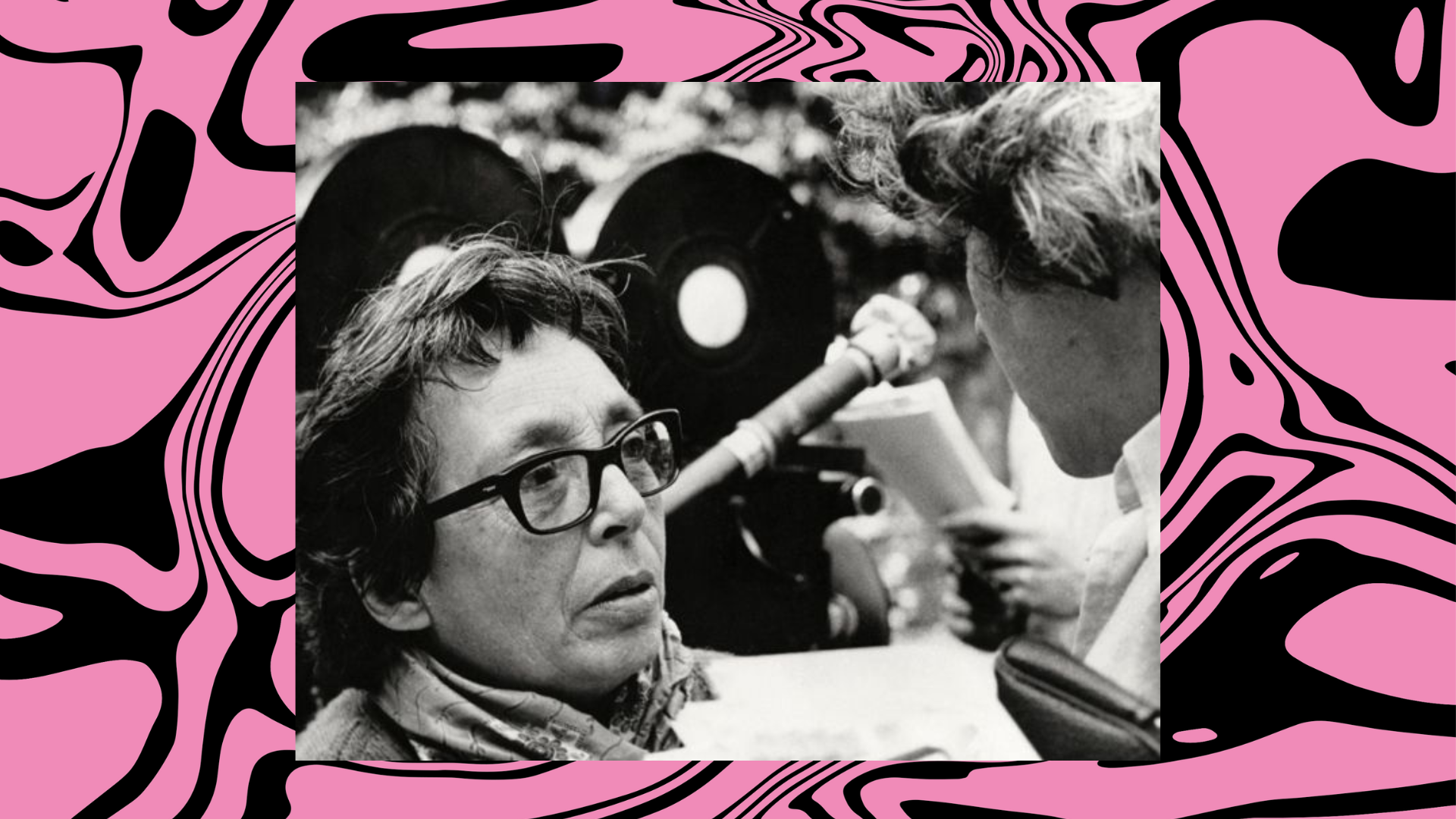

A duet of Marguerite Duras’ films released last month by The Criterion Collection celebrates the post-War director and her remarkably singular point of view. India Song and Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977) both showcase an artist moving at her own pace while still posing similar feminist questions as her contemporaries like Chantal Akerman and Agnes Varda, especially women’s agency under capitalism and how to create an alternative cinematic sensibility that was separate from masculinist mainstream cinema.

Best known for writing the script for Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour, by the time she made these films, Duras was in her early sixties with a well-established lyricism akin to something like “poetic realism.” Firmly in control of her talents, Duras took to film to maintain artistic direction in adaptations of her work. A mix of metaphor, quotation, poetry, and dialogue, the words in a Duras film tell a story, yes, but they primarily work to bring out more latent possibilities. In the essay by Ivone Margulies included in the set, these possibilities are the “internal shadow” brought about by waves of word images. As the “image-sound separation” compounds on each other, the words and “dialogue” off screen being more cluttered than the vacant visual composition, we are encouraged to “see less [and] listen more.”

Related:

What Doris Wishman Got Right (and Wrong) in the Transploitation Classic “Let Me Die a Woman”

Wishman’s prolific career spanned decades, as she turned out low-budget, boundary-pushing exploitation films that addressed subject matter Hollywood would rarely touch.

Both India Song and Baxter, Vera Baxter use elegantly sparse visual compositions in contrast to the ornate “narrations” happening off-screen. India Song fully embraces this technique to tell its tale of decaying colonialism. At the end of India’s occupation by Western forces, Anne-Marie Stretter (Delphine Seyrig) is adrift in her ennui. Just as the empire is crumbling, so is her marriage. To pass the time and attempt to stave off suicidal boredom, she takes on a series of lovers, much to the displeasure and madness of her husband. Told through off-screen dialogue about and by the goings on in the governmental villa, it’s as if we’re watching a Pepper’s Ghost of postcolonialism — the regiments of empire waltzing in place, a faint image of their former selves.

Vera Baxter (Caludine Gabay) languishes in a similarly empty villa. Sent there by her husband, she’s tired of everything — his affairs and her own, of the endless waiting. She’s visited by her lover (Gerard Depardieu), her husband’s mistress (Nathalie Nell), and a stranger (Delphine Seyrig) drawn to her by the sound of her name, Baxter, Vera Baxter. Each apprehensive apparition tells us more about Vera and her world. They must bring the outside to her because Vera is trapped, or perhaps already gone.

Duras as a director excels at stillness. She relishes it. And while her resting shots and monotonous monologues at times feel punishing, they’re not without purpose. These films are proto-“slow cinema,” each deliberately working to suspend normal sensations of time and duration. India Song uses crashing recitations and still-life compositions to cede any sense of “progress.” In Baxter, Vera Baxter, the folk song endlessly looping in the background, becomes frustrated and too aware of how much we rely on sound/scores to bring us to a “point.”

Like her feminist contemporaries, Duras was keenly aware of how white masculinist mainstream cinema was supported by speed and notions of progress. Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is perhaps the most oft-cited example. But Chantal Akerman’s film concludes in a way Duras’ films do not. But it’s not a coincidence that both Akerman and Duras employed Delphine Seyrig, one of the definitive actresses of Second Wave Feminism. She understands the power of silence and stillness and how to utilize them. Her ability to transmit vacancy made her one of the premiere talents for telling stories about the bifurcation of women’s lives and spirits. In India Song, she is a woman whose body barely contains what’s left of her spirit, while in her appearance as the stranger in Baxter, Vera Baxter allows her to be remote and attuned, like a satellite in orbit. Known for her activism and acting, Seyrig carried intent into her bones.

It’s as if we’re watching a Pepper’s Ghost of postcolonialism — the regiments of empire waltzing in place, a faint image of their former selves.

BL Panther

Both India Song and Baxter, Vera Baxter control strong political intent that keeps the films charged, despite their lethargy. The ennui that Duras expertly replicates is a white existentialist one directly linked to the decline in colonial power. Still, it is not in itself a critique of the colonial structure. We are still always trapped with the white fragility, one that cannot survive a loss of dominance.

The films in this collection are highly metonymic. Duras fills them with small objects, details, and symbols to suggest the whole world outside. Just as a camp lens recalls an entire history of production, of werk, Duras’ vision uses poetic visual moments that bring in complete histories, personal and political. Her films startle us awake to new possibilities of cinema and experiencing the world.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox