their phone sex sessions. Where Jeffrey goes to church to find answers, only to have his ass grabbed by the priest (Nathan Lane) who proceeds to tell him that God is a Columbia recording artist.

“Your parents had the record, remember? And George Bernhard Shaw manipulating the strings of Julie Andrews and Rex Harrison? You thought it was God.”

Unsatisfied with this explanation, Jeffrey retreats, causing the priest to shout after him. “I’m sorry I couldn’t give you the meaning of life in two seconds.” He then offers to tell Jeffrey what God really is.

“Have you ever been to a picnic,” he asks, “and somebody tosses a balloon up in the air, and everybody tosses it around? And it’s always just about to touch the ground. But someone always gets there just in time to tap it back up. That balloon…that’s God.”

It’s not just the beauty of a world in which a seeking, questioning young man is met with wild, wonderful queer characters to act as his Virgils in the underworld of the AIDS epidemic. It’s the beauty of each of those characters and how they honor life, even in the midst of death. It’s also true to life in the way it moves. We see Darius faint at the Opera. The next scene, it’s New York pride, and he’s up again, talking about how wonderful it is to be around everyone, describing the community feeling ecstatically as “the opposite of AIDS.” The next time we see him, he’s dead. “He passed away 30 minutes ago,” Sterling tells Jeffrey in the hospital waiting room. It’s that shock that gets you. You thought he was going to be fine. But it’s up and down, always. Disease and death do not honor the petty narrative structure of our dramas, or even our best comedies.

That’s Jeffrey’s best quality, I think. It honors it’s own vision of reality. It is an absurdist film that is also a documentary of what it felt to be living, as a gay man, in New York, in 1995. Jeffrey is a film that bends the world we know to fit a gay sensibility. And for me, there’s nothing happier or more life-affirming than that. Even if it is about a plague.♦

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox