When she was a teenager, Ry Russo-Young appeared in Meema Spadola’s documentary Our House, about children across the US with queer parents. After showing in theaters in 2000, the film aired on PBS in 2004, just as queer marriage was starting to be declared legal in some states. The backlash, too, was just beginning. So—perhaps understandably—the families in Our House serve as propaganda: the parents, loving, and the kids, cute, articulate, and seemingly well-adjusted. But Russo-Young, who grew up to be a director herself, has now made a spiritual sequel to the first film: the docuseries Nuclear Family, about her biological father, Tom Steel, a gay lawyer who sued her lesbian parents, Robin Young and Sandy Russo, for shared custody when she was a child.

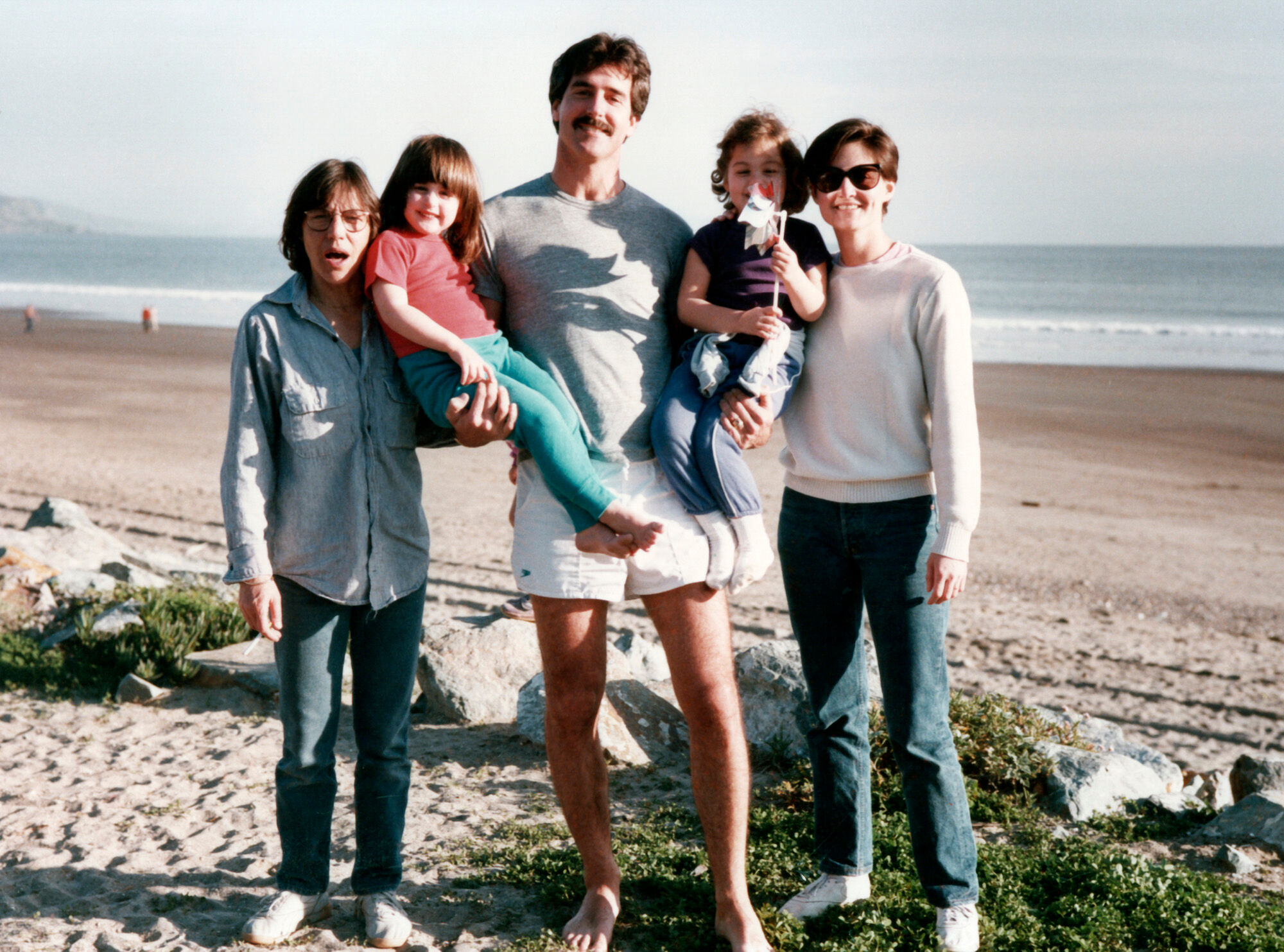

The first episode is my favorite. It sets up the conflict, first showing the extreme homophobia of the time, then diving deeper into the pockets of the lesbian feminist community, much of which was, at the time, putting out DIY pink, hokily-illustrated pamphlets of women inseminating themselves¹. Russo-Young also walks us through the process of how sperm donors were found, and how families explained to preschool-aged kids why they didn’t have a Dad like other kids did. Russo had grown up not knowing her biological father and was determined not to keep her children, Ry and her sister Cade, in the dark. The family ended up spending vacations with Tom and his partner Dr. Milton Estes, and we see plenty of happy home videos (often shot by Estes) and smiling photos of them all together.

Russo and Young had always been insistent that their family be recognized as queer and also be traditional–or as traditional as two queer Moms living with their kids in a loft in the West Village in the late 20th century could be. Young even stayed home to take care of the children. If Steel was legally declared Ry’s father, “It wouldn’t be the family we wanted, we planned, we struggled for,” Russo says.

Russo and Young had always been insistent that their family be recognized as queer and also be traditional–or as traditional as two queer Moms living with their kids in the late 20th century could be.

The film makes clear that courts would recognize only two parents, so if Tom was declared Ry’s father, Russo would be a permanent, legal stranger to the daughter she had raised. But the two women dictating—as straight parents do—what Tom could and could not do with Ry, became intolerable to him and to Milton. The family videos became evidence that Tom was Ry’s Dad both socially and biologically. Smiling photos submitted to the court were cropped so Cade, who had no biological connection to Tom, was cut out.

Even back then a sperm donor (sperm banks had been around since the 1960s) to a straight couple wouldn’t have sued for custody. Some queer people around that time used homophobic laws and judges to cut ex-partners off from their children. The battle between Russo-Young’s parents and her biological father is emblematic of the problems between queer men and women in the community then and now: some of us in activist groups were surprised when the men in those groups ended up turning on us, for their own selfish, often misogynistic, reasons.

The custody dispute dragged on for four years—an eternity for a child. Tom tries to justify his behavior in a video he sends to Ry. saying: “There’s always two sides to any story.” Family friend Cris Arguedas, who initially introduced Young and Russo to Tom Steel and ended up testifying on Tom’s behalf, says hollowly, from behind a lawyer’s tight smile, that: “We were creating a new world of gay liberation. Your parents were part of that.”

Some queer people around that time used homophobic laws and judges to cut ex-partners off from their children.

As Russo found when she phoned the lawyer who represented Tom, these people—including queer friends like Arguedas and pillars of the queer community like Estes and Steel—in the end considered her family kind of a half-assed, pretend one that didn’t warrant the rights straight families had, though all these people had previously played along as if they had believed otherwise. Even now, Arguedas seems surprised Russo and Young cut her completely out of their lives forever, even though any straight parent threatened with the loss of a child would do the same.

Russo-Young focuses on her feelings about Tom, which have mellowed into ambiguity since she last spoke to him as a teen. In that conversation, she told Tom she would never forgive what he had done. Personally, I would have preferred, instead of repeat scenes of Russo-Young’s tears, questions directed at her sister Cade, about her perspective as a second-generation queer parent. These questions—not only concerning Tom’s rejection of her as a child, but the precarity of their mothers’ position too, especially compared with that of queer parents today—would have opened the film up in a more expansive way.

The last episode concludes with Russo-Young and her husband going to the hospital where she gives birth to their second child. It’s an important moment in her own life, but an anticlimax for the series. In the final scenes, the audience sees—as we didn’t get to in childhood videos of Ry, where she favors her mother—that as an adult her eyes and nose are unmistakably Tom’s. But Russo is the one holding the new baby.♦

The finale of “Nuclear Family airs on HBO on Sunday, Oct. 10

¹Susie Bright, in one of her early books, recounts an insemination party that took place then, each woman taking a turn squeezing the turkey baster.

Don't forget to share:

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox