If the phrase “Will Smith twink” is of all at interest to you, I have a very weird movie to introduce you to. But first, let’s take a journey through time…

The year was 1990, and John Guare’s hit play “Six Degrees of Separation” was scooping up awards during its Broadway run. The play was peak neo-liberal theater: a piece that seemed to question the complacency of liberal white people while still, ultimately, letting them off the hook. And it was based on a true story: in the 1980s, friends of Guare’s told him a strange story. One night, a young Black queer man, David Hampton, had come to the couples’ apartment asking for help after being robbed. He claimed to be a Harvard student who knew their kids there. He also stated that he was Sidney Poitier’s son. He stayed the night, and in the morning, the couple discovered him in bed with a friend, a man the couple assumed was a sex worker. They were outraged: they told their story to their friends, and soon found out they weren’t the only people who knew David Hampton as the fake son of Sidney Poitier (who only had daughters.) He’d been doing this for a while, and he’d been doing it well. David Hampton took code-switching to the level of art: he used his knowledge of rich white liberal idiots to gain entry into their worlds, and con them out of small amounts of money. It was a juicy story that Guare couldn’t put out of his mind, so he dramatized it.

A movie adaptation was imminent.

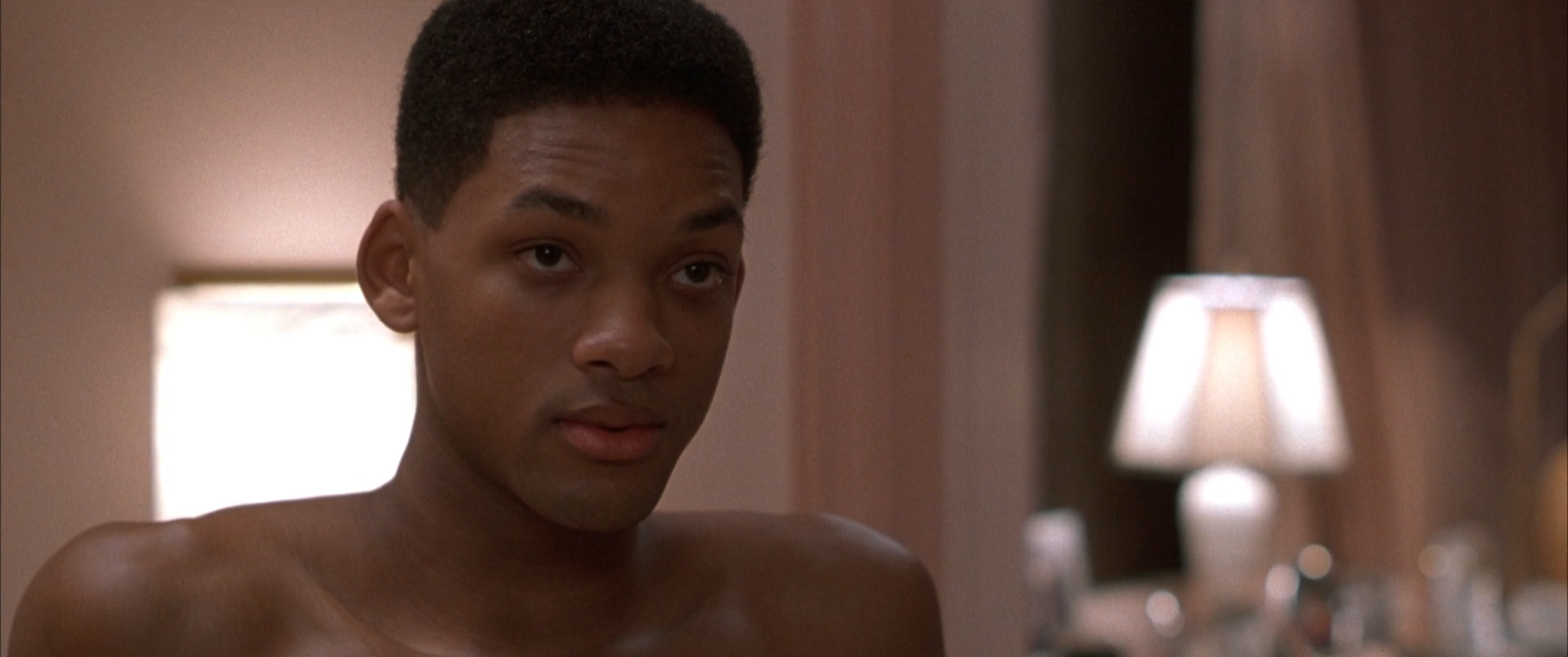

Fred Schepisi’s 1993 film wisely cast a young, extremely hot Will Smith in the role of Paul, the Hampton analog. We meet him after the WASPy Kittredges, Flan and Ouisa (Donald Sutherland and Stockard Channing) tell the story of their one-night run-in with Paul to friends, a telling peppered with flashbacks. Flan and Ouisa, both art dealers, are on the verge of making a huge sale to a visiting buyer from South Africa (Ian McKellan.) When Paul knocks on the door, he’s bleeding. The couple take him into the kitchen, strip him down, and try to treat his wound.

From the start, there’s a lot going on with Paul. First of all, he’s oozing with charm, especially as Smith plays him. He talks with a Patrician accent and gives out personal details about the couples’ kids at Harvard. He waxes lyrical about his thesis, a take on the inherent violence of “Catcher in the Rye.” And the couple end up falling totally in love with him: there’s a clear sexual element to this encounter that the movie accentuates. Not only does the middle-aged couple seem equally titillated and impressed by Paul, they quite transparently want to f*ck him. I mean—he’s Will Smith, who wouldn’t? After Paul takes off his shirt, we can see Ian McKellan’s character standing in the doorway staring hungrily at his body.

But there’s more going on than just attraction. To gain the couples’ trust, Paul paints himself as an almost impossible portrait of respectability, something to rival Poitier himself in his early roles. Paul, like anyone in the position of “other” who finds themselves in a climate where they feel they must present themselves as perfect, stainless, and subservient, does everything he can to make the couple feel at ease, taken care of, and flattered. And like most white couples, Ouisa and Flan totally eat it up. To them, Paul represents the triumph of neoliberalism. They see him as a product of a society that has magically overcome racism without white people having had to change their views, interrogate their own racism, or give up any of their comforts. After all, he makes it so easy! He cooks for them! He discusses Kandinsky with them!

But that’s exactly what code-switching is: putting people at ease so they don’t kill you.

Related:

Black Men Are Allowed Complexity: Exploring Black Masculinity in Film and Television

When will Black men be allowed to express variations of masculinity not yet seen onscreen?

The Kittredges love having Paul around, and they invite him to stay the night. But in the morning, when they discover Paul getting it on with a hot stud, they freak out. Paul being both Black and queer seems suddenly just too much for the bourgeois couple. Paul runs away, only to return at the tail end of the story, when he’s arrested at the hands of the Kittredges. Because despite its attempt at commentary on class and race, this is a play written firmly from—and steeped in—a white point of view. It views Paul as a liar, and an expendable one, even if it tries weakly to achieve some kind of empathy for him in the end.

Six Degrees of Separation is not a great movie: but it does achieve an interesting meta effect through Will Smith’s casting. As a Black actor in the process of becoming a mega box office star in the early 90s, Smith drew frequent comparisons to Sidney Poitier, a Hollywood actor who was also often placed in respectability roles in films about race primarily aimed at white people. Just as Poitier had to play such roles, Smith had to carve his own path as a leading man by walking the same road. But the problem with respectability politics is that they drastically limit the personhood of those who fall—or are forced—into that specific trap.

“Onscreen,” writes INTO author Anwar Uhuru, “we’re finally starting to be asked to grapple with the ways that Black men deal with intimacy, care, and what it means to be vulnerable.” But in 1993, respectability politics were still the order of the day, and even a huge star like Will Smith had to present himself a certain way in order to succeed in Hollywood. And considering the egregious, racist discourse around last year’s Oscar’s slap, it’s pretty clear that he still has to. God forbid Smith express a moment of completely human anger after someone insult his wife: God forbid he let the mask slip for just a second. It’s all too clear that code-switching and engaging in respectability politics is still often required of Black men and women, even if they happen to be hugely successful moguls.

And that’s really what Six Degrees of Separation is about, or at least what it tries to be about: the trap of respectability. Today, we’re constantly calling for nuanced depictions of queer villains in cinema. Smith’s character in this film is far from a villain, but he’s also not a pure victim. He’s a complex queer character to whom the film should rightly belong. It should be about him, not the people he cons. But the film—and the play—rob him of that. The story, in the end, abandons its greatest character, and that’s a huge shame.

Stories from this era—tales ostensibly about race written by white authors—are famous for throwing their characters of color under the bus in order to preserve the comfort of their white characters. As an artifact from the recent past, Six Degrees of Separation remains a fascinating, flawed study in the way that whiteness tends to swallow everything whole and then blame everyone else for that exact devastation.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox