I was no more than twenty minutes into Mitchell Leisen’s Death Takes a Holiday— a film I hadn’t seen in about 10 years—when I realized it was about being trans.

I have a podcast exclusively dedicated to this kind of thing: finding transness where most people wouldn’t see any at all. I’ve been finding transness everywhere I looked, ever since I knew how and where to look for it, because it’s what I’ve had to do. When there aren’t any stories about you, you have to make them about you. That’s what I did throughout my childhood, through sheer force of will. Now, as an adult, it comes more easily. Sometimes it just falls into my lap.

The point is, I’ve trained my brain to do this, and on the way, I’ve discovered certain subgenres that invite a gender-fluid or gender-weird reading. For instance: movies about the dead or dying. Movies about the liminal state in between death and life (Beetlejuice, Topper, Soul, Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Defending Your Life.) But in particular, movies where Death is personified.

I’ve always liked the idea of the Grim Reaper-as-character. There’s a lot of room to play there. For instance: Who the fuck is he? How’d he get the gig? Would he think about things other than death? Is death like a vocation for him, something you pick up at 8am and put down at 5pm? Or does it follow him everywhere? What’s Death’s gender? What does Death look like? Does it have a body?

In media where Death must walk on earth with the living, there is an odd consistency to his characterization. In 1939’s On Borrowed Time, death is Mr. Brink, a patient, gentlemanly presence. In one “Twilight Zone” episode, he’s “Mr. Death,” cool and collected in a suit. In another, Death is Robert Redford, charming and mischievous, more a pan-like imp than a grim reaper.

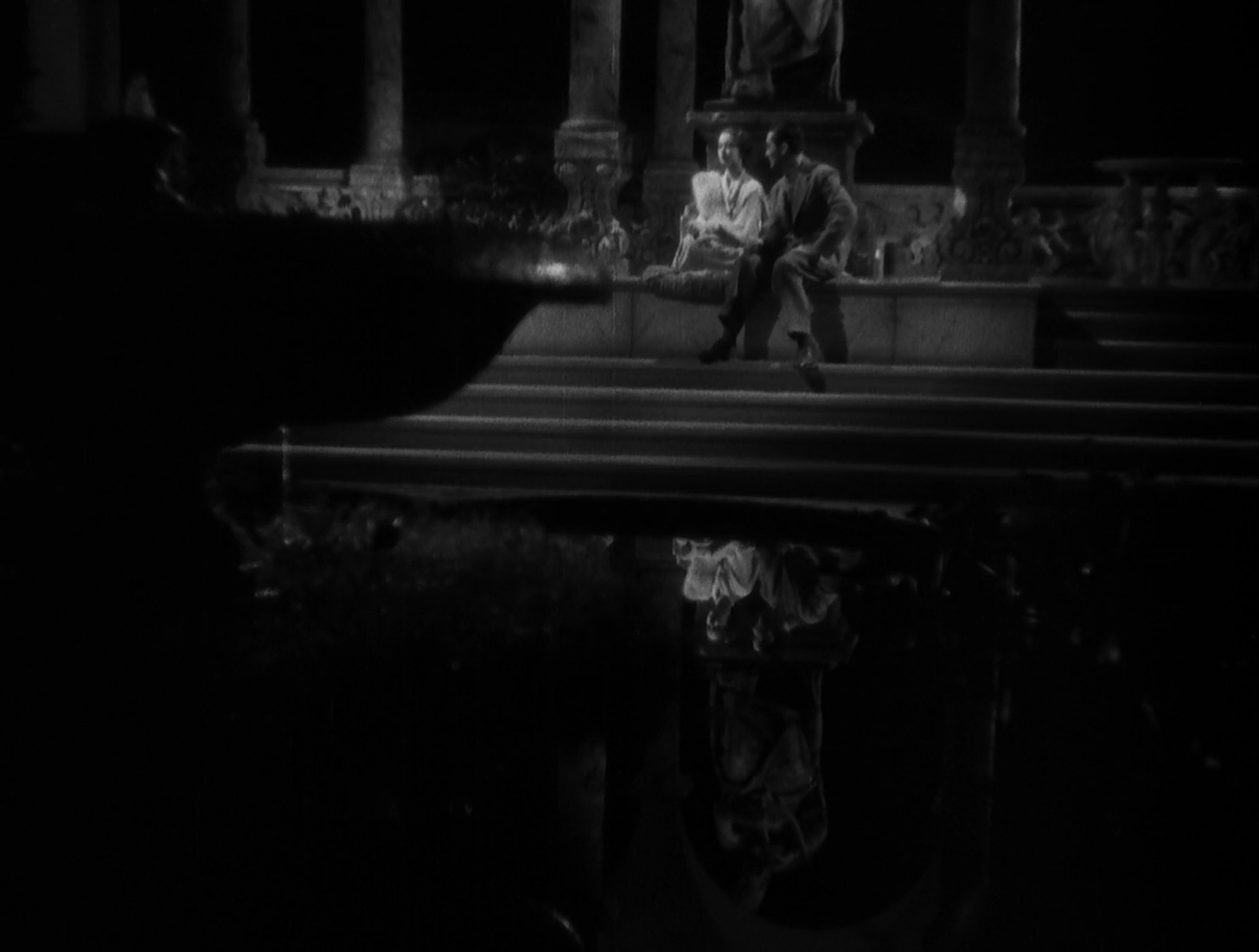

In Death Takes a Holiday, Death is likewise a gentleman. He has stopped at a random Duke’s guest-laden Italian villa during a weekend celebration. He appears to us first in a see-through cloak and announces himself as Death. He explains his intentions—to find out why humans are so afraid of him—and tells his host that he will stay among them as a guest for three days, and in that time, he will hopefully learn what’s so great about life that everybody freaks out when death comes to claim them.

To do this, he must transform. He must take a body to live in for the three days, and he chooses the form of Prince Sirki, a royal who was invited for the weekend, but who conveniently died en route. Death instructs the Duke to tell no one that Prince Sirki is actually Death personified, on pain of…well, death.

Death transforms into Sirki and is at once introduced to the Duke’s close circle of extremely rich friends, to their delight. After all, he’s Fredric March. He’s hot, he’s charming, and he’s one of the only actors that can really pull off some of the absolute clunkers that compose the script. Exchanges like: “You are Death!” “HA!” and lines like “what could terror mean to me, who have nothing to fear!” He describes himself as a “vagabond of space” who is “weary of being misunderstood.” He is not of this world, but not really of any other world, either. He lives in the in-between. And when he decides to take a body, it comes with a few unexpected consequences.

Desire is the main one. Death/Sirki pretty soon figures out that the pleasure of life is to be found in pleasure itself. He tries hitting on all the women at the Duke’s large estate, but it keeps falling through until he starts talking to Grazia, the youngest member of this weird rich-person cohort. Grazia is her own kind of goth weirdo. Before we even had a chance to meet Death, she was talking about his arrival in a starry, far-off way. She told her fiancee, in an early scene, to leave her alone so she could simply sit and think about death. She and Sirki are a match made in heaven. But she doesn’t know his “secret” yet, and he’s caught up in the pain and confusion of having a body. “I have been caught in this web of flesh,” he explains. “I thought I could put it on and take it off like a skin.”

But he can’t. And that’s where the film gets interesting. It starts to ask questions that even theology doesn’t dare ask. Like: what’s the difference between taking a human body on a test drive and becoming human? What about Jesus? When he spent his time on earth, was he human by virtue of having a body? Or was he a divinity cosplaying as human for a while?

Sirki’s questions keep coming. How do I feel good in a body? How do I get close to people without letting them in on my secret?

Meanwhile, nobody’s dying. Death is off-duty, so all these freak accidents keep happening with no fatalities to follow. We’re told that during some ongoing war, the guns on both sides were unable to fire. Nobody thinks anything of it. But Death knows his place, and knows the role he plays. He knows he’s the flipside to all this— the wealth and beauty and chilly interiors of his rich friends and their world. He knows a price has to be paid for all of it, and he is that price. He just wishes he could make these humans think a little differently about Death. Even though he knows he can’t.

By the end, Sirki’s three days are up and he has to return to doing his job. He’s been exposed by this point, and everyone knows who he is, except for Grazia, who he’s fallen in love with. The conversation now turns to disclosure. “You have to tell her that you’re Death,” everyone says. “It’s only fair.” But Death himself isn’t so sure. Why fuck up something beautiful when you don’t have to? Why not just vanish into the night? Why disclose anything at all?

At one point, while flirting with a woman who’s clearly interested in him, Death/Sirki explains: “you will take one step toward me and know my secret and lose courage.” I don’t think a truer phrase has ever been written about the problems of dating while trans. About the problems of trying to engage with the world when the world is deathly afraid of you. About trying to change the conversation around what and who you are while being surrounded by people who actively fear you, because they don’t understand.

Death—and transness—are misunderstood here not for the first time, but in one of the most interesting ways I’ve seen. It’s all here, in this 1934 movie: conversations about disclosure, the feeling of physical unease in public, the distrust and self-imposed distance, the fear of having someone fall out of love with you when they learn “who you really are.” The futile attempts to remove the fear that comes in at the back of people’s eyes when you tell them what you are. It’s all here, and it’s great.

The best part? Grazia goes with him at the end. He tells her who he is, and she basically says, “yeah duh I knew all along” and follows him into the afterlife. It’s the thing he wanted to do—to take her with him and make her his Persephone—and the thing all her friends and family members kept fighting against. Everyone keeps telling Death that he needs to sacrifice his love for Grazia because it’s the right thing to do. “You don’t feel real pain,” they keep telling him, “you’re beyond suffering.” And even though he tries to explain to them that that couldn’t be further from the truth, they can only see his intervention in their lives as a threat. “It’s my pain against yours,” he says.

It is a threat: and a seduction. But Grazia, for her part, has never wanted to be part of this world. Not only does she accept Death, she understands that a life with him is more vibrant than anything on Earth. So they go off together into the great unknown.

Death Takes a Holiday is a curious movie in every sense of the word. It’s weird, bizarre even. But as a film, it has a curiosity about the world beyond that’s grounded not in religious dogma, but in something entirely new. Call it empathy with the Devil. It places Death in the same position later films would place queer people: as misunderstood, charming, but ultimately unknowable entities whose relationship to love can only end in pain or greater-good sacrifice.

Which is why a happy ending of this kind—so unexpected and oddly earned—is so beautiful to see. Earlier on, we heard a piece of off-screen dialogue from Sirki by way of the Baron Cesarea (played by the great Henry Travers.) “He asked me, ‘has it ever occurred to you that death may be simpler than life, and infinitely more kind.’”

Of course it didn’t occur to these people. They belong to the world of light and wealth and disclosure. They can’t think of Death as any form of kindness, because they haven’t suffered.

But Death can be a welcome thing for people in pain, people who are depressed, people who are just tired and done and over it. But what I like best is that you don’t ever actually see where they’re headed. At the end of On Borrowed Time, Mr. Brink finally gets his wish and claims a young boy and his grandfather. The three of them then find their way to a suburban paradise, complete with barking dog and picket fence. It’s a very 1939 version of Heaven.

Here, we’re not invited to go beyond “where the Woodbine twineth.” And we shouldn’t be. The film has done enough to create a kind of exciting mystery about the world beyond. It’s excited about the afterlife in a way that most films aren’t. And that might be a strange, roundabout path toward empathy, but it’s a start.♦

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated

Read More in Entertainment

The Latest on INTO

Subscribe to get a twice-weekly dose of queer news, updates, and insights from the INTO team.

in Your Inbox