I love Christmas movies probably more than any Jew you’ve ever met, with the exception of my mother. In my family, Christmas is in our DNA. We watch White Christmas and Remember the Night and It’s a Wonderful Life every year without fail, and we know the words by heart.

I love everything about Christmas: The religious stuff, the secular stuff, the old songs, the old movies, the Bing Crosby and Currier & Ives of it all. But my favorite Christmas movie is not White Christmas, or It’s a Wonderful Life, or even Christmas in Connecticut. It’s A Midwinter’s Tale, a film Kenneth Branagh made somewhat early in his career, back when he was still trying to be Woody Allen.

In fact, you could say that A Midwinter’s Tale is the greatest Woody Allen movie never made. It’s a very small film, shot in black and white and almost completely in long shot. It stars some of the best actors you’ve never heard of. And it gets to the heart, better than any movie I can think of, of what the secular concept of Christmas actually means. Rather, what it should mean.

A Midwinter’s Tale, at its heart, is about how art can create a family where there wasn’t one before. It’s about the kind of all-consuming passion that eats you up when you really love a work of art, and how that love can extend toward and enfold others inside it. It’s a film where characters truly, deeply love each other without being in love with each other. More than anything, it’s a movie where people give to each other. They give the gift of their true selves to one another, warts and all.

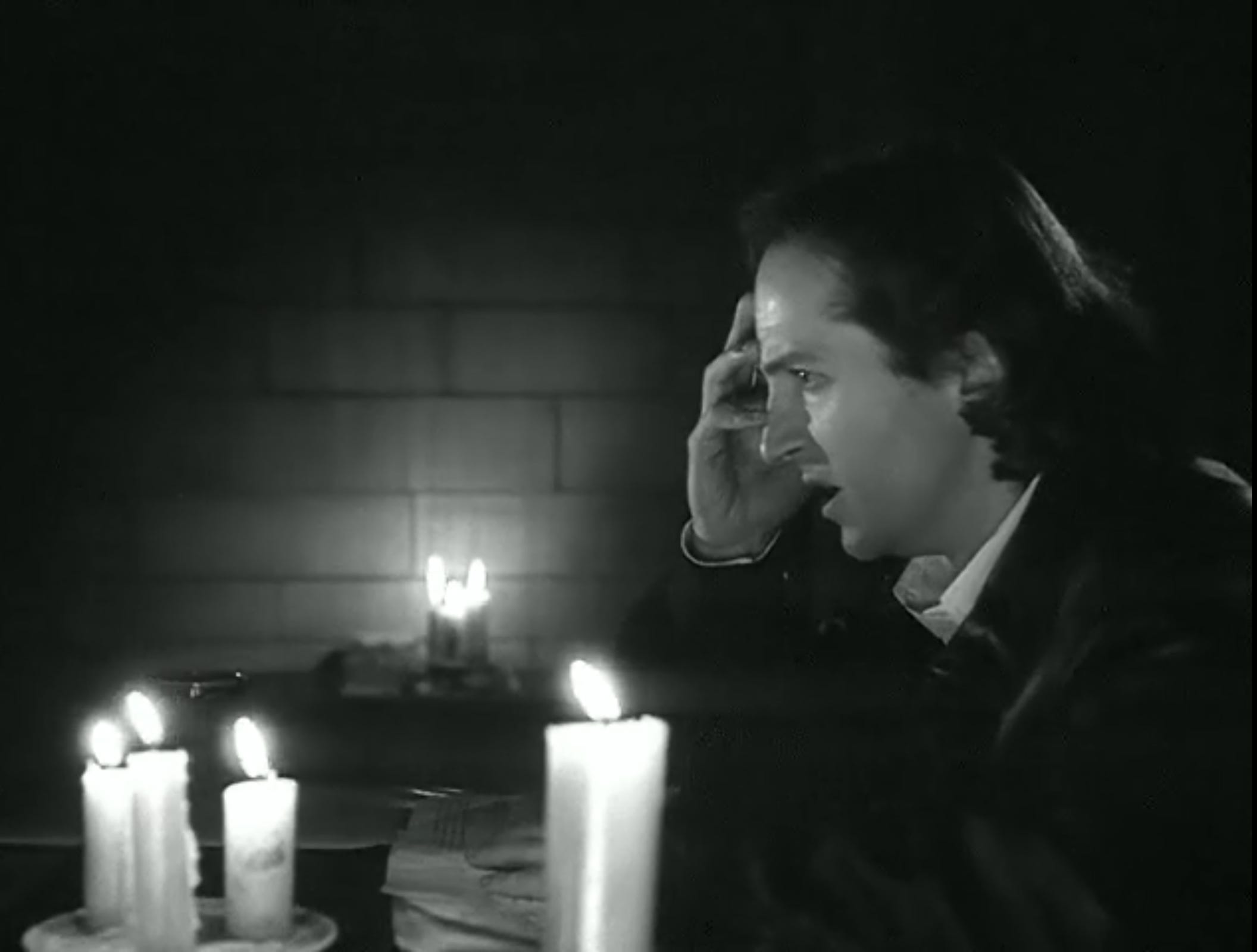

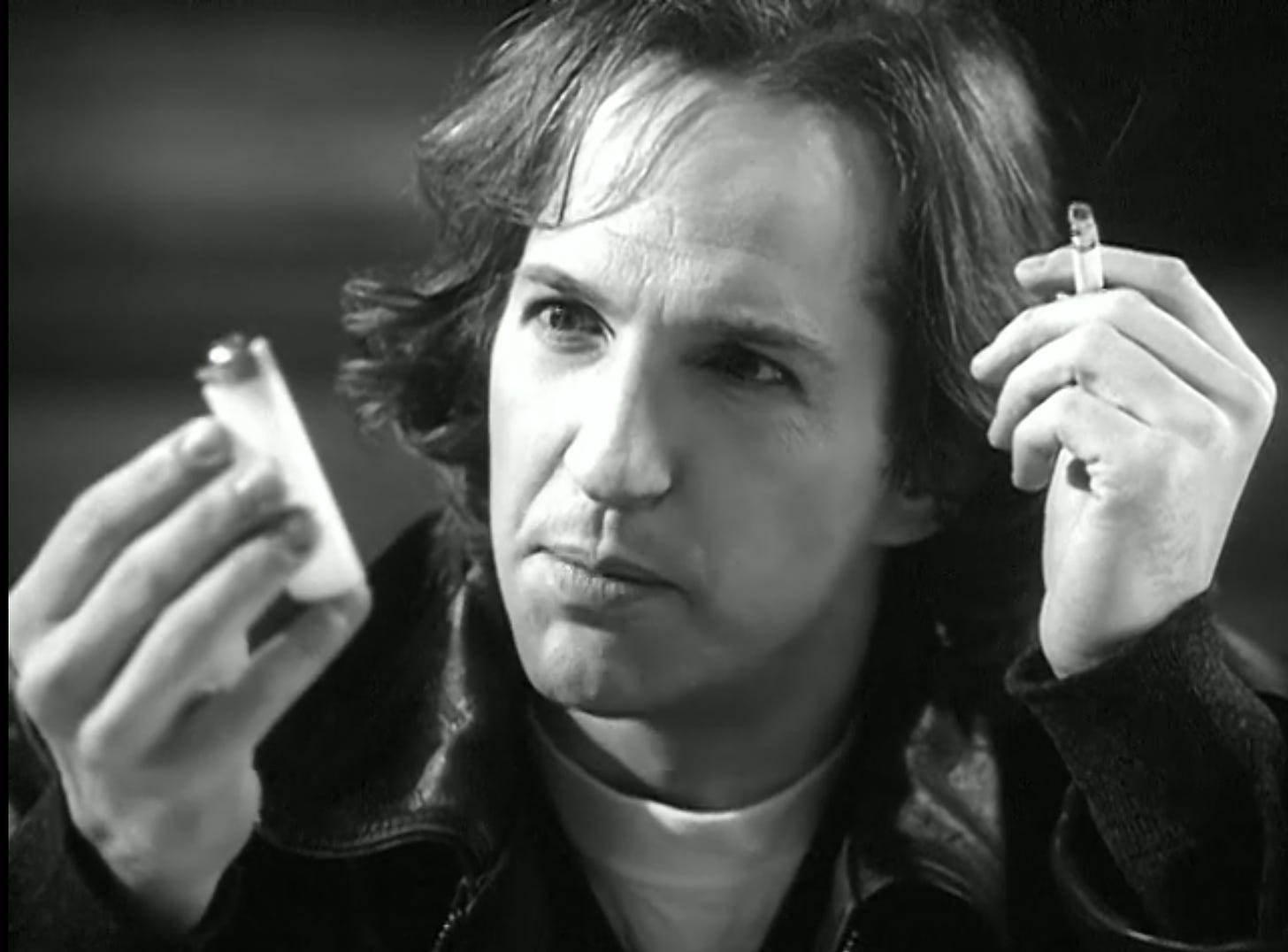

When the film opens, Joe (the brilliant Michael Maloney) is explaining his peculiar brand of seasonal depression. “I was thinking about Christmas,” he says, “the whole thing, you know: the birth of Christ, The Wizard of Oz, family murders.”

This is very familiar: Christmas may feel like a wonderful time of year, but we’re kidding ourselves to think that it isn’t laced with pain, especially this year. As you grow older, you reach a point where you stop associating Christmas with innocent candy-cane joy and start associating it with the Jon-Benet Ramsey murder (I reached that point at age 8.) Once you cease to be a child, the whole Christmas thing just feels a little bit…off. Sinister, even.

Christmas is a time when tensions are high: families treat each other brutally, people get depressed and drink too much, and the presence of the dead looms large over the proceedings. As journeyman actor Terry (played by John Sessions) will point out: “Shakespeare wasn’t stupid, you know. Families: They don’t work out, do they?”

It’s in large part because of this sad fact that we have A Midwinter’s Tale. You see all Joe wants to do is put on Hamlet for Christmas to save an old church in his hometown. That’s it: a passion project. But even passionate people get tired.

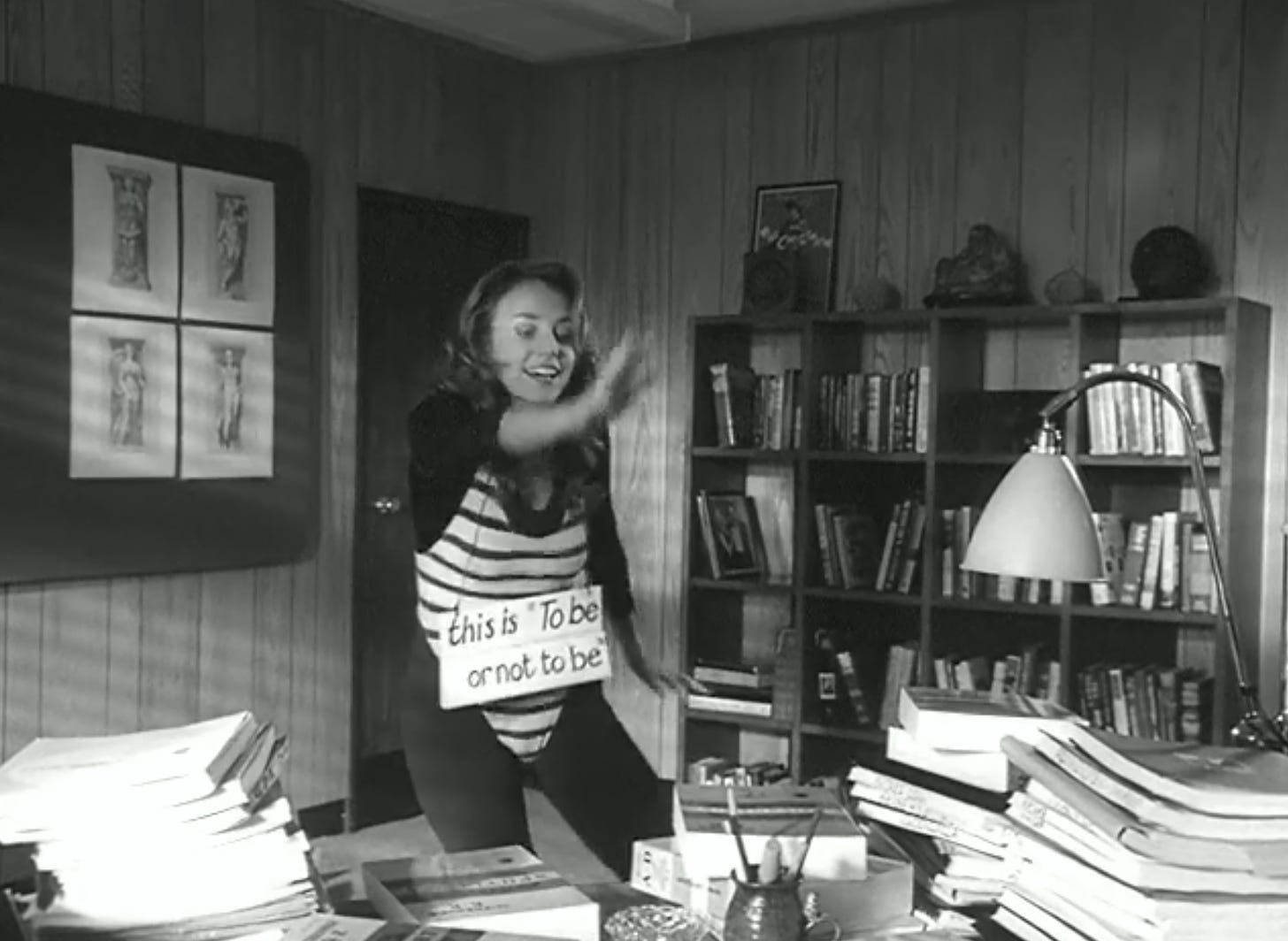

Joe is an actor coming off a year of “spectacular unemployment.” He’s been auditioning all over the place, but nothing’s been coming together. To make matters worse, his nemesis Dylan Judd has just snagged a three-picture deal on a big-budget science fiction film right from under him. Joe is depressed, and very honest about it. He’s sick of being an out-of-work actor. “If everything had gone according to Laurence Olivier,” he says to his agent (Joan Collins,) “I’d have known triumph, disappointment, and married a beautiful woman by now!” So he does the only thing reasonable in the situation: surrounds himself with other out-of-work actors. He puts a casting call in the newspaper asking actors to “enter the world of the gloomy Dane.”

It’s only two weeks before Christmas, and every “real” actor is either already employed or at home with their families. “You can expect a lot of new-age gays looking for a workout,” his agent explains.

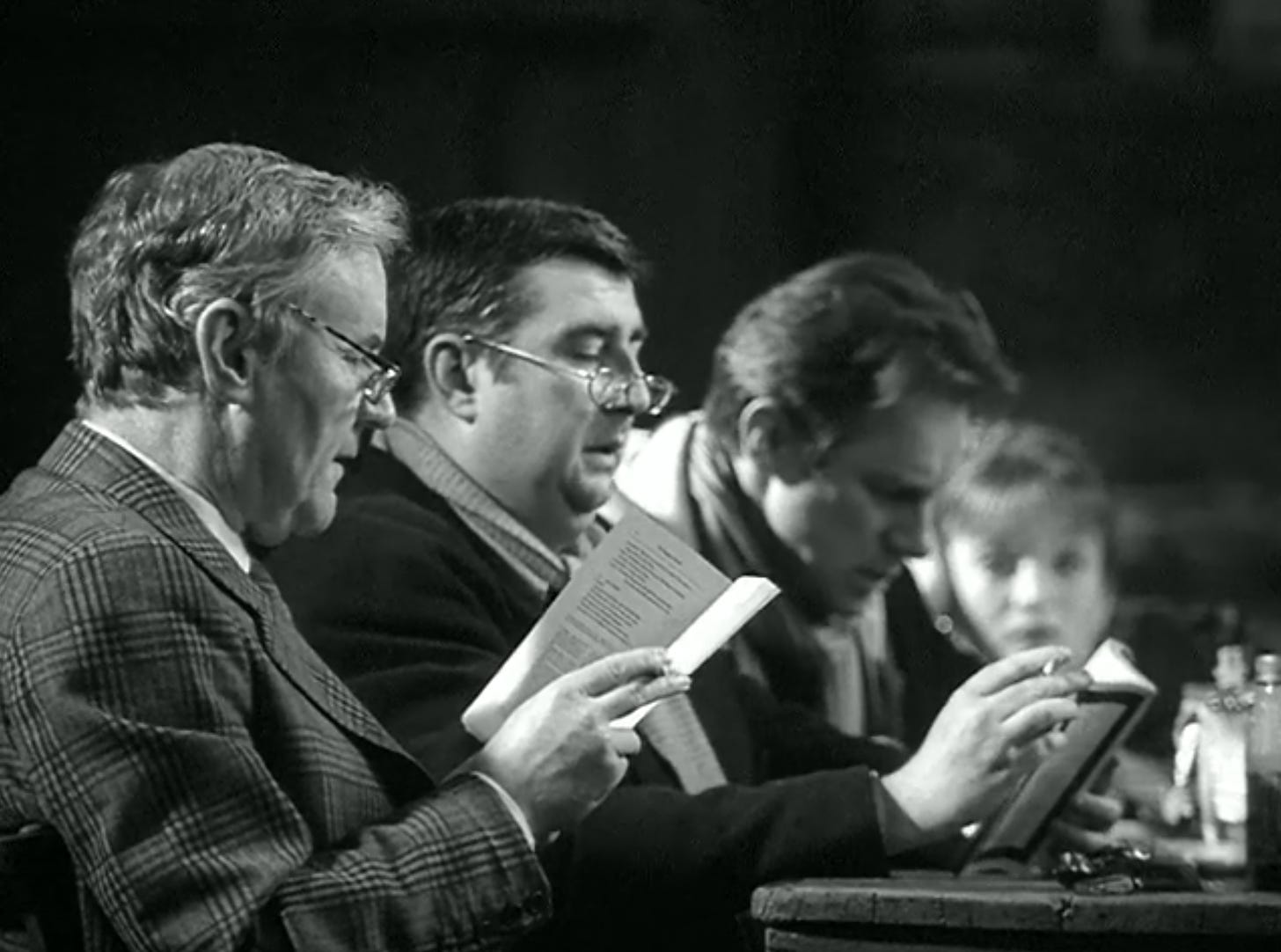

And so it begins: a procession of the world’s worst actors trying to bring Hamlet into the 20th century, via puppetry, modern dance, and regional accents. These lovable freaks will, as in any theater production no matter how lowly, come to comprise Joe’s true family through the run of the play.

There’s Nina, playing Ophelia, who clearly needs glasses but refuses to wear them, causing her to constantly injure herself in small ways. There’s Tom, an insecure, preening actor who loves Hamlet and needs everyone to know it. “Hamlet is Bosnia. Hamlet is this desk,” he says in his audition. “Hamlet is…my grandmother.” More importantly, he can fence. He’s a shoo-in.

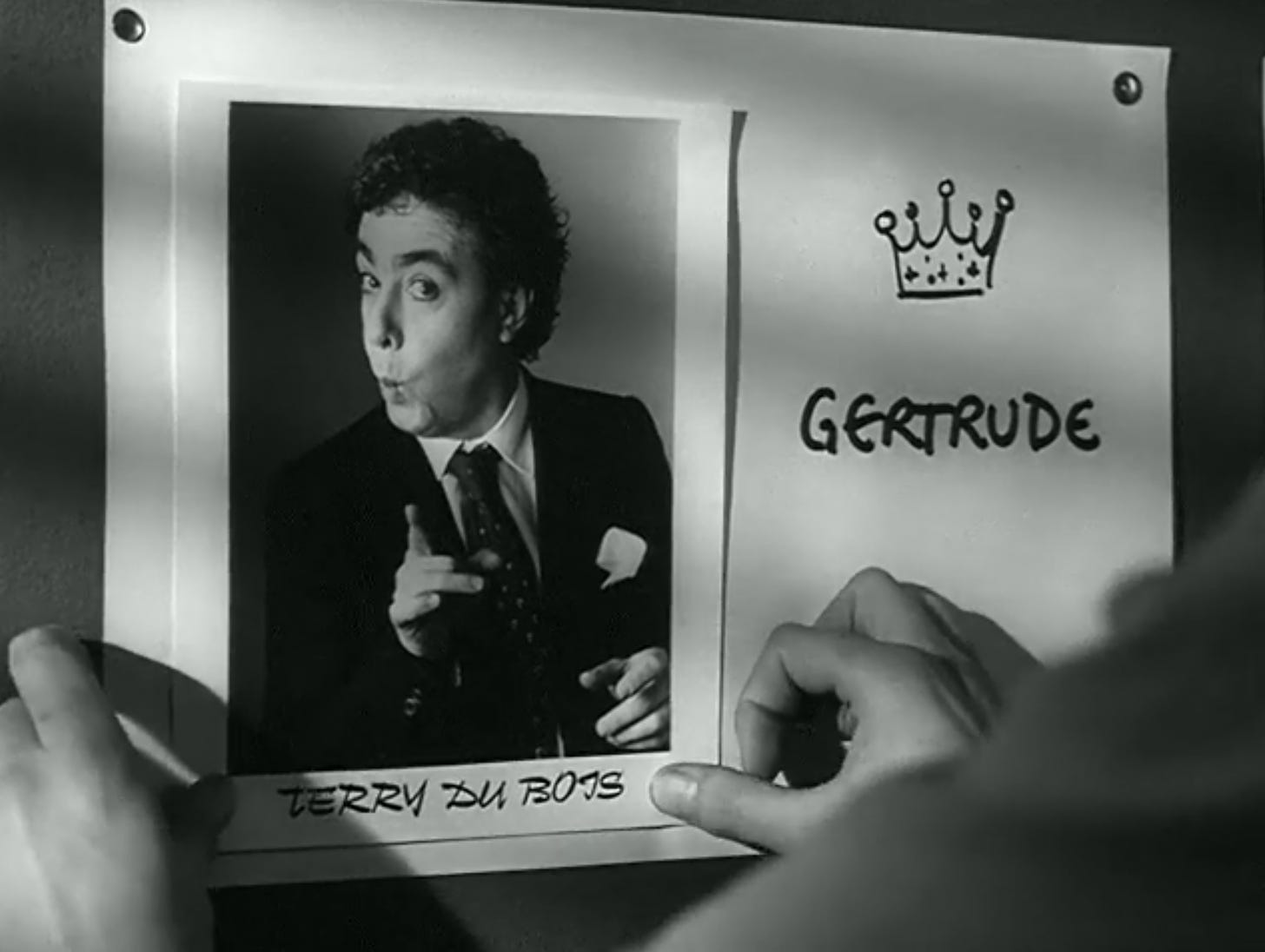

There’s the set designer, Fadge, whose nipples get hard on the evening of every performance (a good sign) and Molly, Joe’s sister, taking care of the logistics. Terry, a gay man who “travels with [his] own tits,” will take the role of “dirty Gertie,” (Queen Gertrude) while Henry, a Henry Irving-obsessed older man (the incredible Richard Briers) who seems Terry’s exact opposite, is cast as Claudius. In time, we will discover the many ways in which every one of these people is wonderful, insecure, thoughtful, and brilliant. But it must be earned.

Part of the joy of meeting all these characters the way we do—in brief glimpses highlighting their particular neuroses—is how it sets us up to be relieved when, against all odds, everyone ends up loving each other ecstatically. The play is a disaster from the start: there’s too little time and too much vision. Everyone’s overacting, and the money isn’t there. They might lose the venue, and there’s a very real threat of playing the show to a completely empty house. People keep saying to Joe, “who wants to see Hamlet on Christmas Eve?” Easy: these people. These misfits, who want to be here, with Shakespeare, in an old, deserted church, more than anywhere else. They’re doing it for themselves as much as for some imagined audience.

“You should be home with your families,” Joe keeps telling the cast after each dismal rehearsal, depressed and embittered, and exhausted.

But there are no families to go home to. From the minute we watch these characters and see them pile into Joe’s huge, broken-down station wagon, we know they’re the family. They were made for each other. These strangers, we know, are going to put aside their insecurity and pain and seasonal depression to create something beautiful and real.

“If we do it well and honestly,” Joe says after the first read-through, “the rest will follow.”

And it does, miraculously and all at once. Nina and Fadge become best friends. Vernon Spatch, a child actor now in his mid-30s playing Polonius, tells the alcoholic, insecure Carnforth that he loves him. Not in a romantic way, but just as a person. “I can’t help it,” he says to the older man. “I just love you.” He goes onto to assure him that the audience will, too. By the end of the play, even Henry and Terry as the Queen and King will come to love each other with the deep, furious passion that comes of sudden intimacy. These people are thrown together, and the miracle is that it works.

But there are other problems. Joe is 33 years old. He has reached his Jesus year, and he just wants something to work out: a job, a relationship, something. He’s been doing the goddamn thing for 11 years, and no dice. He’s putting on Hamlet because it’s the role he needs to play, and he knows he’ll never be cast in it unless he does it himself. What’s more, he’s doing it to save a church in his depressed hometown of Hope, where his sister Molly still lives. We don’t learn about what happened to Joe and Molly’s parents. All we know is they either don’t have a home to go to, or they’re not welcome there.

Joe sees himself, very clearly, as a failure. So when his nemesis Dylan Judd fucks up the three-picture science fiction deal, Joe’s agent gets him in in a pinch and he’s thrilled. The only problem is, he’d have to leave the night of Hamlet’s opening. He’d have to abandon his friends, his new family, and all the work they’ve put into creating the play and saving the church. Joe has to make the hardest choice for any actor to make: do I keep starving and being led by passion, or do I suck it up and get take the corporate job?

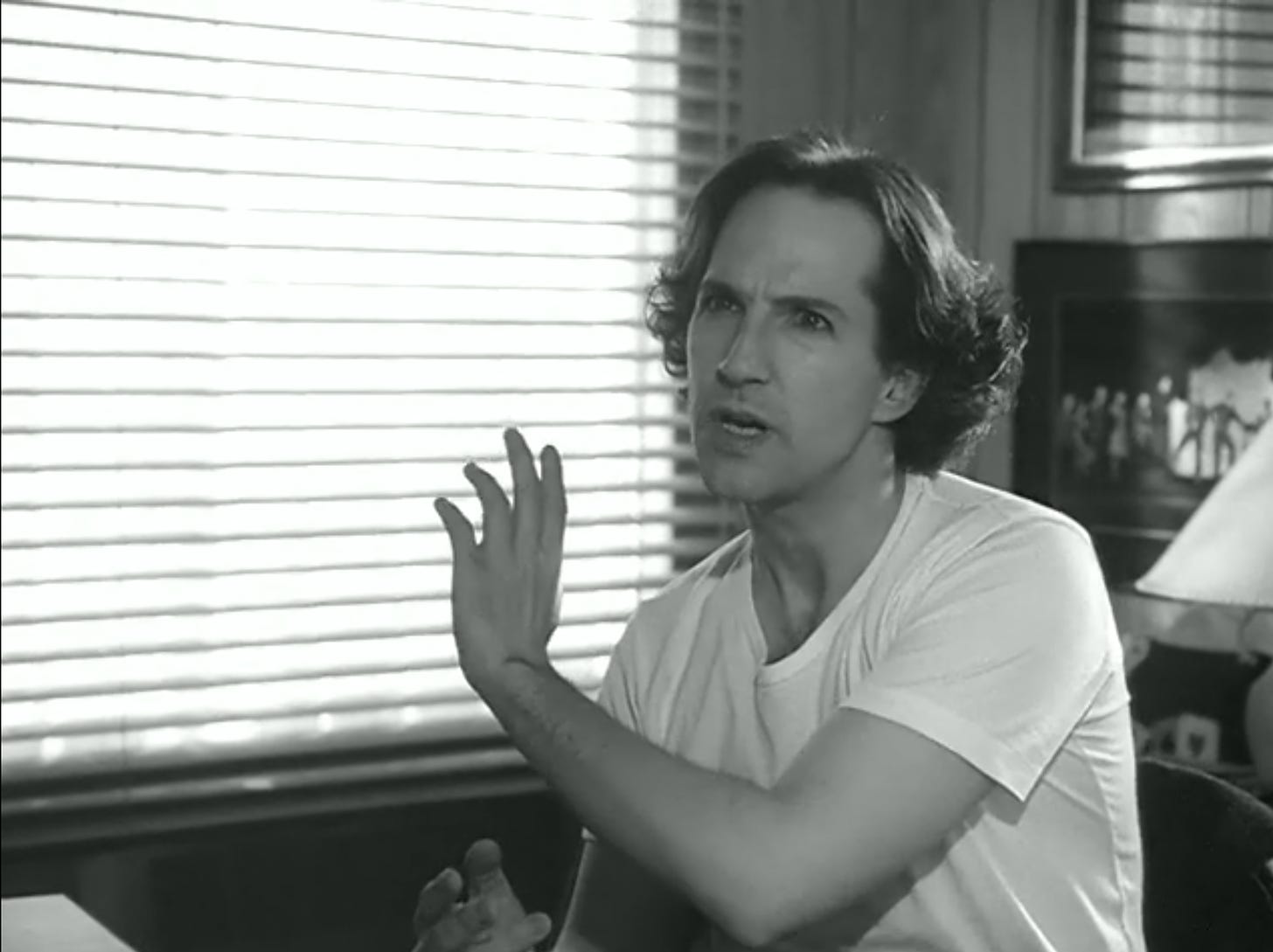

Joe’s depression isn’t trivial or cutesy. The man is clinically, deeply depressed. He has considered suicide, a lot, and he talks about it. During one of the film’s most moving scenes, Joe is addressing his cast after a disastrous dress rehearsal. They only have two days left to shape the show into something resembling Hamlet, and he’s at his wit’s end. “What’s the bloody point?” He screams, taking center stage. “Churches close and theaters close because, finally, people don’t want them.”

The outburst comes as such a shock because Joe, the Joe we’ve seen, at least, has been so gentle with everyone. We’ve seen him take pains with the actors, coaching them one-on-one, being so careful to step around their insecurities even to the point of coddling them (“technically, it’s brilliant,” he says to Tom’s hideous attempt at a Russian accent, “but you don’t sound like a human being.”) Joe has been the rock, and now he’s the one who needs to be coddled.

“As the Yuletide season takes us in its grip,” he says through tears, “I ask myself, what is the point with going on with this miserable, tormented life?”

There’s silence, and then Vernon pipes up. Rachmaninoff. That’s what makes life worth living. And Brief Encounter. The actors try to offer up bits and pieces of the things they find meaningful. For all of them, art is what makes life worth living. And then Joe’s sister Molly speaks up.

“You.” She says. “You’re my brother. You make life worth living. You make my life worth living.”

When I first saw this film as a teenager, I was obsessed with Joe. He was brooding, openly depressed, yet extremely animated and passionate. He was obsessed with Hamlet since age 15, (“It spoke to my heart, and my head,” he says, “and my chief reproductive organ”) and I was obsessed with Hamlet since age 15. Joe wasn’t like any of the boring, un-pretty men I knew in real life. He wears his hair long and flowy, and when he speaks, his eyes light up with fire. He’s the perfect Hamlet, actually: all torment and passion, and desperation.

It’s an uncanny thing when you’ve been watching a film so long that you finally catch up to the age of the main character. I first saw this film at 16. I’m now 34. I’m older than Joe, and I’m finally at a point where I can understand everything that goes into who he is. Why he’s so heartbreaking, and passionate, and finally tired.

For Joe, and for so many queer people who love art, there can be no real backup plan. If you love art, and it’s the only thing you really do love, there can be no backup plan. There can only be desperation, intermingled with that passionate love, creating a kind of hysteria around the work that you do. As ridiculous as it may seem to prioritize work that “feeds the soul,” it is, for so many of us, not a choice. We must feed our souls before doing anything else. Our souls become rich, our pockets remain empty.

Actors, on the face of it, are absurd. They’re preening, ridiculous, self-obsessed, self-conscious, self-hating, and loud. They’re the theater kids who never got enough attention. They’re people whose whole lives are devoted to something that everyone else views as extraordinarily silly, a kind of barely-permissible make-believe for adults. But they are also—as this film very wonderfully points out—some of the noblest, realest, most honest people you’ll ever meet. People who care about words written centuries ago as if they were just breathed onto the page. People who will make themselves ridiculous to prove a point—more often than not somebody else’s point—over and over and over again. They are told that everything they are is wrong, over and over again. That they’re too short, too fat, too skinny, not white enough, not pretty enough, not loud enough, not “it” enough. And they keep coming back for it.

It’s easy to see what teenage me loved about this film, even leaving Joe’s character out of it. These people—all neurotics—are the kind of people I saw myself growing up into. They’re all, I realize now, in their 30s when the film takes place. In a strong sense, I have grown up to become these people. I have become Joe, and I understand the misery of his position more deeply on each subsequent viewing than I ever have before.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox