As you probably know by now, I am a huge fan of silent movies. I am also a huge fan of butts (who isn’t?) So you can imagine my delight when these two interests converge.

You’d think this doesn’t happen often, but you’d be wrong: among the many delights of silent cinema is the fact that, although the Hays Code was in place starting in 1922, it wasn’t exactly…enforced. Nudity wasn’t the biggest deal in the world, especially since back in the day, it was unofficially up to theater owners to censor the films themselves, based on their personal sense of what was too sexy or blasphemous—which meant literally taking out a pair of scissors, removing the few offending frames, and splicing the film back up. That’s the reason so many films once thought lost are often missing certain sequences.

That said, most of the censorship centered on female bodies. Quite famously, Rudolph Valentino films managed to slip a few prolonged undressing scenes in, and nobody complained (okay, some people complained.) In a time when male nudity wasn’t considered sexual—largely due to the erasure of gay male and straight female sexuality—more than a few butts ended up on film. And it’s always a delight to see them.

Related:

This Movie Was Dubbed “the Most Erotic Film of the Silent Era” for This Reason

Charles Farrell’s masculinity was soft, rugged, and unbearably sexy.

One of my favorite instances of this is in the not very good 1927 buddy comedy Two Arabian Knights. The title, a play on the 1001 Arabian Knights, refers to the two (white) leads, because this movie is insanely racist (Mary Astor plays a Middle Eastern woman—oy.) The leads in question—William Boyd and Louis Wolheim—play American POWs who end up in an unspecified part of the Middle East after getting captured. Now I know what you’re thinking: why are American WWI soldiers in the Middle East? Wasn’t that famously a war fought on the…you know…Western Front? Listen, I don’t know. These people wanted to make a movie set in some kind of fantastical Arabian paradise, and they did, because…racism.

But all that is somewhat beside the point: because there’s one scene in this movie where these two men are being processed into what appears to be a POW camp or army barracks, and it’s here that their friendship first blossoms. It’s also here that the movie gives us a heaping serving of background man butt.

For a full five minutes, we’re watching nude men go by in the background, the very tippity top of their asses exposed. With no explanation, no commentary, and barely even a nod to what’s happening onscreen. I mean, I suppose we’re supposed to be looking at the foreground. And yet…how could we? It’s a veritable tush parade!

When I first saw this at age 18, I thought it was extraordinarily funny. Having a conveyer belt of top butt running behind a scene in which our two leads are discovering the power of male friendship during wartime…it simply felt too cheeky (pardon the pun) to be accidental. Somebody, somewhere, decided that this movie was going to have a lot of butts in it, and that person manifested their dream on camera.

But as always, there’s something deeper going on here: Two Arabian Knights was by no means an original concept by 1927. The wartime buddy comedy had been well established long before. After the 1926 smash hit What Price Glory, everybody saw the huge box office possibilities for vaguely homoerotic comedies about wartime besties. That same year, all-but-out gay actor William Haines starred in a similar film called Tell It to the Marines, and John Gilbert starred opposite a young Greta Garbo in Flesh and the Devil, a story about two military buddies whose extremely queer friendship is torn apart by—you guessed it—a sexy lady. Basically, people loved this sh*t. They ate it right up, and there were plenty more of these comedies to follow.

In 1927, we got the WWI buddy comedy Wings, a film that not only featured a platonic love story between two men, but one of American cinema’s first-ever depictions of lesbians enjoying an almost-kiss in a Parisian bar.

The film became the first-ever Best Picture award winner at the inaugural Oscars.

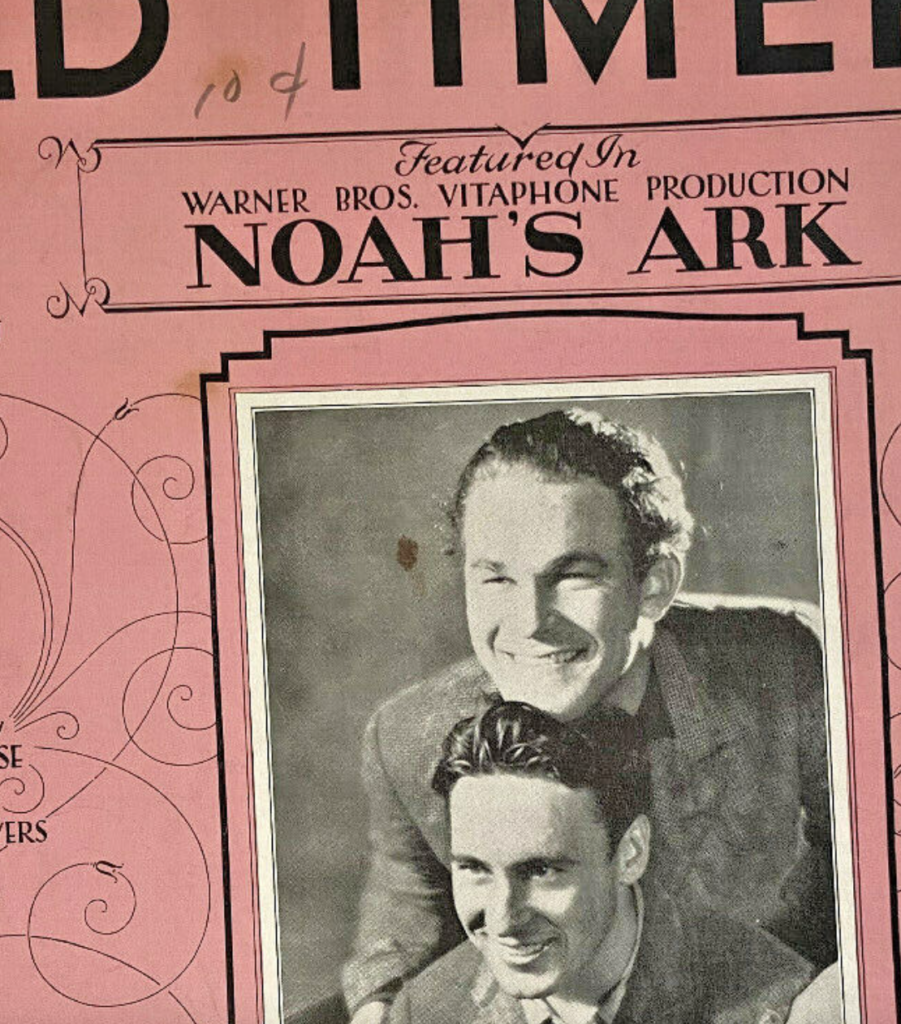

In 1928, the WB epic Noah’s Ark would feature a similarly homoerotic plot centered around two World War I vets who enjoy a sexually-charged reunion. It’s no surprise that the two leads—George O’Brien and a man known simply as Guinn “Big Boy” Williams—had far more chemistry than the straight romantic coupling of O’Brien and Dolores Costello. This was par for the course: during WWI, doughboys were encouraged to develop strong bonds with the men they fought alongside. This led to the creation of several sentimental ballads about male friendship, including 1922’s “My Buddy,” which played a large role in the parts of Wings‘ sound score. The lyrics (“nights are long since you went away/I think about you all through the day, my buddy”) aren’t just about losing a friend: they’re about losing a piece of your heart.

Silent movie actor George O’Brien, 1925

by u/Sea-Bluegreen in VintageLadyBoners

That’s why for Noah’s Ark, a copycat song was commissioned for the soldiers’ grand reunion. Titled “Old Timer,” the song is a similar ode to male friendship, and maybe something more. I mean you tell me if you think I’m stretching it.

The song plays at a very specific moment: after a battle during which the two friends thought they’d lost each other forever, they’re reunited in an army camp. They see each other from across the room:

Visible tears form in their eyes.

They embrace while “Old Timer” plays…

They kiss…

And hold hands.

And if that wasn’t gay enough for you, the two men ended up on the sheet music for “Old Timer,” just looking like guys being pals. Nothing to see here!

Now look, I’m not saying that every wartime buddy comedy is gay by proxy. But there was a certain something in the pre-code air when they were making these films. By the late 20s, a lot of young men remembered fighting in the first World War: they lost their health, their jobs, and sometimes, the male friendships that made life worth living. It’s no wonder that these films hit on something accidentally homoerotic. And they would keep on doing so throughout the 20th century, even after the code was firmly in place.

Some comments I found while searching for the lyrics of “My Buddy” hit especially hard in this context. “On rare occasion [sic] a bond will develop between friends based on shared and difficult times.” one commenter wrote. “The bond is as strong as that between brothers. This song is about such a bond.”

“My late parents used to sing this,” another wrote. “My father was a world [war] one army officer. Both said it was a popular song during World War One era. Dad said it referred to friends who died in combat. Mother said it referred to sweethearts who were lost during this war. It is a song of loss, yearning.”

It is a song of yearning. And these films, too, chose yearning as their subject. That yearning was disguised as comedy, but looking at them more closely, we can see what they’re really about. They’re about love between men, in whatever form it takes. These films and songs were a way to appreciate and express a need for those bonds, whether they were romantic or not.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox